Nobel Winner Reines Dies; He Solved a Physics Puzzle

- Share via

Frederick Reines, a UC Irvine professor whose discovery of one of the smallest particles in the universe set in motion a new course of study and earned him the 1995 Nobel Prize in physics, has died after a long fight against Parkinson’s disease.

Reines was 80. He died late Wednesday at UCI Medical Center in Orange.

“He was a very important man in science,” said UCI physics professor Hank Sobel. “He started a whole new field of physics . . . one of the most exciting fields of physics.”

Martin Perl, who shared the Nobel Prize with Reines for his own work in physics, called his colleague “an energetic man with a fresh view of looking at things.”

“He always had experiments going in different ways from everyone else,” said Perl, a Stanford University physics professor.

Reines’ discovery of what is known as a neutrino has great meaning for science, setting in motion a new way of looking at the universe. But it has little application for daily life.

Reines was born in Paterson, N.J. He received bachelor’s and master’s degrees at Stevens Institute of Technology in New Jersey and a doctorate from New York University.

In a three-page autobiography, Reines said the first time he became interested in science “occurred during a moment of boredom at religious school, when, looking out of the window at twilight through a hand curled to simulate a telescope, I noticed something peculiar about the light; it was the phenomenon of diffraction. That began a fascination with light.”

Though he was more interested in literature and, by his own account, didn’t do well in science at first, he had set his course by the 12th grade. His ambition, he wrote in his senior yearbook, was: “To be a physicist extraordinaire.”

In 1944, before completing his doctoral thesis, he went to work on the Manhattan Project with an elite group of scientists to develop the atomic bomb at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in New Mexico, and stayed for 15 years.

He took a sabbatical in 1951 to think about the subject he would specialize in, and decided to try to find neutrinos. At the time, an Italian physicist had theorized that the subatomic particle existed but no one could prove it. And if, as theorized, it had no mass and no charge, how could you find it?

“It exists but can’t be detected. It seemed an untenable situation,” said UCI physics professor Jonas Schultz.

Reines and a colleague moved their work to a new nuclear reactor on the Savannah River in South Carolina, building an experimental apparatus the size of a small room.

There, in 1956, they were able to prove the neutrino exists. Through the apparatus, he was able to measure the subatomic particle.

“He simply opened this whole new world of neutrino physics,” Perl said.

An Idea, the Hunt, the Discovery

In a 1985 interview with The Times, Reines tried to explain the importance of his discovery.

“I don’t say that the neutrino is going to be a practical thing,” he said. “But it has been a time-honored pattern that science leads, and then technology comes along, and then, put together, these things make an enormous difference in how we live.”

He continued his research on neutrinos, working in a South African gold mine to find the first neutrinos produced in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. In 1988, Reines and his fellow scientists used a detector at the bottom of a salt mine in Ohio to pick up a spurt of neutrinos from an exploding star, strengthening theories about the universe.

“It’s like listening for a gnat’s whisper in a hurricane,” Reines said.

Reines left Los Alamos in 1959 to become head of the physics department at Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland. He moved to UCI in 1966 as the founding dean of the School of Physical Sciences. He went back to teaching and research full time in 1974 and retired in 1988, becoming professor emeritus.

“As a scientist, he was a man of tremendous imagination and vision,” Schultz said. “He always wanted to do experiments to demonstrate the important principles of physics.”

Reines was a big, strong-looking man, a college gymnast who liked to arm wrestle.

“He was always the center of conversations, physics and otherwise,” Perl said. He recalled a time the two were at the Moscow airport and became so engrossed in a conversation about physics that they missed their plane.

While an undergraduate, Reines was interested in singing and drama and took singing lessons from a voice coach at the Metropolitan Opera.

“Between college and graduate school, I even thought briefly about pursuing a professional signing career, but ultimately decided against it,” Reines wrote in his autobiography.

But the Gilbert and Sullivan fan never lost his interest in singing and acting. While teaching at Case, he performed with the chorus of the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra.

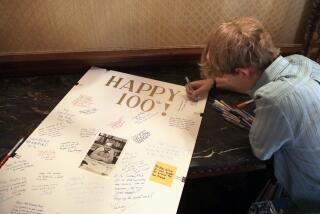

Three years ago, Reines was in the hospital when the Royal Swedish Academy announced that he had received one of the world’s most prestigious prizes. He was still weak when the king of Sweden presented him with the Nobel award at the Stockholm Concert House. In a touching moment, his young granddaughter hugged Reines around the legs as he accepted congratulations.

Besides winning the Nobel, Reines received the National Medal of Science, the Franklin Medal by the Benjamin Franklin Institute Committee on Science and the Arts, the Bruno Rossi Prize and the J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize. He also was named to the National Academy of Sciences.

He is survived by his wife, Sylvia; a son, Robert G. Reines of Ojo Sarco, N.M.; a daughter, Alisa K. Cowden of Trumansburg, N.Y., and six grandchildren. A funeral service will be private, but a campus memorial is being planned.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.