Studio Tour

- Share via

SINGAPORE — This island city-state is an artist’s mecca, the new Paris of Asia, home to some of the best contemporary artists practicing along that multicultural wheel, the Pacific Rim. You see their works displayed everywhere in Singapore--on the streets, in hotel lobbies, along the riverfront, lining the concourses of Changi Airport.

Sculpture, painting, ceramic and graphic arts are flourishing here as never before. With reference points drawn from China and India, from multifaceted Malay cultures to modern and contemporary Western art, Singapore artists make up an eclectic blend of the traditional and the new. In Hollywood, every waiter may have a script he’s working on in his home computer, but in Singapore everyone seems to have a half-finished canvas tucked away in a corner.

But in order to check out the art scene in Singapore, you don’t head for the nearest gallery, as in most Western cities. Here, “Meet the Artist” is the name of the game.

One of the most attractive things about Singapore artworks is modest pricing. This means that most artists sell from their homes or studios directly to the public, bypassing the bite of gallery percentages.

On two visits to Singapore, one in 1994 and the most recent last February with my mother and father (who in the 1980s worked in Asia and remembered Singapore as a haven of civilized calm amid the often chaotic world of Asian business), I made arrangements to visit a group of artists whose work I became interested in after researching an article on contemporary Asian art.

The Singapore phone book is useless for contacting artists: too many identical names. So I turned for help to the remarkably well-organized Singapore Tourism Board (see Guidebook). Over the phone, I gave the names of eight artists whose work particularly interested me to a highly efficient young lady named Tania who spoke perfect English. She got back to me at my hotel the next day with telephone numbers. That was the easy part.

It was often a real challenge to find the artists. In this consciously cosmopolitan city, there is no specific artists’ quarter. They live in apartments, converted shop houses and aged dwellings in far-flung corners of the island. But none of them was more than a 20-minute taxi ride (about $10) from my hotel, the Pan Pacific on Raffles Boulevard.

The artists I visited are among Singapore’s most recognized. Their pieces can be costly (topping out at about $35,000 for an important piece by Goh Beng Kwan), but even casual collectors can find things (a small piece by Iskandar Jalil, for example, can be as little as $10). You don’t have to buy anything. High pressure sales are considered bad manners here.

I finally located artist Tan Swie Hian, the only artist in Singapore to have his own private museum, in his studio, one of the old buildings of the La Salle College of Arts in the Malay quarter of Geyland Sunrong. Clad in shorts, T-shirt and rubber thongs, Tan had just finished setting up a new stereo system and was particularly proud of its acoustics. His studio, even with the windows open and ceiling fan racing, was boiling hot. Sitting on the equator, even in February, Singapore’s temperature resonates with heat and humidity and never lets you forget you’re in the tropics.

*

“Come have lunch,” he invited me impulsively, and off we went to a small neighborhood restaurant where Chinese families sit at Sunday luncheon around linen-covered tables. Dining with an artist was a rare and unusual treat; over steamed fish, spring onions and rice, Tan told me of the difficulties of producing innovative art in Singapore. As in many societies dependent on bureaucracy, the Singapore Arts Council is lethargic at best in their encouragement of local artists. But despite this, Tan, who paints in oils, acrylics and ink, and sculpts in clay and stone, has managed to make his mark on the international art world.

In 1994, he was invited to create a work of engraved calligraphy on a group of huge boulders located at the controversial Three Gorges hydroelectric dam project on the Yangtze River in China. The ambitious son of a fisherman, Tan has used Buddhism as the lodestone of his art. Buddhist metaphors pop up in his painting and insinuate themselves in his sculpture. “When you are in this state of mind,” he says, “you become the grass. You are a butterfly. You are a mountain. You are everything.”

*

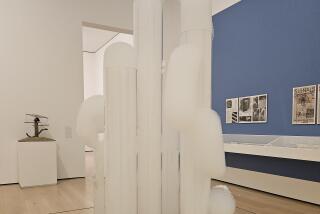

Unlike the contained explosion of Tan Swie Hian’s art, the sculpture of Ng Eng Teng has a reserved, meditative quality. Visible in several public installations around the city, Ng’s style is immediately recognizable in its curved lines that spiral inward in ever-tightening circles until it reaches a core of truth.

Although he sometimes works in clay, his principal medium is ciment-fondu, an industrial cement to which different aggregates can be added to achieve an array of textures. He learned the technique from British sculptor Jean Bullock, who lived in Singapore in the late 1950s. Ng went on to study art in Britain and then returned to Singapore, where he set up his first kiln with his father’s help. Today, Ng’s studio is the breezeway, garden compound and basement of his mother’s Joo Chiat district house.

He uses his pieces to involve children. “I began a series of ciment-fondu balls,” he told me, “about 2 feet in diameter, oxidized to look like bronze and hollowed to allow bells and rattles to be inserted inside them. I wanted to bring sculpture down to the ground, to interact with it, to be playful. Children love to play with the pieces.”

Fellow ceramist Iskandar Jalil is considered one of the founding fathers of Singapore ceramic art. Sitting in the quiet courtyard of his home studio in Jalan Kembangan district, with small samples of his students’ art all around him (he teaches at Temasek Polytechnic School of Design and is a fellow at the Centre for the Arts at National University of Singapore), Jalil explained to me that it is important to him “to work with the local clays of my own country, with the earth that is special to me.”

*

Trained in India and Japan as well as Singapore, Jalil brings an intuitive understanding of these three very different aesthetics to his work. “Nippon and Hindustan [Japan and India] are both so Asian, and yet poles apart in everything,” he said. A retiring, unassuming man, Jalil has had his work presented as gifts by the Singapore government on state occasions. But despite this, he said simply, “I am a teacher. It’s what defines me.”

Pick a medium, any medium, and Singapore has something to offer. For traditional watercolor and Chinese ink brush painting, there is Tan Kian Por. “The art world in Singapore is becoming very commercialized these days,” he complained. “On the other hand the idea of making a living as an artist encourages young people to go into art full time who might not otherwise be willing to take the risk. That much is good.”

In his studio, surrounded by the orchids and tropical fish that he raises, Tan has hung on the wall a scroll of a calligraphy that reads: “Be innovative, carve out a new way and open up new horizons in painting.” It seemed a strange motto for a man so committed to the traditional.

But new horizons are definitely the credo of the hottest--and highest priced--collage artist in town, Goh Beng Kwan. Goh’s style is to incorporate stray bits of paper and objects found in the street into his work. We met in the small cubicle of his framing shop, a business which supplements his income.

Despite the fact that he trained five years in New York, Goh is in love with Asia. “The greatest gift I could wish for a fellow artist,” he said, “would be to see Bali as I saw it for the first time [as a young man]. It was the colors mostly.” He said it made him feel immensely creative.

Goh uses glue and varnish like watercolor to create thin transparencies of shading over paper that he often dyes to a spectrum of tones. Singapore art critic Constance Sheares, in her introduction to a catalog of Goh’s work, compares it to work of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

For batik (a medium of wax and dyes used on fabric) as fine art, Sujak Rahman’s most recent work incorporates a fine mesh overlay of figures in acrylic paint, creating a three-dimensional quality on canvas. Rahman uses watercolors, oils, pastels and acrylics but is known primarily for his abstract paintings, where batik fabric is used as a base to build on. Some of Sujak’s subjects, such as puppets and puppeteers, show an Indonesian influence, but he is also fascinated by the symbolic relationship of mother and child.

*

A new kid on the block--and one of a growing number of women artists--is Tan Chin Chin, who works in mixed media on paper and canvas with a palette of colors drawn from traditional Chinese sources. She is one of the few Singapore artists represented by a gallery.

Having studied in London and now temporarily studying in New York, Tan nevertheless focuses on the mixed cultures of her own hometown in her art. “I like Oriental expressions,” she explained, “and the simplicity and originality of the past.”

The world which Amy Tan (no relation) investigated in “The Joy Luck Club” is the world that Tan Chin Chin explores in her art: the convoluted and often contradictory world of a Chinese childhood outside China. Then she throws in a soupcon of Malay, Indian and Muslim cultural textures for good measure.

If Tan is just gaining stature in the flourishing realm of Singapore art, Thomas Yeo is that realm’s grand old man. His sensuous oils and acrylics, with their striking palette of contrasting colors, hang in museums and collections all over the world. He is also the driving force behind three huge books on the contemporary Singapore art scene.

Yeo has a childlike enthusiasm for the world around him, but also an artistic insight into the psychological effect of that world on his fellow human beings. He describes his abstract landscapes as metaphors for more interior ones. “For me,” he confided, “landscape is an icon, a symbol with more than one interpretation.” As I studied the violent red gashes of color left by his flying palette knife, I could only wonder what traumatic interior landscape he was exploring.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

GUIDEBOOK

Singapore Swings

Getting there: Singapore and United airlines offer direct flights (one stop, no change of planes) to Singapore from LAX. JAL and Northwest have connecting service. Lowest restricted, round-trip fare (on United) is $851.40, including taxes.

Visiting artist studios: Most Singapore artists speak English (Tan Kian Por is an exception, speaking only Chinese). If any difficulties arise contacting an artist, help is available from the Singapore Tourism Board (see address below), or the Singapore National Arts Council, telephone 011-65-270-0722.

Tan Swie Hian, 91 Lorong J Telok Kurau Road; local tel. 744-3987. Paintings sell for up to $15,300.

Ng Eng Teng, 106 Joo Chiat Place; tel. 344-6883. Prices average about $1,500.

Iskandar Jalil, 44 Jalan Kembangan; tel. 780-5729, fax 241-4311. Prices run from $2 to about $600.

Sujak Rahman, No. 1 Jalan Kelabu ASAP; tel. 473-9725. Prices about $1,200 to $17,700.

Tan Kian Por, Block 249 Hougang Ave. 3, No. 02-408; tel./fax 286-7379. Prices from about $170 to $12,100.

Thomas Yeo, the Beaumont, 147 Devonshire Road, No. 02-03; tel. 737-0835, fax 732-9369. Prices from about $2,100 TO $14,700.

Goh Beng Kwan, Block 24, Unit 01, 333 Outram Park; tel. 220-5576. Prices from about $900 to $24,240.

Tan Chin Chin, Blk 114, Potong Pasir Avenue 1, No. 12-866; tel. 282-7537. Prices $1,500 to $13,529. Also sells through Art Focus Gallery in the Centrepoint Mall, 176 Orchard Road; tel. 733-8337, fax 732-04486.

For more information: Singapore Tourism Board, 8484 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 510, Beverly Hills, CA 90211; tel. (213) 852-1901, fax (213) 852-0129.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.