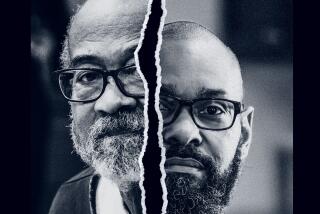

79 Years Old and His Life of Crime Appears to Be Going Strong

- Share via

POMPANO BEACH, Fla. — When Forrest Tucker, at age 73, left prison in 1993, the storied career of this veteran bank robber and stickup man seemed finally over.

He and his wife, Jewell, settled into a comfortable home here on a golf course. He puttered in the yard. He began writing his memoirs, a work he titled “The Can Opener,” which includes an account of his 1979 escape from San Quentin by kayak.

But late last year, a rash of bank robberies erupted within commuting distance of Tucker’s house. And it wasn’t long before the police and FBI zeroed in on a suspect.

The robber was elderly, white-haired and armed.

On April 22, minutes after a masked bandit walked out of a Jupiter, Fla., bank with $5,300 cash, authorities were in hot pursuit. The chase ended on a dead-end street near a schoolyard when the getaway car slammed into a palm tree.

When a police officer ran up and stuck a gun in Tucker’s face, he was dazed, pinned to the seat by an inflated air bag, and laughing. “He looked like he just came off the golf course,” said Broward County Sheriff’s Lt. James Chinn. “You’d more expect to see him go to the early-bird special than robbing banks.”

‘Addicted to the Adrenaline of the Game’

In an age of surveillance cameras, exploding dye-packs and secret alarms, bank robbery is a fool’s game. Most people who stick up banks now are young, violent and desperate, often drug users, said William J. Rehder, longtime head of the FBI’s Los Angeles bank robbery squad. The robbers do little planning, get little cash (an average of $1,000) and have little chance of getting away.

But there was a time when bank robbers were almost folk heroes. Jesse James, John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde were outlaws but also were cheered by some as attacking authority. “Make a run for it, Willie,” spectators called out to Willie Sutton after he was captured in the 1950s.

“Most of these guys have their appetites dulled by the time they’re 50,” Rehder said of career bank robbers. “But [Tucker] was addicted to the adrenaline of the game and couldn’t stop.”

Now 79 and facing an October trial on bank robbery charges, Tucker is being held under tight security in Miami’s federal detention center. Authorities are taking no chances, for Tucker boasts of 18 jailbreaks. He describes himself as being better than Harry Houdini. In pulling off his disappearances, Tucker says, he “had none of the keys and escape materials available to” Houdini.

Tucker “had to do it the hard way . . . [by looking] for the ‘human error,’ which is always the weak spot in even the strongest prisons,” he writes of himself in a letter intended for publishers and movie producers.

Assistant U.S. Atty. Carolyn Bell, who is prosecuting Tucker this time, is a believer. “Mr. Tucker is not simply a career criminal; Mr. Tucker is a career escape artist,” she warned during an April 30 hearing on his request to be released on bond. “He apparently takes great delight in his history and in his ability to outwit and outrun the authorities.”

Said Chief Magistrate Lurana Snow: “Ordinarily, I would not consider a [man his age] a flight risk or a danger to the community. But Mr. Tucker has proved himself to be remarkably agile and resourceful in regard to that.”

Bond was denied.

Tucker’s life of crime, punishment and escape began in 1936, when he was arrested for car theft in Stuart, the central Florida town where he grew up. According to an account in the local newspaper, the 15-year-old used a hacksaw and a chisel that he’d somehow sneaked into the jail to saw a bar off and slip away.

Two years later, he broke into a Miami office and carted off a safe. He was sentenced to 10 years.

That trip to the Florida State Prison launched Tucker on a 40-year tour of some of America’s most notorious penal institutions, including San Quentin, Alcatraz, the Louisiana State Penitentiary and chain gangs in Florida and Georgia. And in each place, he plotted a way to bust out.

For most of three decades--from 1953 until the end of the 1970s--Tucker was jailed in California.

He made one of his most dramatic escapes in 1956 from Los Angeles County General Hospital. While serving time in Alcatraz, Tucker was taken off the Rock for a kidney operation. But as he was being wheeled to the operating room, he jumped off the gurney, knocked down an orderly, fought off two deputy marshals and ran to a parking lot, where he stole a car and drove off. Handcuffed. He was captured--still in his hospital gown--at a Bakersfield gas station five hours later.

In October 1978, Tucker found his way to San Quentin, and in less than a year he had found a way out. Assigned to the prison shop, he fashioned a 14-foot kayak out of wood, plastic sheeting and tape and stenciled the name “Rub-a-Dub-Dub--Marin County Yacht Club” on one side. On Aug. 10, 1979, with the painted side of the boat facing the prison, Tucker and two accomplices paddled toward San Francisco Bay. Tucker waved to a guard on the way by. The guard waved back.

The two prisoners who fled with Tucker were captured within months, but he was not heard from until late in 1981, when he was picked up in Boston in connection with a credit card scam. Before the police knew who they had, however, a woman showed up with the $2,500 bond, and Tucker was gone.

Gray-haired and in his 60s, Tucker settled back in Florida, authorities say, changing his name and blending easily into a community of retirees north of Fort Lauderdale. There he met Jewell Centers, an attractive blond with a comfortable income. They married in 1982.

To Centers, Tucker was a securities broker, often away from home. But according to his memoirs, he only ever had one occupation and over the next two years was busy practicing it in south Florida and the Boston area, where police say he teamed up with another legendary robber, Theodore Green, in what was soon dubbed “The Over the Hill Gang.” The take: more than $1 million in cash and jewelry.

That ride ended in June 1983 when, after tailing Tucker to a meeting with Green in a West Palm Beach parking garage, FBI agents moved in. Green, 68, surrendered. But Tucker slid down beneath the wheel of his car and tromped on the gas, blasting through the phalanx of federal agents and a hailstorm of gunfire.

On a busy street, Tucker abandoned his car and, bleeding from four bullet wounds, commandeered the car of a woman driving by with her two young children.

The chase ended when that car stalled and agents shoved shotguns through the bullet-shattered front window. Tucker had fainted from loss of blood.

At trial, Tucker denied firing at agents. “I could not understand what motive agents would have in saying I had a gun, unless it was embarrassing to shoot a man without a gun.” No gun was ever found.

Sent back to prison in Florida, Tucker also was convicted of other armed robberies in Massachusetts. After one court appearance there, Plymouth County prosecutor Joseph Gaughan commented: “He’ll be 75 years old when he gets out. Hopefully, he’ll no longer have the inclination or the ability to commit the kind of crimes that brought him here.”

A Face Familiar to the Authorities

Those hopes were dashed, said FBI agent Glenda Moffatt, when investigators looking into recent bank jobs spotted the distinctive style of Forrest Tucker. To find him, agents needed to go no further than the Pompano Beach telephone directory.

Minutes after the alarm sounded at the Jupiter bank, Moffatt looked at the surveillance video, which caught the robber with his mask off. The face was familiar.

When the FBI and local police got to Tucker’s home, he was pulling out.

After a 20-minute chase, low-speed by today’s standards, agents found marked money from the bank, a packed suitcase and three loaded weapons in the trunk.

So far, Tucker has refused interview requests, hoping to interest publishers in buying his book, according to Centers. “I love him. I’ll always love him,” she added.

In Stuart, where Tucker was raised, family and friends aren’t sure why the likable, athletic lad they called Woody made a career out of crime. “I don’t know what happened,” said his aunt, Hazel Orman, 90, a retired school librarian. “He slipped up somewhere along the line.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.