The Day the Eagle Landed and the Earth Stood Still

- Share via

“Houston . . . the Eagle has landed.”

Those words came at 1:17 p.m., July 20, 1969.

It had been eight years since President John F. Kennedy, locked in a space race and Cold War with the Soviets, asked his closest advisors what space-related achievement America could attain first. They told him: Send a man to the moon.

We can only imagine the pride and anticipation Kennedy would have felt that summer day when astronaut Neil Armstrong’s famous transmission crackled into Mission Control in Houston, announcing the touchdown of the Eagle lunar lander.

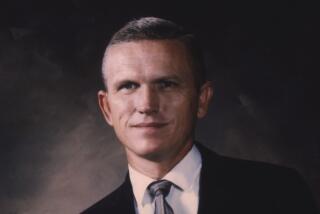

Four days earlier, Apollo 11 commander Armstrong, a stoic Eagle Scout, and his crew, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins, had made their way to the towering Saturn V rocket as it delicately teetered on Pad 39-A of Florida’s Kennedy Space Center.

As they completed a launch checklist 417 items long, Collins thought: “Here I am . . . resident of a Texas suburb . . . about to be shot off to the moon. Yes, to the moon.”

In the moments before liftoff, Collins noticed that Armstrong’s baggy pants pocket looked close enough to snag the abort handle. For an amusing if anxious moment, he imagined the worst: A headline reading, “MOON SHOT FALLS INTO OCEAN . . . Last transmission from Armstrong prior to leaving pad reportedly was ‘OOPS.’ ”

Eleven minutes later, they were in orbit.

As Armstrong and Aldrin readied the lunar module, Collins bade them adieu from the command module: “You cats take it easy on the lunar surface,” he told them.

Several program alarms sounded as the Eagle descended. But ground controllers knew the computer was just being asked to do too much and would postpone noncritical tasks.

Ever so slowly, with lunar dust kicking up, Armstrong and Aldrin guided the Eagle in on the moon’s Sea of Tranquillity.

Not much was made of it at the time, but the two astronauts had only about 15 seconds of fuel left after being forced to maneuver around some surface boulders.

*

Back on Earth, the world stood still in awe. Traffic in Southern California and elsewhere ground to a whispering halt. At Anaheim Stadium, a game between the Angels and the Oakland Athletics was interrupted during the second inning when, at the precise time of the landing, a message appeared on the scoreboard: “We have landed on the moon.” The crowd of 18,000 took to its feet, cheering.

It would be several hours later, at 7:56 p.m., before Armstrong and Aldrin descended the Eagle’s gangway. They struggled to steady the flagpole in the hard lunar soil and Aldrin “dreaded the possibility of the American flag collapsing into the lunar dust in front of the television camera” and 528 million viewers back on Earth.

But the famous flag-planting ceremony went off successfully--as did a phone call to the astronauts from President Richard Nixon, who quipped that it had to be the most historic call ever.

When they returned to Earth, Collins made a point of thanking the thousands whose “blood, sweat and tears” contributed. He was right; about 400,000 American workers from 20,000 companies had worked directly on the Apollo program, many in Southern California.

At Rocketdyne’s laboratory near Chatsworth, where engines for the Apollo missions were built, 6,000 workers had toiled for nearly a decade.

Many other numbers went into the making of a moon mission:

The cost in human lives of America’s quest to land on the moon: three, when astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee died in a fire that erupted during tests of Apollo 1, the first of 10 missions leading up to Apollo 11.

The cost in dollars of the Apollo program: $25 billion.

The weight of the Saturn V rocket that carried Armstrong and company into space: 6 million pounds, the heaviest object that ever flew. The amount of wiring in the Columbia command module: 15 miles.

The number of astronauts who would walk on the moon between 1969 and 1972: 12. The number of American flags planted on moon: six. The other objects left behind on moon: two golf balls hit by astronaut Alan B. Shephard Jr. and a piece of the Wright brothers’ biplane.

The proportion of America’s 270 million residents too young to remember Apollo 11: about half.

Some believe the greatest legacy of the Apollo program is that it opened the door for today’s now-routine commercial space ventures. Others to this day criticize the program as nothing more than a game of one-upmanship with the Soviet Union. Still, no one denies that the plaque the Apollo 11 crew left behind stands as a celestial symbol of the potency of human endeavor. It reads: “Here Men From Planet Earth First Set Foot Upon the Moon. July 1969 AD. We Came in Peace for All Mankind.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.