Some Stars Emit Destructive Flares

- Share via

Providing one more unlikely thing to worry about in the new millennium, Yale astronomers said Wednesday that some stars disturbingly like the sun emit highly destructive, supermassive solar flares, 100 to 10 million times larger than any flare observed on our sun.

In the improbable event that our sun produced the largest of such flares, “it would destroy the Earth’s ozone layer, allowing harmful ultraviolet radiation to flood the Earth and destroy the food chain from the bottom up,” said Yale astronomer Bradley Schaefer.

Such a flare would also produce a variety of less catastrophic consequences, such as disrupting radio communications, frying all orbiting satellites and blacking out power grids worldwide, Schaefer told a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas.

It would also create spectacular auroras visible from the poles to the equator, so we would have something pleasant to look at while we starved, he added.

Fortunately, there is no evidence that the sun has ever emitted such a flare, and astronomers believe it is highly unlikely that it will any time soon.

“We can’t rule out the possibility that [our sun] can make a flare 100 times larger than the most severe previously observed,” said astronomer Lynn Cominsky of Sonoma State University. A flare of that magnitude “would have some effect on the upper atmosphere, but it wouldn’t devastate life on Earth.”

Solar flares are common occurrences that seem to correlate with the 11-year sunspot cycle. They emit clouds of X-rays and charged particles that can be fatal to humans in space and that interfere with radio communications on Earth. They also produce heightened auroras.

Auroras associated with the next round of flares, expected in 2001, might be seen as far south as Northern California.

But the superflares that Schaefer is talking about would dwarf normal solar flares the way a searchlight overpowers a firefly.

Schaefer said he and his colleagues have found evidence of nine such superflares in the universe. The oldest was seen in 1899 by astronomers in Austria, Germany and Italy, who observed it independently and simultaneously while peering through their telescopes.

The most recent two were found by an orbiting X-ray satellite, which observed powerful hourlong blasts of X-irradiation close to the stars it was focusing on.

Schaefer’s team studied each of the stars that produced the superflares and found that they were unexpectedly normal: not rotating fast, not members of a binary (two-star) system and not very young.

2 “They are just normal, everyday, garden variety stars--just like our own sun,” he said.

But he concedes that it is unlikely that our sun has ever emitted one of the larger superflares.

First, there is no evidence of such a flare ever being observed.

Second, had such a superflare happened, it would have produced mass extinction. This type of flare would emit a lot of X-rays, gamma rays and protons that would combine with nitrogen and oxygen in the Earth’s atmosphere to produce nitrous oxide, which would destroy the ozone layer.

“The Earth would be laid bare to solar ultraviolet light, which is a very good killer,” Schaefer said.

In the year or two before the ozone layer could have reconstituted itself, there would have been a mass extinction of many species. But all the known extinction events on Earth have been linked to other causes, he said.

Finally, such a superflare would have left evidence of its passage on other planets. It would have, for example, melted the ice on Saturn’s moons, allowing the water to flow into low areas before it could refreeze. There would thus be relatively smooth sheets of ice rather than the rough, fractured patterns observed by planetary probes.

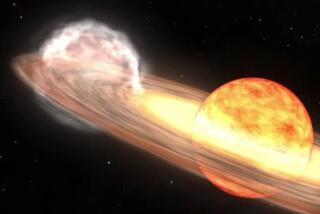

Perhaps even more conclusive is the proposed mechanism for the superflares. Astronomers have previously observed similar flares from stars in binary systems. They believe that the flares are caused by the interaction of the two stars’ magnetic fields, which commingle and trigger an outburst of radiation.

Schaefer speculates that a similar effect could occur if a star was closely circled by a large planet, such as Jupiter, with a strong magnetic field. But the planet would have to be in an orbit as close as Mercury’s, and Mercury has only a weak magnetic field.

“So if this model is correct, then our sun is not going to have [a superflare],” Schaefer said. “This is not something we need to rush to Congress to get money to study. . . . But it might make a good movie.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Sending Out a Flare

No one is sure precisely what causes destructive superflares, but some scientists suggest that they are produced by the interaction of a star’s magnetic field with a large nearby planet’s strong magnetic field. Scientists say it is unlikely that the sun will ever produce a burst of energy of this magnitude.

A: Magnetic field

B: As magnetic fields commingle, they may periodically trigger bursts of energy, called superflares.

C: Nerby planet with a strong magnetic field.