In China, Red Party Is Shade of Its Old Self

- Share via

BEIJING — The Shanghai stockbroker said he joined the Chinese Communist Party to get a head start. “If you want a promotion,” the 26-year-old university graduate argued, “you need to be a party member. There are lots of benefits--salary, housing, chances to go abroad.”

A Beijing furniture company owner, 29, said he enlisted in the party to get a quick jump in business and for protection in case something goes awry. “If you get caught doing something wrong,” he said, “the worst thing that can happen to you is that they will kick you out of the party.”

A young Chinese executive with a German company said he was recruited into the party as an outstanding young collegian. “The party got all the best students,” the executive, now 26, explained over lunch in a luxury hotel where his company leases him an apartment. For him, party membership means belonging to an elite club of present and future Chinese leaders.

There is not a lot of revolutionary fervor left here in the land of the Long March. There is almost nothing more said about serving the masses and learning from the workers and peasants. But that does not mean that the country’s dominant political institution, the 58-million-strong Chinese Communist Party, is on its last legs.

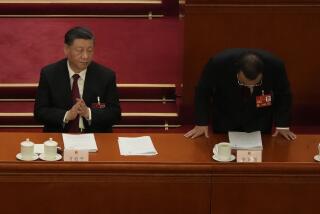

In fact, today’s Chinese Communist Party--which opens its 15th National Party Congress here today at the Great Hall of the People--is the largest, youngest and best-educated party in almost 50 years of Communist rule. The party ranks have grown by almost 10% in just five years. More than 22% of its members are younger than 35.

What has changed, though, almost completely is the once-heavy emphasis on Marxist-Leninist-Maoist dogma. The party no longer oversells its role as “vanguard of the proletariat.” Instead, it emphasizes its elitism and stresses its ability to advance careers. When party leaders want to rally the people these days, they appeal to patriotism and traditional Chinese values, often based on Confucian principles of civic duty and moral integrity.

“In terms of the evolution of the Chinese Communist Party,” said Stanley Rosen, a professor at USC who studies Chinese political trends, “several things have struck me in recent years. First among them is the attempt to use Confucianism as a partial replacement for Marxism as a guiding ideology for cadres and party members.”

Even leading party theoreticians avoid the Marxist-Maoist cant when they describe the duties of the new Communists.

“People now join the party and become cadres,” Xing Bensi wrote in a recent article, “to make the country rich and powerful, to vitalize the Chinese nation and to promote the people’s material well-being and happiness but certainly not to scale the bureaucratic ladder and line their own pockets.”

No Longer a Vanguard of the Working Class

Along the way, say Chinese and overseas scholars, the party has cut off most of its revolutionary roots. “The party is really a decoration,” said one bitter longtime party member, a university professor from Shenyang in northern China. “It is no longer a revolutionary party, much less the ‘vanguard of the working class.’ It is just a ruling party.”

Richard Baum, a China scholar at UCLA, said: “Today’s Chinese Communist Party is not your father’s Oldsmobile. It is younger, better educated, more urbanized and technocratic. In consequence, formal ideology has lost much of its potency--both within and outside of the party.”

Fittingly, when the party propaganda department this week unveiled its huge tribute to China’s achievements since the last national congress in 1992, most of the displays at the sprawling Beijing Exhibition Center were charts and graphs showing profits, investment schedules and infrastructure projects. Presiding over the unveiling ceremony was Hu Jintao, a Qinghua University honors engineering graduate who, at 54, is the youngest member of the all-powerful, seven-member standing committee of the Communist Party Politburo.

Both by his education and his--by Chinese leadership standards--relatively young age, Hu represents the new generation of Communist Party leadership.

To understand just how much the Chinese Communist Party has changed, it is helpful to go back to 1969.

Changing the Face of Ruling Party

That year, at the height of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, the ninth National Party Congress approved a constitution limiting party membership to “workers, poor peasants or lower-middle peasants.” Party members were assigned five essential chores: study the works of Karl Marx, V. I. Lenin and Mao Tse-tung; serve the collective interests, never work for private gain; strive for a united front; consult the masses; and willingly submit to criticism and self-criticism.

As late as 1985, the Chinese Communist Party was a mostly uneducated organization in which intellectuals were mistrusted and often purged. According to the official party newspaper, the People’s Daily, in March 1985, only 4% of the 42 million party members had any university education; only 14% had attended secondary schools, the equivalent of high school in the United States.

In contrast, at roughly the same time in the Soviet Union--then home to the world’s other great Communist regime--almost 30% of party members had completed university studies, and 43% had full secondary education.

But in the past decade, China’s ruling party has undergone a remarkable transformation. Encouraged by Deng Xiaoping, the late “paramount leader,” to seek members who were “youthful, intellectual and expert,” the party shifted its recruitment targets from peasants to professionals.

The main recruitment grounds for party members have shifted from factories and farms to the universities, successful enterprises and army officer corps. The party has even used the Chinese government’s experimental “village democracy project” as a way of seeking new leadership talent.

Under the democracy project, directed by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, nonparty members compete with Communists for positions on the village committees, the lowest level of government in China. More than 80% of China’s villages now elect their five-member village committees.

Some foreign analysts contend that the democracy project poses a long-term challenge to Communist rule.

The party, meanwhile, has attempted to use the project to spot talent. In cases where local Communist officials are defeated by nonparty members, party recruiters sweep into the village to aggressively enlist the winner. Often, a civil affairs official said, they succeed.

The official cited the case of a provincial woman--not a party member--who became popular with villagers after she chased down a corrupt party official and recovered money he had stolen from the village. As a result, she was elected chairwoman of the village committee. A year later, the party succeeded in recruiting her into the ranks.

Normally, it takes two years for a candidate to be accepted in the party. But, as in the case with the Gansu province candidate, the two-year probation can be waived.

All party members, including the country’s top leadership, are required to attend regular meetings of their cell group, which can range in size from as few as three people to as many as several dozen. Party members also pay dues assessed at the rate of 1% of the first $100 of their base annual salary and 3% of anything earned after that.

But compared with the ideologically charged days of the 1960s and 1970s in China, party duties are relatively light. Some party cells meet only once every six months. On big occasions, such as this week’s national party meeting, cell group members will gather to discuss the political and work reports issued by the congress.

Most meetings, however, feature relatively mundane discussions about membership drives and financing. Rarely do party cell discussions range, as they once did, into competitions of political orthodoxy and correct thinking.

Wide Success in Recruitment Efforts

Despite damage to its image after the 1989 army crackdown in and around Tiananmen Square, the party’s recruitment efforts have been widely successful. In fact, the crackdown that killed hundreds, perhaps thousands, of civilians in the capital may have aided party recruiting. Young Chinese who saw hope for opposition politics and democracy in the 1989 demonstrations were forced to recognize the Communist Party as the only game in town.

“After 1989,” said the young business executive, “people realized that the party was not only still alive, it was not replaceable for at least 20 years.” He joined the party in 1989, shortly after the crackdown.

According to statistics released this year by its organization committee, the party has increased from 48 million members five years ago to more than 58 million today.

Most of these new recruits are from the younger, educated strata of society. The committee said that more than 43% now have secondary education or higher. The party is also much younger than before; almost a quarter of the party membership is younger than 35.

By seeking out the country’s best and brightest, the party has largely reinvented itself as a quicker means to a prosperous, profitable end. “You could probably do it without joining the party,” said the young Beijing furniture magnate, who like other youthful members interviewed requested that his name not be used for this story. “It would just take longer.”

Compared with the revolutionary party that once had the ability to fill Tiananmen Square with enraptured youth, smitten with the cult of Mao, these modern members are a pale lot. Many intercity soccer matches inspire more enthusiasm than party political rallies.

“The current generation in power,” said economist Fan Gang in an interview, “is still attached to ideology. But in five years, the next generation may not be. The new generation has not made the same commitment to ideology.”

In this regard, said Baum, an expert on Chinese politics, the party’s evolution is analogous to the history of religion.

“When a pristine religious sect succeeds in becoming an established denomination,” Baum said, “a routinization of charisma inevitably occurs. Considerations of doctrinal purity, so important in the initial stages of a sectarian movement, diminish in importance, while the strong bonds of solidarity between leader and disciples, generally forged in the crucible of protracted struggle against establishment forces, become attenuated.

“Within one or two generations,” he added, “the successful denomination begins to ‘metamorphize’ into an established church, with formal roles, offices, emoluments and hierarchies replacing the earlier community of true believers. . . . Socioeconomic interests displace millenarian goals, and elite recruitment begins to emphasize technical rather than doctrinal qualities.”

This is not to say that all Chinese Communists are happy about the de-emphasis on ideology in their party. “We are not taught values, things we can believe in,” said the young executive, who said he longs for the day when the moral values of the party will be restored. “Right now, not many people are talking about principles. People are more interested in money and getting ahead. But my hope is that it is a cycle, and in 10 years, they will realize that money is not everything. At that point the values of the party--including public service--could make a comeback.”

Some Chinese political dissidents see both potential benefits and hidden dangers to the party’s transformation from an ideological to a ruling party.

Fang Lizhi, a physicist who fled the country in 1990 after seeking asylum in the U.S. Embassy in Beijing, sees parallels to the archrival Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang, in Taiwan, saying: “Their basic economic policy (half free market, half government control), politics (authoritarianism), diplomacy (half nationalism, half trading), membership composition (party politician, businessman and army man) and their main problem (corruption) are completely the same.”

This gives Fang, who lives in the U.S., some hope for the future. Under the right circumstances, he said, the party could evolve peacefully into a democratic system.

Increasing Elitism May Pose a Threat

But the alternative to Fang’s positive scenario is that the increasing elitism of the party could make things worse. Recent surveys of factory workers--the onetime backbone of the party--show that many feel alienated from the party that once espoused their cause above all others.

“A considerable number of party members,” the leftist magazine Modern Ideological Trends said in a recent article, “in their own hearts do not recognize themselves as party members. They have abandoned the realizing of communism as their highest ideal. This is the attitude of a considerable number of workers, and this attitude is expanding by the day. If this continues, the prospects will be dreadful to contemplate.”

* PARTY CONGRESS BEGINS: The 15th party congress in Beijing will pave the way for a new generation of leaders. A5

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.