New Maryland Research Lab to Probe Deadliest Organisms

- Share via

WASHINGTON — In the coming months, the National Institutes of Health plans to open a research laboratory that, by its very nature, will ensure its membership in an exclusive club.

The lab will be one of only three sites in the nation--one of only a few in the world--equipped to handle the most lethal organisms known to science.

Like its counterparts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta and the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases in Frederick, Md., the NIH facility in Bethesda, Md., will be a “BL-4” lab--biosafety level 4.

This is the designation for scientific work involving the most danger and requiring the greatest degree of containment and security. The $4.9-million lab will be secured by 24-hour guard and video cameras; the rooms will be equipped with systems and backups that purify the air and water that leave the lab.

The scientists inside will wear cumbersome biohazard “spacesuits,” breathe oxygen through umbilical-like coils tethered to their belts, and leave only after undergoing special decontamination procedures, including a chemical shower.

Lab employees will be required to work with a “buddy” and will not even be allowed to remove their notebooks from the “hot zone”--there will be a fax machine and computer inside the lab.

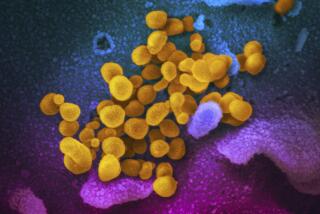

Such precautions are designed to allow researchers to safely study the most dangerous of microbes, those that are highly infectious, incurable, fatal or unknown.

For example, it was the BL-4 lab at the CDC that studied the ebola virus when it was killing scores of people in Africa during its last major outbreak in 1995.

However, unlike the CDC and U.S. Army labs, the NIH lab does not plan to grapple with baffling outbreaks of diseases of unknown origin, at least not just yet.

Rather, its initial work will focus on mutant strains of tuberculosis that have become resistant to available antibiotics and pose an alarming threat around the world--TB infects an estimated 30 million people worldwide annually and kills 3 million, about 2,000 of them in the United States.

The need for increased research in this area has been growing as AIDS--whose sufferers tend to be more susceptible to TB--has spread globally.

The impetus for the new lab came from NIH’s National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the government’s primary research agency on AIDS that increasingly has been turning its attention to tuberculosis.

“These kinds of labs are expensive to run . . . and you have to have a significant enough research effort to justify it,” said Dr. John La Montagne, director of the allergy institute.

Discussing the precautions under which the lab will operate, La Montagne said: “Most of the experiments that have to be done involve animals, and that will generate aerosols [organisms that are airborne]. You simply cannot do that kind of work on an open counter top.”

Unlike Canada and Japan, where plans for similar labs have been stymied by opposition from residents, reaction to the NIH lab among community leaders has been minimal.

Neighborhood groups have clashed with NIH in the past over several contentious issues, including incinerators that dispose of medical waste. But several years ago, the agency initiated a dialogue with community groups to discuss mutual concerns.

NIH officials have stressed that it is unlikely their facility ever will study exotic or unidentified deadly agents, given that the CDC and Army labs already handle that chore. In fact, a special review committee has been set up to approve all research.

Also, the TB organisms that will be under study in the lab “are already everywhere,” said Janyce Hedetniemi, who heads the NIH community liaison office. “It’s not like we’ll be dealing with something that could escape and hurt people. . . . It’s the worker conducting the research who needs to be protected.”

Ginny Miller, who chairs a local citizens group, agreed that residents are comfortable with the prospective facility. “I do think all our questions have been answered,” she said. “And we’re OK with it.”