High Court to Hear Foster-Notes Dispute

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court dealt a setback Monday to independent counsel Kenneth W. Starr by agreeing to hear a lawyer’s challenge to one of Starr’s many subpoenas for private notes.

The court said it will rule early next year on whether a lawyer who consulted with former Clinton aide Vincent Foster just nine days before Foster’s suicide can keep their conversation confidential. James Hamilton, the lawyer, invoked the traditional attorney-client privilege when he refused to give Starr his three pages of notes.

But last year, the U.S. court of appeals here, in a ruling that surprised many legal observers, declared that the attorney-client privilege died with the client. Because Foster is dead, he no longer needs to fear prosecution, the appeals court ruled. Therefore, the attorney has no reason to shield the notes from the prosecutor.

Hamilton appealed to the Supreme Court and was joined by the American Bar Assn. and the National Assn. of Criminal Defense Lawyers. They argued that millions of Americans consult a lawyer in the final years of their lives. The lawyers said they have an obligation to keep their client’s confidences, even after death.

Starr urged the justices to reject the appeal on grounds that it “would delay an important grand jury investigation.”

Monday’s announcement granting a full review is good news for the White House, even though the case involves only a minor aspect of Starr’s far-flung inquiry, which began as an investigation of a failed Ozarks real estate deal called Whitewater and has ranged into whether President Clinton had sex with a former intern and then urged her and others to lie about it. Starr is seeking Hamilton’s notes as part of his inquiry into the sudden firing of seven White House travel office workers in May 1993.

The case (Swidler & Berlin vs. United State, 97-1192) will be heard in the fall. It promises to reopen one of the saddest stories of the Clinton years in Washington.

A boyhood friend of Clinton and a Little Rock law partner of First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, Foster came to Washington in 1993 to join the new administration. He was named a deputy White House counsel.

But like so many of Clinton’s Arkansas friends, he was soon ensnared in some of the controversies that have dogged the administration. One concerned the travel office firings.

Republican critics said the first lady was secretly behind the firings and then lied about her role in it. Foster, apparently fearing that he would be called to testify before Congress about the matter, hired Hamilton as his private lawyer.

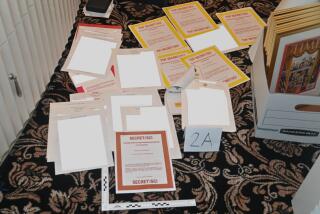

They spoke for two hours on July 13, 1993. Hamilton took notes and wrote the word “Privileged” at the top.

At midday on July 20, Foster left the White House, drove to a Virginia park overlooking the Potomac River and shot himself.

Starr subpoenaed Hamilton’s notes in 1995. A federal judge here blocked the subpoena, but the U.S. court of appeals, on a 2-1 vote, upheld it last year. Usually, a claim of confidentiality between a lawyer and a client is honored, the court said, but the balance changes when the client dies.

There is no “concern for criminal liability after death,” wrote Judge Stephan Williams, and many “view history’s claims to truth as more deserving” than preserving confidentiality. But Hamilton argued that the client’s concern for his reputation extends beyond the grave, and that a lawyer should honor his confidences.

*

Twice last year, the high court rebuffed Clinton when he sought legal protection.

In a 9-0 ruling in May, the justices said a president is not immune from answering a civil suit over his private behavior. That ruling cleared the way for depositions and a trial in the Paula Corbin Jones sexual harassment case.

In June, the court rejected the Clintons’ bid to shield notes taken by two White House lawyers who spoke to the first lady after she appeared before the grand jury. A lower court said the White House lawyers are federal officers first, with a duty to assist a federal prosecutor such as Starr.

Those two decisions suggested that the court would not protect the Clintons when they claimed various legal privileges.

Also on Monday, the court said it would review the constitutionality of the federal law that makes carjacking a crime.

Though the high court is usually seen as tough on crime, the justices have been concerned about the overlap between federal and state crime laws. For instance, three years ago, the justices struck down a federal law that made it a crime to have a gun near a school.

In the fall, the justices will review the case of Nathaniel Jones, who was convicted of a violent carjacking near Bakersfield. The arguments will not concern whether Jones was properly convicted but whether Congress had the power to make this a federal crime (Jones vs. United States, 97-6203).

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.