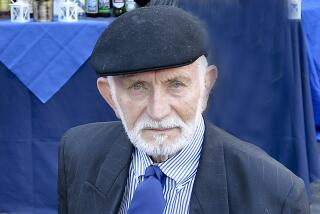

John Stapp Dies; Onetime ‘Fastest Man’

- Share via

John Paul Stapp--heralded as “the fastest man on earth” after his daring, high-speed ride on an experimental rocket sled in 1954--has died in New Mexico after decades of research to improve transportation safety. He was 89.

Stapp, a medical doctor and retired Air Force colonel who died Nov. 13 in Alamogordo, spent much of his life preaching that even when people are subjected to extreme forces, like those in high-speed traffic accidents, better safety equipment can prevent lethal injuries.

He knew what he was talking about.

On Dec. 10, 1954, in an Air Force test to study the effects of bailing out of airplanes at supersonic speeds, Stapp was belted into the seat of an open sled equipped with nine rockets, each capable of producing 4,500 pounds of thrust.

The rockets blasted for five seconds, accelerating him from a standstill to 632 mph--fast enough to outrun a .45-caliber bullet. But that was the easy part.

An instant later, water brakes slammed the sled to a dead stop in just 1.4 seconds.

“My eyeballs pushed against the upper lids, pulling at their attachments with a searing pain like a dental extraction without anesthetic,” he wrote later. “I had crashed to a stop, a crash lasting 18 times longer than that of a car hitting a wall at 60 mph.”

Stapp realized that he could not see the attendant unstrapping him from the sled.

“With no emotion, as though I were an onlooker, I thought: ‘This time I get the white cane and the seeing-eye dog,’ ” Stapp wrote.

But by the time he got to the hospital, Stapp realized that the belts that lashed him to the sled had prevented serious injury. His sight returned, and except for two black eyes, he was in good health.

The sled run ended the argument over whether seat belts could save lives. With his aviation tests completed, Stapp turned his energies toward the automotive industry.

In 1955, he invited experts from the Society of Automotive Engineers to review the sled tests. Two years later, Volvo became the first automotive manufacturer to install seat belts in cars.

In 1966, during a brief ceremony in the White House rose garden, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law a measure requiring seat belts on all new automobiles sold in the United States. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader was the star of the show. But Stapp, a rather paunchy, unprepossessing man who stood on the sidelines, was the real hero.

Born in Bahia, Brazil, to two Baptist missionaries, Stapp worked his way through college, earning a PhD in biophysics from the University of Texas and a medical degree from the University of Minnesota.

Money was scarce during Stapp’s college years. So scarce, according to a longtime friend, Charley Barr of Rancho Palos Verdes, that Stapp was reduced to dining on some of his laboratory specimens.

“He insisted that guinea pigs are quite delectable when cooked in a laboratory oven,” Barr said.

In 1944, at the height of World War II, Stapp joined the Army Air Corps, soon specializing in studies to determine the effects of ever-faster flights--and bailouts--on the human body.

Published reports state that one of the early experiments inspired what became known as Murphy’s Law.

According to the reports, one of Stapp’s assistants, Capt. Edward A. Murphy Jr., rigged a harness incorrectly. As a result, sensors designed to measure the strain to which Stapp was subjected during an early sled ride failed to register.

Hence the maxim, paraphrased a dozen ways: “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.”

In 1947, Stapp was assigned to the Air Corps base at Muroc Dry Lake in the Mojave Desert--an installation now known as Edwards Air Force Base--where a cocky young pilot named Chuck Yeager was about to become the first man to break the sound barrier.

A few months later, about the same time that the Air Corps became the Air Force, Stapp’s tests were moved to Holloman Air Force Base, near Alamogordo.

The first sled rides along a track skirting the White Sands National Monument were not as fast as his subsequent record run, but they were still daunting. Acceleration and deceleration forces rose to 45 times greater than gravity, driving Stapp’s apparent body weight from its normal 170 pounds to 7,650 pounds.

He suffered a concussion and an abdominal hernia, and broke several ribs, his coccyx and--twice--a wrist.

“I set that myself,” he said later.

The record sled ride on Dec. 10, 1954, was Stapp’s 29th, and his last.

During a test about a week after that historic run, the sled came off the track at more than 600 mph, tumbling end over end across the desert. Fortunately, it had been a dry run, with no one on board.

After that, the sled runs were made with dummies and animals as passengers. One in 1957 reached 1,335 mph.

With his sled runs over, Stapp decided it was safe to marry. In 1958, he wed Lillian Lanese, a former ballet dancer.

He threw himself into the auto safety campaign as wholeheartedly as he continued to pursue aviation safety. In 1959, he traveled 170,000 miles and delivered 225 speeches.

For motorists, his research helped pave the way for padded dashboards, better bumpers and, of course, mandatory seat belts. For aviators, he assisted in the design of better seat belts and shoulder harnesses, improved escape mechanisms and stronger cockpit frames.

He served as a consultant for the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics.

Among his many awards are the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Service Medal and the presidential Medal of Technology.

Stapp leaves his wife and a brother, Wilford.