Transfusions Help Sickle Cell Children

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Routine blood transfusions for children with sickle cell anemia who are at high risk for stroke can dramatically reduce the chances of a stroke occurring, federal health officials announced Thursday.

“Although this is not a cure, transfusion offers these children the hope of avoiding the devastating consequences of stroke,” said Dr. Claude Lenfant, director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, which released the new findings during a national conference here on sickle cell disease.

The research showed that administering a blood transfusion about once every three or four weeks cut the stroke rate by 90%, results so compelling that scientists ended the trial 16 months early and have begun notifying doctors of their findings.

About 2,500 children in the United States have the disease, and about 10% of them experience strokes, one of the more serious complications of the condition.

Sickle cell anemia is the most common genetic blood disorder in the United States, affecting about 1 in 500 African American newborns and 1 in 1,000 Latino newborns annually. There are about 72,000 people in this country who are afflicted.

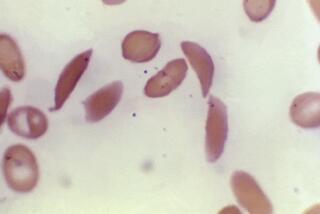

In patients with the disease, abnormal hemoglobin molecules in the red blood cells tend to damage the red cell walls, causing them to stick to blood vessel walls.

This can result in the development of narrowed or blocked blood vessels, depriving the organs and tissues of oxygen-carrying blood.

When this occurs in the brain, a stroke can result. This type of stroke--known as a cerebral infarction--occurs primarily in children.

A special screening tool can identify children at risk, and the results of the study now mean doctors no longer will have to wait until a child has a stroke before beginning treatment.

“We can now intervene before brain damage from stroke takes place, and actually prevent the stroke,” said Dr. Robert Adams, professor of neurology at the Medical College of Georgia and lead investigator on the study.

Children with the disease can be screened to determine whether they are vulnerable to stroke using an ultrasound technique called transcranial doppler, which measures the velocity of blood flow in the brain.

High velocities in one or more major arteries of the brain likely indicate a significant narrowing in key blood vessels that supply the brain, a condition that greatly increases the risk of a stroke.

Once a child with sickle cell anemia experiences a stroke, there is an 80% chance that another stroke will occur. The effects can be extremely damaging, impairing a child’s ability to move, speak and learn, and can in some cases be fatal.

Transfusions keep the abnormal sickle hemoglobin in the blood at less than 30% of the total hemoglobin, lowering the chances of blockage.

In the trial, 130 children age 2 to 16 who have the disease and were found to be at high risk for stroke were recruited from 14 U.S. and Canadian sickle cell centers between February 1995, and October 1996. Sixty-three children received blood transfusions every three to four weeks, while 67 children received standard supportive care for their condition.

After one year, the rate of strokes in the group treated with transfusions was 90% less than that in the standard-care group. Of the 67 children receiving standard care, 10 experienced strokes, compared to one in the transfusion group.

The difference was significant enough to stop the study and give the transfusion treatment to all of the children, researchers said.

The most serious side effect was a buildup of excess iron in the blood of most of the children, which can be toxic in high doses.

The children required chelation therapy, a painful and inconvenient treatment that involves infusions of a drug that removes the iron.