Criminal Investigators Find Clues in Surprising Places

- Share via

NEW YORK — The bank robber wore a mask, a parka and blue jeans. The pants told Richard Vorder Bruegge of the FBI everything he needed to know.

Just as a wad of gum spoke to Dr. Dennis Asen. And a piece of weatherstripping helped a prosecutor nail a rapist.

To the untrained eye, none of these items looked unusual. But they revealed enough to play a part in criminal cases that concluded within the last year or so. They show it doesn’t take a dramatic bloody glove or a high-tech DNA analysis to put somebody at a crime scene.

Sometimes it just takes a close look.

Try this: Notice the string of dark and light blotches that runs along the leg seams of well-worn jeans. The pattern looks like a bar code. Vorder Bruegge thinks it’s as distinctive as fingerprints.

The pattern arises from the way jeans are made. When jeans are stitched, the operator pushes fabric through the sewing machine by hand, a bit at a time. The material on the bottom puckers, so when the sewing is done, it ends up in an irregular, undulating pattern of ridges and valleys.

As the jeans wear, the dye fades faster from denim that’s stitched over a ridge than over a valley. The result: light and dark blotches with irregular spacings and widths.

Vorder Bruegge hopes to do mathematical analysis and compare a lot of blue jeans to see if that bar code pattern really is distinctive.

He used his observations last year, testifying in Spokane, Wash., against the robber. The finely detailed 35-mm film of the bank’s camera offered him an eyeful. Beside the bar-code pattern on the outside of the right pants leg, he saw other traits, including an H-shaped wear pattern near the left cuff.

The overall collection of traits matched one of 26 pairs of jeans seized from the homes of several suspects, and none of 34 pairs offered by defense lawyers.

“The bank robber depicted is wearing this pair of pants,” he testified while holding up a pair of Plain Pockets. “I’m 100% certain.”

The suspect was convicted, although the verdict is on appeal. Prosecutor Tom Rice called the blue jeans testimony pivotal.

The cases involving weatherstripping and chewing gum are unusual uses of a standard forensic practice, analyzing bite marks.

Dr. Norman “Skip” Sperber, chief forensic dentist for San Diego and Imperial counties in California, had his doubts about the piece of weatherstripping that an investigator handed him early last year.

A 16-year-old girl had been kidnapped by a man who drove her to a secluded grove in his pickup. While she was outside the truck and bent over near one of the doors, she bit the door’s weatherstripping in hopes of leaving evidence behind.

Eventually, the man was arrested. The truck had been sold, and authorities didn’t find it until three days before the trial. The girl identified it, remembered her bite and pointed out the spot.

By the time Sperber got the yard-long piece of weatherstripping, it had been two years since the girl bit it.

Peering closely, Sperber saw four tiny rectangles, the marks of four lower teeth. One was slightly out of line with the others--a standout trait that makes a forensic dentist smile. Sperber quickly turned to a cast of the girl’s teeth.

“I noticed one of her lower teeth in the model sticking out,” he said. “I saw it was the same tooth. . . . At that point I was really kind of exhilarated.”

Sperber later demonstrated the match to a jury. The man was convicted. The verdict is on appeal, but the bite marks are not at issue.

The weatherstripping “was probably very crucial evidence for the jury,” said prosecutor Kimberly Smith, deputy district attorney for Tulare County in Visalia, Calif.

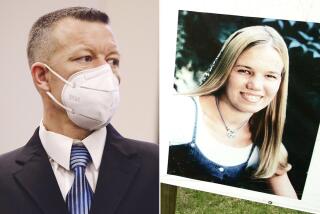

Like Sperber, Asen, the forensic dentist from Allentown, Pa., was skeptical when a cop called last year about a wad of gum. Police had found it near the body of a murdered 13-year-old girl, and soon after arrested a suspect. Could Asen match the gum to the man?

Gum is easily distorted when it’s chewed, handled and spat, making it a lousy bet for bite marks. But Asen found that this wad had definite marks from four upper and four lower teeth. Before long, he was in a prison to make a mold of the suspect’s teeth.

Later, he duplicated the teeth and the piece of gum. Then he put the models together, placing the bogus gum in a spot where one tooth was noticeably out of line.

“It just went boom, right into position,” Asen said. A match.

The suspect pleaded guilty in April, so Asen never had to testify. If he had, his evidence would have run up against a different identification tool: Lab tests of the gum found DNA that didn’t come from the suspect.

Two conflicting messages from one wad of gum. What’s a prosecutor to do?

“It was sort of a double-edged sword,” said John Morganelli, district attorney for Northampton County. “If the case had gone to trial, we decided we were going to give this all to the jury,” he said, “and let them figure it out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.