Comfort and Conflict

- Share via

When an independent scientific panel recently reported finding no strong evidence linking silicone breast implants to illness, manufacturers and many plastic surgeons took heart. After all, they have insisted all along that the implants pose no health risks--and that women should have the option to choose them.

Despite the claims of some 400,000 women that their implants made them seriously ill--and 6-year-old federal limits on their use--a determined few have sought out silicone through back channels. The main reason: Silicone gel implants look and feel more natural than the salt-water-filled alternative.

A few women have traveled abroad for breast enlargement in countries where silicone implants are not restricted; others have obtained the implants overseas and found U.S. doctors willing to defy a 1992 moratorium and give them the silicone contours of their dreams.

Dr. C. Lin Puckett, president-elect of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, called the report’s findings “resoundingly reassuring” for prospective patients and implant recipients. Women “are still being bombarded by information from special interest groups who are telling people that they are unsafe and cause diseases.”

Since implants first came on the scene in the 1960s, more than 1 million women have turned to doctors for the breasts their genes didn’t provide. Each year, an estimated 126,000 women undergo cosmetic breast enlargement.

Most new implants are saline. Since 1992, the FDA has limited silicone gel implants to clinical studies of breast reconstruction after mastectomy, correction of deformities or replacement of damaged implants. Doctors are required to file reports with the two remaining U.S. manufacturers, both Santa Barbara-based, which forward the information to regulators.

Silicone critics oppose FDA approval. They cite frequent rupture, silicone leakage and painful hardening of the scar tissue that forms around the implant, as well as severe illnesses that some women blame on synthetic material in their bodies.

To date, no one has proved implants cause disease. But “that’s not the same thing as saying there’s no evidence and it’s not the same thing as saying implants are safe,” warns Diana Zuckerman, an epidemiologist and director of research and policy for the Institute for Women’s Policy Research in Washington.

She says past research looked only for specific diseases, like the tissue-thickening illness called scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis or the immune system disorder lupus, which are “very hard to study unless you have a very large number of women with implants” as subjects. Most studies also followed women for too short a time.

New data is coming, including research results plastic surgeons are reporting to Mentor Corp. and McGhan Medical Corp., and investigations conducted by the FDA and the National Cancer Institute. But FDA approval, based in part on those findings, could be years off.

Unwilling to wait, some healthy women, guided by word-of-mouth referrals, tap a black market that connects them with U.S.-made implants from overseas and U.S. doctors willing to perform the surgery. In some cases, a middleman purchases the implants from suppliers in countries that include Mexico and Brazil and arranges shipment to patients who have paid cash upfront.

*

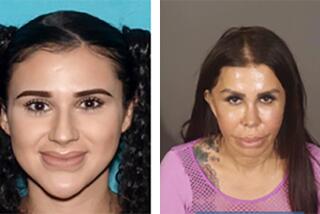

That’s how Lisa Blake, a 33-year-old Los Angeles software executive, got hold of gel implants. She then brought them to a respected, board-certified Los Angeles plastic surgeon who friends said would perform the surgery.

“I had to buy three sets” in case of defects or complications, she recalled. “You get two sets of the size you really want and another size, preferably [smaller]” in case the others are too large.

The surgery didn’t change her personal life or psyche--just the way her clothes fit.

“I don’t think it made me anymore anything--other than larger up top. I’m just more in proportion now.”

Practical at heart, she researched saline and silicone, talked to friends with implants and scanned the Internet, where she read that the percentage of illnesses among women with silicone implants “wasn’t much different from the female population as a whole.”

The Dec. 1 implant report prepared for U.S. District Judge Sam C. Pointer in Alabama, who is overseeing implant litigation, eased some residual worries since her operation.

“I’ve been really watching what’s happening in my body closer--every earache.” The possibility of illness remains “in the back of my mind,” but with the latest report, “it’s further back.”

Should scientists ever establish that implants cause disease, “I’ll take them out,” she says. “I was fully aware that I was making this decision and I was the one that was going to deal with the consequences.”

*

Sally, a 23-year-old television production associate who asked that her full name not be used, was prepared to have the same doctor use silicone to turn her less-than-A-cup breasts into full B cups. She knew “it’s not really legal right now.”

Ultimately, cost pushed her to saline. Next month, she’ll undergo surgery to get saline-enhanced breasts proportionate to her 5-foot-10 athletic frame. She’ll pay about $750 for the saline implants--the silicone versions would have cost her $2,200--and another $4,750 for the surgery.

The report to Judge Pointer left her “a little more reassured and a little more disappointed that I can’t afford” silicone.

Surgeons who will implant silicone for breast enlargement say they’re providing women a choice the government denies and provide full informed consent. The Los Angeles surgeon criticized the FDA for an inconsistent policy that bans silicone gel for some women and permits it for others.

Puckett, head of the plastic surgery program at the University of Missouri in Columbia, is sure other doctors skirt the rules, but “I don’t think it’s widespread among board-certified plastic surgeons. The truth is, the current feeling would be . . . that there’s nothing medically unsafe in doing that, but being that it’s illegal, I certainly couldn’t encourage or condone that.”

*

Dr. Jon Perlman, a Beverly Hills plastic surgeon, said he still finds it “shocking that reputable doctors would risk their license” or malpractice insurance.

The FDA is aware of ban breaking, said Dr. Bruce Burlington, director of the agency’s Center for Devices and Radiological Control. But the agency’s hands are tied: “We do know Congress does not want the FDA regulating the practice of medicine.”

Although doctors with patients in the silicone trials may push the restrictions by including reconstruction for excessively “droopy” breasts, Perlman is among those defending that as a perfectly legitimate application.

Other plastic surgeons are troubled by silicone implants in general.

“I put in hundreds, thousands, most of which I wish I hadn’t done,” said Dr. Edward P. Melmed, a Dallas plastic surgeon who has removed 450 pairs in the last five years. He contends that a small percentage of silicone implant recipients develop a complex of symptoms like the chronic pain syndrome fibromyalgia and what some Gulf War veterans suffer. He suspects some yet-to-be-isolated chemical could be at work.

Ultimately, the FDA will decide whether the science and company data prove the products safe.

Dr. Susan Alpert, director of the office of device evaluation in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, says the implants were on the market before the agency required manufacturers to prove devices safe before sale.

In the early 1990s, the FDA asked manufacturers to submit data to support FDA approval.

“When they believe they’re ready and they submit, we’ll make a final decision,” she said. If the FDA says no, gel implants will be more tightly restricted.

Burlington said Thursday that he had not seen the report to the judge but stressed that the FDA will conduct its own analysis of the science and the company’s patient records.

“The opinion formed by others is not dismissed, but it’s not part of the core of the FDA’s decision,” he said.

*

In the meantime, implant manufacturers contend American women want silicone.

“The FDA has always recognized that silicone gel needed to be available to surgeons and to women, from the beginning of this moratorium. There is significant demand for silicone gel,” said Jeff Barber, a spokesman for Inamed Corp. in Las Vegas, the parent to McGhan Medical Corp. He estimated it could take another three years of study before the company presents the FDA with its data.

Tony Getty, the corporate president for Mentor Corp., says his company hopes to submit an application for broader use of silicone in reconstruction next year but has no near-term plans to apply for cosmetic use.

Although Mentor sees a rich market in silicone, “politically, this is still a hot potato,” Getty says.

He may have put it best when he said: “Even if the FDA came out and said these are as safe as drinking water, the controversy would still rage. I think we’ll be studying these things forever.”