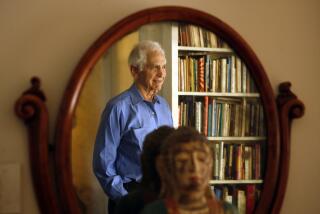

Clark Clifford, Advisor to Four Presidents, Dies at 91

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Former Secretary of Defense Clark M. Clifford, a consummate Washington patrician whose influence helped shape American politics for a half-century, died early Saturday at his home in Washington. He was 91.

Clifford, a key figure in initiating the traumatic and tortuous process of extricating the United States from the Vietnam War, had worked for or counseled almost every Democratic president since Harry S. Truman.

A man of exceptional influence and extraordinary insight into government, Clifford was long regarded as the epitome of the Washington super-lawyer. He was offered a seat on the Supreme Court by Truman and jobs as U.N. ambassador, CIA director, national security advisor and undersecretary of State by Lyndon B. Johnson, but he turned them all down. He preferred to advise.

At key points, Clifford’s influence was pivotal. His ideas contributed to the reorganization and reinvigoration of the Democratic Party, paving the way for Truman’s upset victory. He helped President Kennedy introduce oversight of the intelligence community after the Bay of Pigs debacle and assisted Jimmy Carter in winning ratification of the Panama Canal treaties.

He played major roles in 11 presidential campaigns. He even redesigned the presidential seal.

Clifford, whose Washington career began in 1945 as a naval aide to Truman, was finally tempted by Johnson’s offer to become secretary of Defense because he had drafted the legislation that created the Pentagon. He took his seat on the Cabinet in 1968, the final year of Johnson’s presidency.

Banking Scandal Led to Indictment

But Clifford’s long record of accomplishment was tarnished at the end by his involvement in an international banking scandal.

In 1992, he and a former law partner, Robert A. Altman, were indicted on charges of engaging in fraud and accepting $40 million in bribes. The charges were based on allegations that Cifford and Altman concealed from federal regulators the fact that the foreign-owned Bank of Credit & Commerce International secretly owned First American Bankshares Inc., a major bank holding company the two men had headed since 1982.

Clifford resigned from First American a month after BCCI, and the Pakistani executives who ran it, were accused by the federal government of supporting terrorists, laundering drug money and engaging in massive fraud.

Because of Clifford’s poor health, the charges against him were dropped in 1993. A civil lawsuit arising from the BCCI investigation was settled just last month.

In an interview with The Times, Clifford saw his place in history primarily through the prism of his brief Pentagon job, which he accepted convinced, as was Johnson, that U.S. involvement in Vietnam was a necessary and noble endeavor. But he soon became disillusioned and concluded that the war could not be won without a far greater investment in lives and money than the nation was willing to pay.

His metamorphosis from hawk to dove cost him his close friendship with Johnson, who began large-scale U.S. involvement in the war in 1965. “He was terribly put out with me, and our relationship was never the same again,” Clifford said of Johnson during a lengthy interview with The Times in June 1982.

Nevertheless, Clifford was widely credited with being the person most responsible for persuading Johnson in March 1968 to begin de-escalating the war--a move that led to the convening of peace talks in Paris with North Vietnam.

One Pentagon insider, a dove, said, “Clifford played a preeminent, and I believe the decisive, role” in causing Johnson to reverse his Vietnam policy.

Clifford’s entry into the Johnson Cabinet marked his first return to the federal payroll since he left the White House in 1950 after serving four years as Truman’s special counsel--a job that entailed working as a speech writer and serving as political and legislative advisor. After leaving the White House, Clifford set up his own law firm and soon had such clients as Radio Corp. of America, Phillips Petroleum Co., Standard Oil Co., the Pennsylvania Railroad and the republic of Indonesia. Kennedy, who tapped Clifford in 1960 to help organize his administration, once joked that where others wanted a reward, “you don’t hear Clark clamoring; all he asks in return is that we advertise his law firm on the backs of $1 bills.”

A Man Who Exuded Elegance and Style

Clifford was one of the most elegant figures in Washington. He was noted for his immaculate grooming and wore double-breasted suits when they were long out of style.

As a lawyer, he worked behind a massive desk in a penthouse suite overlooking the White House in what was less an office than a large drawing room with dark paneling, period furniture and Oriental rugs.

“Going to see Clifford was like appearing before a Supreme Court of one,” an acquaintance once said. “He gives you that beautiful smile, and you know he understands your problem and he’ll solve it for you.”

Clark McAdams Clifford was born in a well-to-do family on Christmas Day 1906, in Fort Scott, Kan., but grew up in St. Louis. His father was an official of the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and his mother’s brother, Clark McAdams, for whom he was named, had been an editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

After graduating from Washington University law school in St. Louis in 1928, Clifford joined a St. Louis law firm that specialized in corporate law.

One of Clifford’s clients was James K. “Jake” Vardaman, a businessman and friend of then-Sen. Truman. When Truman became president in 1945, he made Vardaman his naval aide. Vardaman summoned Clifford, who had been commissioned the year before as a Navy lieutenant junior grade, to be his assistant.

Clifford began helping out with speech writing and legal matters, and Truman took a liking to him. When Vardaman was named to the Federal Reserve Board early in 1946, Clifford succeeded him as naval aide. He won Truman’s esteem by writing a tough speech in which the president threatened to draft striking railroad workers into the Army. A few weeks later, Clifford was named special counsel to the president.

Clifford Helped Create Department of Defense

Clifford became the principal architect of legislation that unified the military services and created the Department of Defense.

He was called back into political service by Kennedy in 1960 to prepare a blueprint for the transition from the outgoing administration to the new one. He didn’t officially join the new administration, but Kennedy made him a member and subsequently chairman of his Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board and sought his counsel about reorganizing the Central Intelligence Agency after the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Clifford had never been particularly close to Johnson, but within a week after Kennedy’s assassination, Johnson summoned Clifford to the White House for what became a five-hour discussion. A close, warm relationship soon developed, and before long Clifford was spending more than half his time on presidential assignments, including several fact-finding trips to Vietnam.

Then came the nomination to succeed Robert S. McNamara, who had resigned after seven years as secretary of Defense to become president of the World Bank.

“After I had been in the Pentagon for just a few weeks, my thinking underwent a very serious transformation,” Clifford said in 1982. Following the Communist Tet offensive in January 1968, Johnson named Clifford chairman of a special high-level committee to look into all aspects of U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

From this, Clifford emerged with an added dimension to his post-World War II belief that “Communism was like a cancer and that you had to move promptly and exorcise the cancer before the metastatic process began.” Looking back, Clifford said in his Times interview, “I am absolutely convinced now that the theory was correct, but it should never have been applied to South Vietnam. I think we were wrong to go there in the first place.”

Behind Clifford’s change of mind was the abandonment of an earlier conviction, one held by most top officials in the Johnson administration, that the Vietnam War was a “combined decision on the part of the Soviet Union and Red China” to take over Southeast Asia.

“I am absolutely sure in my own mind that that analysis was incorrect,” Clifford said.

Although the war continued until 1975, Clifford said he regarded his success in helping persuade Johnson to de-escalate the conflict in 1968 as the crowning achievement of his career. An account of the role Clifford played is contained in the book “The Limits of Intervention” by former Air Force Undersecretary Townsend Hoopes.

“He was the single most powerful and effective catalyst of change,” Hoopes wrote of Clifford. “He rallied and gave authoritative voice to the informed and restless opposition within the government, pressing the case for change with intellectual daring, high moral courage, inspired ingenuity and sheer persistence. It was one of the great individual performances in recent American history.”

Clifford is survived by his wife, the former Margery Pepperell Kimball of Boston, whom he met while traveling in Europe in 1929. They were married in 1931 and had three daughters. He also leaves 12 grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.