Ulster Party Vote Breaks Deadlock in N. Ireland

- Share via

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — Overcoming decades of hatred and deep internal divisions, Northern Ireland’s largest Protestant political party decided Saturday to back a compromise deal to set up a power-sharing government with Roman Catholics before the Irish Republican Army begins to disarm.

The Ulster Unionist Party council’s vote clears the way for Northern Ireland to establish its first provincial government in more than a quarter-century.

Parties in the Northern Ireland Assembly are expected to name a 12-member Cabinet on Monday that would assume powers from the British government before the end of the week.

The Ulster Unionist council’s vote is a triumph for party chief David Trimble, who is to become first minister of the new provincial government. Trimble forged the compromise with Gerry Adams, leader of the IRA’s political wing, Sinn Fein, and then put his own leadership on the line seeking the support of unionists.

To do so, Trimble in effect gave Sinn Fein a deadline of two to three months to convince the IRA to begin getting rid of its weapons. He promised the 858-member council a chance to vote on the deal again in February and told it that if the IRA had not started disarming by then he would resign as first minister and pull the party out of the government, in which Sinn Fein will have two members.

Trimble won the vote and threw down the gauntlet to the leader of Sinn Fein.

“This clears the stalemate we have had in terms of the process,” Trimble said. “Now, we’ve done our bit. Mr. Adams, it’s over to you. We’ve jumped. You follow.”

Adams said Trimble’s ultimatum went beyond the terms of the compromise painstakingly crafted during five weeks of negotiations with U.S. mediator George J. Mitchell.

“It is, in my opinion, the wrong way to sort this matter out,” Adams told BBC radio. “It will fuel the uncertainty, and it will also keep alive the hope of the rejectionists [of the peace process] inside and outside the Ulster Unionist Party.”

Many unionists do not believe that the IRA intends to get rid of its weapons at all. They see the agreement as a con by the republicans to get into government while keeping a private army to enforce their will.

Others suggest that Sinn Fein might be sincere about trading bullets for democratic politics but that it does not have the clout to persuade the IRA to disarm. Few unionists say they are convinced that the peace process will work, although many are willing to give it a try.

In Washington, President Clinton hailed the unionists’ vote.

“Government in Northern Ireland is being put back directly in the hands of all the people,” Clinton said in a statement. “I welcome this progress and urge all parties to continue working together on building the foundations for lasting peace.”

Northern Ireland’s pro-British unionists, the vast majority of whom are Protestants, and the minority Catholics who want to be united with the Republic of Ireland signed a peace agreement in April 1998 calling for the establishment of a regional government with Sinn Fein in exchange for the disarmament of paramilitary groups such as the IRA.

The accord was overwhelmingly endorsed by Protestant and Catholic voters, but until now neither side had been willing to take the first step.

The British, Irish and U.S. governments had all pressed Trimble to abandon his “no guns, no government” policy and test Sinn Fein’s commitment to end 30 years of bloody conflict--to, in essence, call the republicans’ bluff. But after days of intense talks with the British and Irish prime ministers in July, Trimble refused, and the so-called Good Friday peace agreement appeared on the verge of collapse.

Mitchell, who had brokered the original agreement, was called back in September. Under the deal he hammered out with the two sides, Trimble agreed to form a government with Sinn Fein in exchange for a public commitment by the IRA to name a senior member to an international commission on disarmament.

The IRA representative would be appointed on the same day the Cabinet took power, and disarmament would be completed by May 2000, according to the terms of the Good Friday accord.

But the fate of the step-by-step compromise was entirely in the hands of the Ulster Unionist council, and Trimble was by no means guaranteed their support going into the closed-door meeting in Belfast on Saturday morning. If it fell, he fell.

Six of the 10 unionist members of the British Parliament already had declared their opposition to the deal. The council, made up of independent-minded farmers, homemakers, small-business owners and local politicians, was seen as highly unpredictable.

Trimble decided to hold the meeting at the modern Waterfront Hall, on the banks of the cleaned-up Lagan River, instead of at the faded Victorian Ulster Hall, where key party decisions always have been made. He wanted to make the point that this $56-million convention and performing arts center, built in 1997, and the skyscraper cranes working around it on peacetime construction projects were the way forward. The message: Peace brings prosperity.

According to delegates, the three-hour debate was highly emotional, with 27 people speaking for or against the motion that Trimble put forward to allow him to proceed until February.

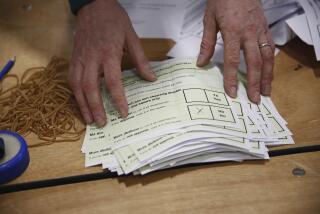

The final vote was 480 to 349, about 58% in Trimble’s favor. It was short of the two-thirds majority that Trimble’s camp had hoped to get but enough to declare victory over opponents in his divided party.

Key to his success was the support of his deputy, John Taylor, who originally spoke out against the deal but came around in the eleventh hour.

Taylor, who survived an IRA machine-gun attack in 1972, was instrumental in bringing down the last unionist leader who tried to form a power-sharing government with Catholics in 1974. Brian Faulkner was ousted from the party at a council meeting like Saturday’s. He managed to set up a Cabinet as an independent unionist, but unionist workers declared a provincewide strike and the government collapsed in just four months, along with Faulkner’s political career.

Trimble was determined that Northern Ireland’s history should not repeat itself. In a speech described as thoughtful and well crafted, he told the delegates that they would never get a better opportunity to bring the armed conflict to an end. Then he said he had given the party president a letter of resignation as first minister to hold in the event disarmament had not begun by February.

His lieutenant, Ken Maginnis, told the crowd that a no vote would likely mean isolation for Northern Ireland’s unionists. The British, U.S. and Irish governments would wash their hands of them, delegates recalled him saying.

“This is the lesser of two evils, and we’ve got to give it a try,” said Tom Davison, 83, a delegate from Bangor who said he made up his mind after listening to the speeches. “The leader of the party was quite right to change the policy. It’s no good holding on to the old line when events overtake it.”

But the dissenters were angry and vowed to keep on fighting. As he left the building after the vote, Maginnis was accosted by irate unionists shouting, “Go die!” and “You sold us out!”

William Thompson, an Ulster Unionist member of the British Parliament, said he will resign from the party this week when a provincial government is formed.

William Ross, another member of Parliament opposed to the deal, said he will stay in the Ulster Unionists and “fight, fight, fight until this party comes to its senses.”

But Trimble, appearing with his party chairman and beaming wife after the vote, seemed confident that the Ulster Unionists had done the right thing.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.