A Dose of Mercy

- Share via

SANTIAGO DEL ESTERO, Argentina — Mercedes Paz tries to make herself invisible. Head tucked down, hands covering her twisted mouth, body curled inward, the 18-year-old sits on a roughhewn bench in the waiting room of this medical outpost.

Like others at the clinic, she waits to be able to eat and breathe easier. To have a smile.

They wait to be seen by a team of medical volunteers who have just arrived in this remote northwest corner of Argentina. The vast majority of the patients are children who, like Mercedes, have congenital deformities affecting the mouth and face, conditions that would be repaired routinely in infancy in the United States.

If he could, Newport Beach plastic surgeon Michael Niccole would mend them all, one by one. But in 10 days, there won’t be time, even with the international team he assembled of more than 30 surgeons, anesthesiologists, pediatricians, nurses and support staff to work at the rudimentary regional hospital nearby.

Niccole’s team--with the help of more than three dozen volunteers from this city of 200,000--will see a steady stream of patients, 204 in all. For nearly every patient who is treated, another must be turned away. By the time the team leaves in early June, it will have performed 151 surgeries on 106 patients, most of them young children.

The surgical team is one of numerous humanitarian missions organized each year to bring medical care to poor or geographically isolated parts of the world. Many focus on repair of cleft lip and palate, conditions that occur worldwide, but strike especially often in South America and parts of Asia. There, the incidence can be as frequent as one in 500 births, double the number found in other countries.

Each mission requires international cooperation and the support of many individuals and local community groups, and often the driving force of a team leader. On this trip, that person is Niccole.

In this work, he says, there is “gratification you don’t get in your office. . . . You know you won’t get anything in return except hugs or tears, or maybe a fresh mango.”

Most of the people in the waiting room in Santiago del Estero heard about the medical team’s visit through doctors and public service announcements months in advance. They have arrived on foot and by bus. Those who will have surgery will stay with their families in a nearby barracks to recuperate, most for a few days before a departing checkup to remove stitches.

Often, the children’s lives evolve as Mercedes’ has. She dropped out of school in the third grade because she was ashamed of her face--a cleft lip and crooked teeth protrude from her malformed mouth. Her speech is so impaired she rarely tries to speak. She doesn’t have a palate, so she suffers when she eats, often choking and gasping for breath.

The disfigurement has made her a recluse, isolated even from her family. At home, she takes her meals alone so no one can see when she is unable to swallow her food.

A Change of Pace

for the Surgeon

At home, the kind of surgery Niccole performs is usually elective--procedures such as face lifts and breast implants. He is the founder of CosmetiCare, a plastic surgery center that has grown and prospered in the Southern California climate. As he built his practice, though, the 54-year-old father of four donated time and expertise to those who could not afford needed reconstructive surgery--the less publicized, less glamorous side of plastic surgery.

Niccole grew up in Huntington Beach and studied medicine at UC Irvine. His volunteer medical work began in the early 1980s with the Santa Clara-based “Flying Doctors.” Once a month, he would hop a twin-engine plane with other surgeons and head for backwater towns in Mexico. There they would repair deformities and treat injuries that might otherwise doom children to lives as outcasts.

Later, Niccole joined the World Health Organization on similar mercy missions to Alamos, Mexico. And by 1987, he created the Magic Mirror Foundation, a nonprofit program providing free reconstructive surgery for scores of low-income patients across Southern California.

But this mission to Santiago del Estero, the second for Niccole, was financed and supported by Rotaplast, an offshoot of the Rotary service club. The $80,000 tab, most of it for transportation costs, was split between U.S. and Argentine Rotary groups.

Rotaplast was organized five years ago to support international medical missions and has sponsored volunteer teams primarily headed for South America. Nine missions already have been financed for September 2000--including another to Santiago del Estero.

Other medical relief organizations that help people with congenital facial disfigurements or who have suffered burns or other injuries include Operation Smile, which sponsors 60 missions a year, and Interplast, which does about 40 a year. All are staffed with volunteers from the medical community--including many plastic surgeons.

Niccole’s first trip to Santiago del Estero came last year at the urging of colleague Hooton Michael Daneshmand, a partner in his Newport Beach practice. Because so many patients had to be turned away on that trip for lack of staff and time to help them all, Niccole decided to return this year as head surgeon.

It took him more than six months to recruit the players for the surgical team, which includes doctors from Canada, England, Germany and the United States. Among them is plastic surgeon Amy Bandy of Irvine, who has offices in Newport Beach and the South Bay.

The work is intense in Santiago del Estero. But team members say Niccole lights up the operating room with his energy.

“Niccole shoots from the hip,” said Tom Elwood, an anesthesiologist from Seattle. “He’s a decisive, go-for-it kind of person. He’s a classic. He decides what he wants to do and does it, and that makes him so good. He can walk into a room and take over.”

“He works like a dog, but his operating room is like a party,” says Daneshmand, who joined another team this summer. “He’s the wild one.” Niccole’s music of choice while wielding scalpel and clamps: vintage Rolling Stones.

Long Days and

Many Challenges

In Santiago del Estero, the team’s base of operations is the largest hospital in the region, but it still is a facility with limited resources. When the one X-ray machine breaks down, it stays down until a technician can fly in from Buenos Aires to fix it.

The surgical team starts each day before dawn and works until 7 or 8 p.m., long after the Argentine autumn sunset. They bunk for the night in a rundown hotel about 10 minutes by bus from the hospital.

Niccole does much of the surgery himself but also oversees and trains others, including two Argentine surgeons. When local doctors feel confident that they are able to take over future work, Rotaplast will move on to other regions in need of surgical teams.

Working with outdated hospital equipment is especially trying for the anesthesiologists, who have to rely on machines with broken dials and missing safety features. Before the mission is over, the old equipment will nearly cost an infant’s life.

Leonela Angela Castro, at 26 days, is younger than most babies who undergo surgery. Given the severity of her eating and breathing difficulties caused by a split in both her lip and palate, waiting a year for another team seems the riskier option. They decide to stitch together the lip for now and deal with the palate next year.

During surgery, though, she develops difficulty breathing. The barely functioning monitoring equipment fails to pick up her distress--distress that may have been triggered because a vital tube doesn’t fit the equipment properly. When Niccole recognizes the baby’s failing condition, he quickly finishes repairing her palate and rushes her to recovery.

Through one anxious hour, team members work to stabilize the baby. Niccole worries that he might, for the first time in his career, lose a patient. She is given oxygen, swaddled in blankets and placed in one of the hospital’s few incubators, and nurses monitor her through the night.

By the next morning, Leonela is nursing at her mother’s breast for the first time in her life. Several days later, the Castro family is able to leave for home with a healthy child.

Graciela Brovo, a university medical student from Santiago del Estero and a Rotarian volunteer in the barracks, is, like everyone else, relieved and pleased that the infant has pulled through.

“When she is grown up, she won’t have shame,” Brovo says. “This will change her future. She will grow up to be a normal child.”

Carrying the Scars

of Her Disfigurement

Mercedes Paz’s family had saved for a year for the $30 round-trip bus ride from El Churqui, where they live in a concrete-floor home without plumbing or running water. Mercedes was born seventh in a family of 11 children. Her father is a day laborer. If he doesn’t work, the family doesn’t eat.

In the waiting room, she is intent on not having anyone notice her.

“When I saw her, her personal space was yards larger than anyone else’s,” recovery room nurse Barbara Brooks of Maine said. “I knew we could make her complete. But would this validate her? So many of the kids are younger and we can get to them before they’re emotionally scarred.

“Unfortunately,” Brooks adds, “people are so cruel and treat kids with deformities like they are possessed by the devil.”

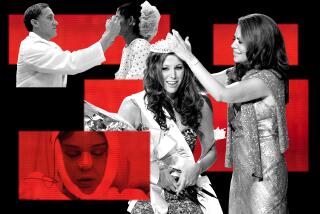

It may be too late to influence Mercedes’ childhood, but surgery remains a chance of a lifetime. In a 3 1/2-hour operation, Niccole repairs the girl’s mouth, nose and palate.

At her age, Mercedes may never learn to speak normally, a problem for many older children who undergo cleft palate surgery. But Niccole says she should be able to eat and breathe more easily. And, as she realizes that she looks, for the first time, very much like everyone else, Mercedes may gain the confidence to show her face, he says.

Mercedes and her family are very thankful. The trip to Santiago del Estero has turned out well. More than a week after the surgery, Niccole visits the Paz family at their home in El Churqui, about three hours away.

Niccole’s reward is a feast of fresh chicken and empanadas.

And a smile from Mercedes.

Gail Fisher can be reached by e-mail at gail.fisher@latimes.com.

The Story Continues: Additional photos and video clips of Dr. Michael Niscole’s work in Argentina are on The Times’ Web site: https://www.latimes.com/smile

About Cleft

Lip and Palate

Cleft lip and palate are congenital defects that occur very early during fetal development, usually five to nine weeks after conception.

A cleft lip is a separation of the two sides of the lip. A cleft palate is an opening in the roof of the mouth that occurs when the two sides of the palate do not fuse. Some children have both disorders.

A majority of clefts appear to be caused by a combination of genetic, nutritional and environmental factors. The incidence is higher among those who have a history of cleft in their families, among mothers who smoke heavily and among those who lack folic acid in their diet.

Incidence varies by region and country, generally from 1 to 2 per 1,000 births.

More information

Cleft Palate Foundation

Chapel Hill, N.C.

(800) 24-CLEFT

https://www.cleft.com

Surgical Missions

Here are several of the largest international volunteer medical organizations that aid children with cleft or other disfigurements.

* Operation Smile

Norfolk, Va.

(757) 321-7645

https://www.operationsmile.org

* Interplast

Palo Alto, Calif.

(650) 962 0123

https://www.interplast.org

* Rotaplast

San Francisco

(415) 538-8120

https://www.rotaplast.org

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.