The Vice Presidential Vise Is Tightening

- Share via

There is a special place in the inner circles of hell that is reserved for sitting vice presidents who aspire to the big chair in the Oval Office, and there is no soul so tortured by this exceptionally cruel form of political flagellation than Al Gore.

The torments suffered by Gore were vividly on display on Monday in Redmond, Wash., when he addressed an audience at the headquarters of software behemoth Microsoft in the aftermath of preliminary findings by a federal judge that the company’s market dominance constitutes a monopoly.

The instigator of the antitrust action against Microsoft is none other than the Justice Department that reports, ultimately, to Gore’s boss, President Clinton. Gore, who extolled the virtues of fair competition, was thrust into the role of the man dispatched to present to the widow of a hanged man a souvenir length of the fatal rope.

Certain elements of Gore’s problems are unique to the relationship between Gore and Clinton, which, by the standard of traditional presidential-vice presidential chilliness could almost be likened to the mythical bond between Damon and Pythias. Certainly no vice president has ever borne so much personal responsibility for vast areas of public policy, ranging from paperwork reduction to global warming.

When such a relationship is cast into the fractious realm of presidential succession, it is bound to suffer. Gore’s dream to succeed Clinton and Clinton’s desire for a legacy that not only extends his policy imprint but also effaces the stain of the impeachment are increasingly at odds.

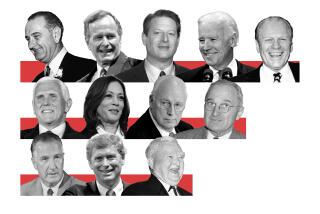

As Gore solemnly lectured the Microsoft employees, a trained ear might have detected the fluttering of the celestial wings of vice presidents of the past who struggled to accomplish the essentially unattainable objective of freeing themselves from the follies of the very administration whose accomplishments were the basis for their own claim on the presidency. In that auditorium in Redmond, one might have discerned the ghostly outline of Vice President Richard M. Nixon squirming uncomfortably while John F. Kennedy pummeled him over the Eisenhower administration’s apparent acquiescence to the Castro regime in Cuba while Nixon knew all along of the secret plan to invade the island. One might also have seen the spectral traces of Hubert Humphrey straining to free himself from the Johnson administration’s failing policy in Southeast Asia, or George Bush in 1988 pleading that he was outside the loop of decision in the arms-for-hostages deal.

Both Humphrey and Bush, while writhing in the toils of unpopular or disgraced policies, sought to take credit for the accomplishments of the presidents under whom they served. It is a tricky path that only the most agile can negotiate.

Gore’s problem is more acute than those of other aspiring vice presidents in that the man who still occupies the presidency is so legacy minded. Neither Eisenhower nor Reagan was especially active in the latter stages of their second terms, and while they bequeathed to their vice presidents political estates that had both beneficial and undesirable elements, they were not so openly competing with their No. 2 men for the attention of the public.

Clinton refuses to relinquish the limelight. Like a performer who fails to notice that his audience is already departing the theater, Clinton continues to bow.

Some difficult moments for vice presidents come about as the result of the usual conflicts that surround the approval of the budget. The apparent surrender of the White House to the demands of House Republicans that abortion advocacy be muzzled as the price for the U.S. ponying up its United Nations dues is the case in point. Unhelpful, from Gore’s point of view, was Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s offering herself up to take the heat for the Clinton administration’s failure to back abortion rights advocates to the hilt in the struggle over the U.N. dues. For Gore, the ideal outcome would have been a White House willing to face down the GOP and cause them to suffer the opprobrium of being responsible for this country being voteless in the world body. Clinton instead opted for a settlement over a statement.

Still, should fortune favor Gore in his quest for the presidency, the person with whom he shares the ticket in 2000 should have no expectations that Gore’s experience with Clinton will grant him more vice presidential running room if he tries to succeed his boss. For presidents, paradoxically, the impulse to be revered by posterity is more intoxicating than the political needs of the person best positioned to advance that goal.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.