The Oracle of Basel

- Share via

Exhuming the unpublished lectures of great classical scholars, especially from the 19th century, can be a risky business. There may be very good reasons why they never saw the light of day in print. When Nietzsche created his Ubermensch or superman, he had plenty of academic models to inspire him in the Germany of the time, from Johann Gustav Droysen to Theodor Mommsen.

Most of these were natural authoritarians by temperament, heavily involved in the reunification of Germany under Prussian leadership: Their vision of the ancient world took its color, consciously or not, from their political activities. Droysen saw Philip of Macedon (and a fortiori his son Alexander) as a heaven-sent fuhrer destined to knock sense and obedience into the endlessly squabbling Greek states.

Mommsen’s hero was Julius Caesar, who in his view--a highly popular one until Sir Ronald Syme and World War II demolished it--performed a similar rescue mission for the Roman Republic amid the convulsions of civil war. One way and another, imperialism was the leitmotif of German classical scholarship for a very long time.

Mommsen’s impassioned history of the Roman Republic won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1902, but he made continual excuses for not publishing his version of the Augustan age and the Empire: He was too busy with other projects; he lacked the adventurous spirit he once had; he felt the Empire was a bleak period of stagnation and decadence; the hard evidence supplied by inscriptions was inadequate (this, from the master of Roman epigraphy!).

But such concerns did not stop him from lecturing on the topic in the 1880s. Devoted students took copious notes, faithfully transcribing all of Mommsen’s obsessional eccentricities. The notes surfaced in a Nuremberg bookshop in 1980; they were edited and published in 1992, an English translation appearing in 1996. It was at once apparent that Mommsen’s reticence had been more than justified. As that excellent Roman historian G.W. Bowersock wrote:

“The Mommsenian history that has been given to the world is unbelievably bad. It is of no use whatever for comprehending the Roman Empire. It is even more opinionated than the history that had made the young historian’s reputation, but it lacks any kind of insight or depth. Its interest lies principally in exposing the weak flank of a great man.”

Now we are confronted with a similar scenario involving Mommsen’s contemporary, Jacob Burckhardt, author of such classics as “The Age of Constantine” (1852) and “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy” (1860), the latter earning Lord Acton’s accolade as “the most penetrating and subtle treatise on the history of civilization that exists in literature.” Between 1872 and 1885 Burckhardt delivered a series of lectures on Griechische Kulturgeschichte (Greek cultural history). Like Mommsen, he refused to consider his lectures for publication but on different grounds: He anticipated rightly an ultra-hostile reception for the unromantic views he held and the innovative methods he employed on the part of the classical establishment. The art historian in him took a wider view than that adopted by the philologists and narrowly political historians, such as Leopold von Ranke, whose aim was to recapture the past “as it really happened” by a painstaking accumulation of facts.

“In my old age I need peace,” Burckhardt told a friend. But immediately after his death in 1897 the lectures were--against his express wishes--reconstructed by his nephew Jacob Oeri and published in four volumes. The reaction was exactly as he had foreseen. “These Greeks never existed,” sniffed Mommsen. His son-in-law, Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorf, great scholar and blue-blooded Prussian Junker, went further: Burckhardt’s “Griechische Kulturgeschichte,” he proclaimed, “ignores what the scholarship of the last 50 years has achieved in relation to sources, facts, methods and approaches.” The distinguished historian Julius Beloch joined in this chorus of condemnation, dismissing the published text as “a book by a clever dilettante for dilettantes.”

Were they right? On their own terms, yes. Burckhardt had indeed ignored their findings, methods and principles. Yet today he is regarded as the pioneering genius of cultural historiography. The irony of this would not have been lost on him. “History,” he once observed, “is the record of what one age finds worthy of note in another.” One generation’s fashion is another’s inner truth.

Unlike Mommsen’s lectures on the Empire, Burckhardt’s Griechische Kulturgeschichte has always been available to the few scholars determined to run it down. Those four red volumes, printed in old-fashioned Gothic black-letter type, can be found gathering dust on the shelves of most major university libraries. Oeri’s text was re-edited in 1930 and reprinted in 1956. However, American readers without facility in German have had little exposure to this remarkable work, and that little has depended, to a striking degree, on editorial preference. In 1963, there appeared a selection made from an abbreviated text, concentrating on poetry, philosophy, oratory, the historians and the arts (Oeri’s third volume), areas in which Burckhardt’s ideas showed least his originality.

What now appears as “The Greeks and Greek Civilization” ignores that volume altogether, instead offering key passages (including Burckhardt’s original introductory remarks on method) from volumes one and two on mythology, the polis or city-state and “General Characteristics of Greek Life,” while reprinting volume four, the oddly titled “Greek Man in His Historical Development,” almost in toto.

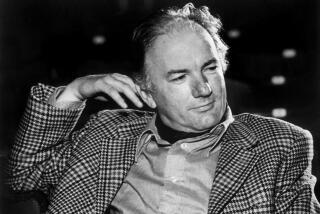

What are we to make of this? The editor, Oswyn Murray, Oxford don and an expert on early Greece, has long wanted to bring the Griechische Kulturgeschichte--or, to be more accurate, some of it--to an English-speaking audience. The original impulse for the project came from M.I. Finley, the famous Cambridge social historian. This explains a lot. After Finley’s death in 1986, Murray joined forces with Sheila Stern, whom Finley had tapped as translator and who has rendered Burckhardt’s rather heavy German into English, distinguished by its style and clarity. The final result of their collaboration is the present volume, which goes all out for Burckhardt’s revolutionary concept of historiography, in particular his radical rejection of positivism--the emphasis on specific facts and dominant political or military figures--in favor of the more abstract interplay of cultural forces. The trouble is, of course, that though this volume is useful, a study minus literature and the arts hardly (to put it mildly) qualifies as kulturgeschichte. What we have here is, in fact, social history (given a misleadingly progressive twist), tempered with historiography. As long as readers realize just what they’re getting--and not getting--it’s a bonanza.

What for many will be most striking is Burckhardt’s flat, and almost unique, refusal to buy into the rose-tinted romantic view of Hellas so popular throughout the 19th century and still around today. Critics also chided him for ignoring not only recent scholarship but also the newly investigated testimony of inscriptions and papyri. Burckhardt preferred to read what the Greeks themselves wrote and in that record found a nation of chronic liars, traitors and vengeful egotists whose main occupation was fighting one another. He saw Delphi, with its rich dedicatory buildings funded from war booty, as “above all the monumental museum of Greek hatred for Greeks, of mutually inflicted suffering immortalized in the loftiest works of art.”

Fueling this attitude was his view of Greek religion (of which I wish Murray had kept more of Burckhardt’s original text) as little more than an official state function and Greek morality as essentially secular (no priesthood, no doctrine, no theology and very little in the way of an afterlife). Small wonder, then, Burckhardt mused, that the Greeks should have had that deep and terrible strain of pessimism running through their culture: As is the generation of leaves, so is that of mankind; never to have been born is best; call no man happy before his death. Murray is right when, discussing this, he refers to “the terrible burden of being Greek, their despair of life and their fascination with suicide.” When they weren’t killing each other, they were almost too depressed to live themselves. An exaggeration, sure, but a useful corrective to all that sweetness and light.

It’s worth recalling, in this context that Burckhardt, a middle-aged Swiss professor at the University of Basel, had as his younger classical colleague and close friend that daemon-driven genius, Friedrich Nietzsche. Both were fascinated by Greek pessimism, but it was Nietzsche (ironically, in view of his later slide into madness) who in “The Birth of Tragedy” asserted the power of Dionysiac emotion to glorify tragedy as the triumph of the human will over adversity. Burckhardt, on the other hand, like Schopenhauer before him, saw the Greeks as the source and victims of their own despair, doomed to a life as brief and transitory as a mayfly’s, its beauties all the more precious for their evanescence. If there are foreboding hints here of Spengler, even of Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” and of Nazism generally, that only testifies to Burckhardt’s unnerving, and virtually unparalleled, ability to predict the future course of European history, including the upsurge of totalitarianism. In defeated countries, he said, there would arise Gewaltmenschen, brutal men of power. Like Teiresias, he foresaw it all.

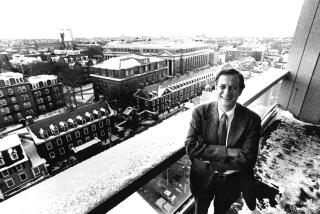

Yet Burckhardt was in so many ways a typical product of his age. He came from an educated patrician family, prominent in public affairs: For a century past, a Burckhardt had always been one of Basle’s two burgomasters. As a young student, he had conceived an adulatory passion for the Germany of Goethe and the concept of idealismus; but for the later Germany of Bismarck and Wagner, of violent nationalism and rampant industrialization, he felt nothing but fear and detestation. In particular, he had that characteristic horror of the masses and mob violence (underplayed, predictably, by Murray) that was so prevalent among intellectuals throughout the second half of the 19th century. Inevitably, all this affected his take on ancient Greece in general and on 5th century Athens in particular.

As an aristocrat and a scholar, he could hardly help but sympathize with the ancient oligarchic suspicion of democracy, something he saw as undermining the educated (oh, all right, elitist) culture to which he belonged. No wonder he feels comfortable with the Plato of the “Republic” and the “Laws,” whose prescriptive yet high-minded authoritarianism was so close to his own world. Yet his sheer originality always takes his arguments way beyond mere crusty conservatism. While gloomy about the loss of idealism in the Hellenistic age, he also tracks, and emphasizes, the period’s increase of individual freedoms. He not only sees but, remarkably, criticizes that stubborn and embarrassing contempt for labor that marks all ancient society. In the archaic period (what he calls the “agonal age”), he singles out for praise the comparative “rarity of war among the Hellenes” at this time. Who else ever thought of pointing out the lack of warfare?

How, one wonders, would Burckhardt react to civilization today? Among his many shrewd aphorisms on the human condition, the following hits home with special applicability: “We can never cut ourselves off from antiquity unless we intend to revert to barbarism. The barbarian and the creature of exclusively modern civilization both live without history.” So much for presentism and the history-is-bunk school. But my own hunch is that he would above all remember, from the more innocent Germany of the early 19th century, Hegel’s famous formulation in the introduction to his “Philosophy of History”: “What experience and history teach is this--that people and governments never have learned anything from history, or acted on principles deduced from it.” If Burckhardt’s arguments cannot dent that massive indifference, the odds are that nothing ever will.