The Emotional Pull of Science

- Share via

Scientific research, above all, is supposed to be practical.

That’s one reason certain members of Congress are refusing to fund a modest NASA satellite called Triana that would fix a steady gaze on Earth from space--giving the folks back home an opportunity for real-time, round-the-clock navel gazing.

Unlike other satellites that take patchwork snapshots, Triana would beam back a live image of the whole planet, 24 hours a day. All the planet, all the time, available to everyone through the Internet and cable TV.

“Boondoggle,” House Majority Leader Dick Armey (R-Texas) called it.

“Tripe science,” said Rep. Dave Weldon (R-Fla.).

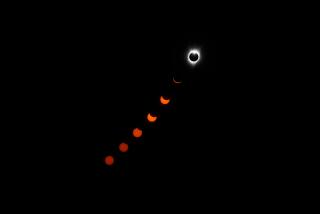

It didn’t help with Republicans that the idea was hatched in the head of Vice President Al Gore, during a dream, no less. The image of our small blue marble floating alone in space, Gore said, would inspire people to take better care of the planet.

But is the purpose of science to be inspirational? Since when is science supposed to be soul food? Isn’t its aim to produce the kind of technology that puts real food on the table?

After all, taxpayers have a right to want their money’s worth. So whenever a new discovery is announced, politicians (and newspaper editors) are forever asking: What good is it? Of what practical use?

Scientists, in turn, have become adept at ticking off practical benefits of even the most esoteric research. During the early days of the space program, we heard a lot about spinoffs like Tang and Mylar. These days, we’re more likely to hear about space-age drugs and computers, or medical imaging technology like PET scans--brought to us courtesy of a particle of antimatter called the positron.

Rarely, however, do people talk about the emotional payoffs of science. Like art museums and national parks, science fills deep philosophical yearnings. One doesn’t have to look far to find these emotional fruits of science. Consider how much our feelings have changed about our place in the universe since Galileo discovered the moons of Jupiter, showing that not everything orbits around Earth; since Newton found that the laws of gravity that make apples fall on Earth are the same everywhere in the cosmos.

No longer could people view the dance of the stars and planets as a performance put on specifically for us. We were part of the action--and a small part, at that.

These days, astronomers tell us that perhaps 90% of the universe is made out of matter completely unlike the stuff that makes up our own world. No one knows the exact nature of this “dark matter,” but whatever it is, it’s alien to us. Or more accurately: We are the aliens in a universe constructed mostly of other kinds of stuff.

Scientists as well as politicians sometimes underestimate the emotional pull of science. The late physicist Frank Oppenheimer--banned from physics by the politics of the McCarthy era in the 1950s--taught high school for some time in the small town of Pagosa Springs, Colo. Teenagers, he thought, would be naturally interested in cars, so he’d take his classes to the junkyard to study the physics of auto parts.

He was surprised, one day, when the students complained. It was all well and good to learn about mechanics, they said. “But we want to know about the stars!”

No doubt, the same yearnings prompted millions of people to stay tuned to their TV sets for days after the adventures of a small rover called Sojourner on the surface of Mars a few years ago. The Pathfinder mission was, above all, a sentimental journey.

Triana, though, has grown up over the past year from a mere dream to a full-fledged scientific mission with a practical job in space. In addition to providing a permanent “mirror” on ourselves, it would keep an eye on environmental shifts and climate changes.

Still, one shouldn’t underestimate the power of dreams. Most scientists, at some level, are dreamers. Practicality can get you to the next step in science. But only dreams can guide the next great leap.

Indeed, last month NASA chief Dan Goldin scolded particle physicists for forgetting how to dream--for being, in effect, too practical. “If we don’t dare to dream, we won’t find anything,” he said in a speech at Fermi National Laboratory outside Chicago. Dreams, he said, are “how the most exciting science happens.”

This sentiment was perhaps best expressed by Fermilab’s own founder, physicist and sculptor Robert Wilson. When Wilson was trying to get money out of Congress to build Fermilab in the 1970s, he was asked to explain the practical purpose of the new accelerator. How would the knowledge that came out of smashing atoms help secure the national defense?

Wilson responded that the new accelerator would have no value in that respect. Instead, he argued, eloquently: “It only has to do with the respect with which we regard one another, the dignity of people, our love of culture. In that sense, this new knowledge has nothing to do directly with defending our country--except to help make it worth defending.”

A lot of scientists would second that emotion.