World History as Shaped by Illness

- Share via

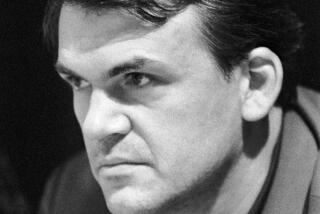

It’s unlikely that you’ll meet a physician like Miroslav Holub the next time you visit your local HMO.

Holub is the kind of polymath Eastern Europe specializes in producing. Born in 1923, he is an immunologist as well as a prominent Czech poet and essayist. He has worked in a psychiatric ward and as an editor, published 16 books of poems, although his work was banned for more than a decade and earned both an MD and a PhD.

But don’t let any of this put you off. In “Shedding Life,” Holub ranges over topics from laboratory pigs to political totalitarianism, from a 17th century bacterial experiment to modern-day slavery, from the death of butterflies to the Czech national character. He is precise, wry, skeptical, humane, witty, sad and optimistic. He is a master at discerning the links between scientific and philosophical truths. He is a cross between Lewis Thomas and Milan Kundera; he is saturated with the particular, peculiar understanding that life is tragic and unbearably precious too.

Both history (especially Czech history) and science have taught Holub to discard Manichaean categories. He rejects the dichotomy between health (which is presumably good) and disease (ostensibly bad). In fact, he writes, both cultural and evolutionary history have been determined by illness as much as by health, and we, as a species, have benefited from each.

He writes: “[T]he basis of the contemporary human being is derived not only from cultural traditions but also from the history of human diseases . . . We can describe human history equally well as a long development or as a long disease.”

Holub is an eloquent defender of the scientific method against attacks from fundamentalists of all kinds: religious, postmodern, New Age, ecological. For Holub, science is a social activity: “Seeing something alone is only for visionaries, fanatics and frauds.” It is liberating, for it “rids us of demons sprouting in the fertile soil of fear of progress, which includes human liberation from natural fate, from oppression, from disease, and from inane minds.”

Science is self-reflective, “anxious because it is in a state of permanent doubt about itself.” It is democratic: “Every totalitarian system, including the one that just ended, is antiscientific.” And it is ethical, for “to think properly is a moral principle” that fosters “ ‘the habit of truth.’ ”

The interrelationship between morality and science is clarified in Holub’s concluding essay, titled simply, “No.” Holub is bored by juvenile, romantic negations--what he terms the “obsessive, neurotic noes.” But he is highly interested in the quiet, specific, disciplined ability of people (and peoples) to say no: no to mothers, fathers, professors, commissars--and no, too, to dogmas, simple certainties and unquestioned traditions: “This is an important aspect of dignity, of sanity and maturity and freedom.”

He then notes that the immune system too is “a device for turning yeses . . . into noes.” Indeed, he continues, evolution itself “is in one basic respect a no to conservation, . . . and it represents the only cosmically successful no to stability.”

For Holub the scientist, our survival as a species depends on the complex interplay between rejection and inclusion; for Holub the poet, our personal affirmations make sense only in the context of “the vital necessity” of noes.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.