Wrestling With a Monster

- Share via

LONDON — In 1878, when Sir George Grove, a London musician, editor and founder of the Royal College of Music, published the Grove Dictionary for Music and Musicians, it was four volumes long. By 1904, the second edition was five, a size that held through the third (1927) and fourth (1940) editions. The fifth printing, in 1954, was an expanded nine volumes. And in 1980, under the editorship of former Times of London music critic and scholar Stanley Sadie, the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians had more than doubled in size, weighing in at 20 volumes. By this time, the dictionary had become the world’s definitive music reference resource, relied upon by scholars and schoolchildren alike for its scope, authority and accuracy.

In 1996, when Sadie began commissioning stories for the second edition of the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, or New Grove II as the editors are calling it, he asked some of the 6,000 contributors--mostly top scholars worldwide--to update, fill in gaps, refresh what was there. But when the copy started rolling in a few years later, Sadie says, it was not uncommon that assignments of 500 words, for example, came in at 3,000. Contributors found that simply freshening existing text wasn’t sufficient after a publishing break of 20 years.

While Sadie calls the New Grove II a revision of the 1980 version, he acknowledges that most of the biographies have been rethought and rewritten, including new research and perspectives even on artists as established as Strauss or Chopin, Bartok or Tchaikovsky. Companion lists of a composer’s works have been reexamined, and bibliographies that accompany each entry have been expanded and rethought.

There are, for example, 2.3 million words on Baroque composers alone. In addition to biographies of composers, performers and music writers, Grove contains articles and entries on musical styles, terms, genres, ancient music, church music, instruments and their makers, performance practice, printing and publishing, world music, pop, jazz, concepts and acoustics, to name a few. The editors estimate that of the dictionary’s nearly 30,000 articles, about 5,000 are new.

What’s more, historical and societal changes opened up areas of interest and possibility. “We’ve changed the balance to reflect the way the world has changed,” Sadie says. The fall of communism has meant that scholars from former Eastern Bloc countries “can write the truth without fear or censorship,” he says. It’s also made it a lot easier to phone and fax and have meetings with scholars in that part of the world.

The largest area of expansion is that of 20th century music. “We’ve had quite a bit more of it,” he says, adding that 3,000 serious composers were featured in the 1980 version; this time there are 5,000. There is strengthened emphasis on non-Western and world music, including new articles on traditional indigenous popular music of cultures worldwide, popular and music theory issues such as the philosophy and psychology of music, borrowing, feminism, women in music, postmodernism, deconstructivism, gay and lesbian music, social realism, Nazism, nationalism, and the relationship of computers and music.

When the New Grove II becomes available at the end of January, the anticipated 24-volume version will, in fact, be a whopping 29 volumes, or about 25 million words. “I think what was thought of before as a sort of replacement, updating of Grove is something that is now almost as new as the last New Grove,” says John Tyrrell, executive editor of New Grove II.

“Grove is a huge financial and human and technical investment,” says managing director Ian Jacobs, “to manage the money and to explain to our shareholders why we should be spending this kind of money, and since it always runs over budget, why we couldn’t help running over budget. And since it always runs late, why it couldn’t help running late.”

But if running late and long and over budget have been constants in the 120-year-long history of publishing the Grove, this time around, the staff of the Macmillan-published dictionary has had a whole new set of obstacles to face: how to put the world’s oldest music reference, a publication with a 20-year lead time, online.

*

While the function of Grove in the Internet era might be the leading question on the minds of the Grove staff, at this stage in the operation, on a midsummer afternoon earlier this year, what’s left of the once 60-member editorial team is concerned with such old-school tasks as checking page numbers and captions, making runs to the British Library to verify titles of ancient manuscripts and marking up piles of page proofs--printed on paper and marked in pen--to be sent to India to be keyed in, returned and checked again.

“I’m sure it will change gradually, but there is something reassuring about having that little piece of paper in front of you,” says publishing director Laura Macy, running her hand over a stack of page proofs piled in a bookcase in Macmillan’s offices in central London.

The editorial process has been largely overseen by Tyrrell, an old friend of Sadie’s who worked for three or four years in the 1970s as a desk editor for the last edition, taking time off from his teaching job at Nottingham University. By the time he’d decided to take Sadie up on his offer to handle the day-to-day editing of New Grove II, it was 1997. The articles had been commissioned, the last edition surveyed and scanned for reuse.

“It was psychologically quite difficult to move over from the commissioning to the editing,” Tyrrell says. As a desk editor the last time around, he says, he’d noticed that members of the staff, a mixture of bright young graduates and PhDs, many without editorial backgrounds, tended to do things their own way, leaving the fine-tuning to a couple of purse-lipped top editors at the end of the process.

“You found you had 40 editors and 40 house styles,” he says. To build consensus, Tyrrell says, he “did what I know best, which is teaching.” He devised a three-week editing course based on Grove’s in-house style bible, a 200-odd-page document with answers to editorial conundrums big and small: abbreviations for oft-quoted journals; rulings on which way to go on a word that has been italicized 21 times and not italicized 20 times; standards for defining nationality in the wake of changing political geography.

Tyrrell also started wrestling with issues raised by new copy. One of the most significant changes from the last edition was that contributors were suddenly pumping up formerly selective bibliographies by downloading comprehensive lists from the Internet. Not only was this a space problem for the printed edition, but it raised yet another question about the role of Grove, which has always been to screen and select, to advise and guide.

“Space is not an issue in terms of the Internet,” Tyrrell says, “but it is in terms of editorial control. I as a scholar feel quite uneasy about having a very minor composer on whom someone has devoted his or her life work, and therefore writes an article on this tiny, obscure 17th century Italian composer, which is as long as Bach. That offends me.”

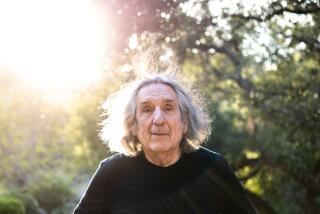

The question of how Grove will learn to adjust to the needs of the Internet, to remain selective while giving in to the demands of users who are accustomed to a more-is-better approach to research, is one that much of the staff who worked on putting out the New Grove II won’t be around to answer. Tyrrell planned to leave for a new professorship in Wales at Cardiff University in the fall, to teach and work on a biography of Janacek. After 30 years as editor of Grove, Sadie, who turned 70 in October, planned to retire within the year. He is looking forward to having time off and a chance to write his own books, he says, but he also admits his decision has everything to do with not having the answers to Grove’s Internet future.

“It’s a very difficult question to answer,” he says. “But it’s the central question for the future. That’s why I’m quite glad I’m leaving it to a younger person.”

*

Sadie’s replacement has yet to be named. But one person who is sticking around is managing director Jacobs, who began his career selling Grove around the world in the 1970s. As the United States has always been Grove’s largest market--it accounts for between 50% and 60% of total sales--Jacobs set up a Washington, D.C.-based office for four years beginning in 1976, where he learned about direct mail, an American marketing strategy that would prove highly successful for Grove, a product that then cost $1,500 and has never been sold in bookstores. Jacobs says that by the time the New Grove II is released, Macmillan will have spent about $30 million. Jacobs is now responsible for making financial sense of a new business model that includes a combination of print and online sales for individuals and institutions. Individuals should expect to pay about $300 a year for online access; the hard-bound, 29-volume set costs about $4,000.

“We’ve always been a historical resource, and we’ve never claimed to be up-to-the-minute, and it’s never mattered,” Jacobs says. “Now users expect us to be much more up-to-date than we used to be, but they’ve also figured out it’s not an easy job. They say we want it up-to-date, but we want you to maintain your standards and we’re worried about how you’re going to do that.”

At this point, no one seems to have an answer. But Sara Lloyd, executive producer of the online version, says she is confident the Grove brand will be a benchmark of quality in a murky sea of music content on the Web.

“Every Tom, Dick and Harry has a site on Mozart if they’re a fan, or a modern band like the Eurythmics,” she says. “What Grove should still do on the Web--which is no different to what it’s done always--is to be this protective strainer for what’s really important.”

Lloyd points out that just as a fashionable group of organists or avant-garde composers might drop out or get repositioned from one print edition to another, entries that fall out of fashion or shift in importance will remain in the archives--in that infinite cache of cyberspace. “I think we will find that we put somebody into the online version because they’re significant at that period,” she says, “but then two years later or six months later, we might take them out again.” A permanent in-house editorial team will provide quarterly updates and supervise the annual review of a major area of interest.

The indisputable advantages to Grove online will include a search engine that will make it possible to search all 25 million words in a heartbeat; quick cross-referencing and links, plus networked systems for libraries where students formerly had to share one copy. And in a world where many people don’t sight-read music, “sound illustrations” will begin to replace excerpts from scores for some of the articles, thanks to partnerships with CD labels and university archives.

Tyrrell says he is worried about potential conflicts of interest between commercial links--say to record or music-publishing companies--and the competing interests of musicologists and scholars, but Lloyd insists that the commercial links will be as educational as possible, heavily information-based rather than promotion-based and will include multimedia elements that illustrate content. Such links, she said, will appear in the free areas of the site--which will include industry news, reviews, events listings and forums--leaving the costly reference area free of advertising.

The online version will also include interactive, rotating 3-D illustrations to show what a gamelan looks like, or how the wind moves through a trumpet, or the physics of acoustics. Before, such information was relegated to words and a complex line drawing.

Publishing director Macy is an American musicologist who came to Grove in 1997. She says that while she is excited about the move to the Internet, it makes her scholarly heart a little nervous to think of experts rushing to make deadlines, instead of thoughtfully taking the years it sometimes has taken them to weigh in. “If you can write it all down and publish it in 20 volumes, that feels definitive,” she says. “But the Internet just points out the elusiveness of what we think of as definitive. I think it is the question facing editors of this kind of thing. It’s one I can’t answer, but I think about all the time.”

Looking around at stacks of papers and shelves of books in the quiet rows of cramped cubicles in the Grove offices, one can’t help but feel that all these pieces of paper, covered in check marks and red and green ink, numbered and shelved and stored for years, give the rather ephemeral business of writing a kind of footprint, some tangible evidence of work produced by all the people who have poured their minds into making this. At this moment, it’s hard to imagine that the editors of Grove will still be making red-ink check marks and storing their page proofs in warehouses in 20 years, when the next edition should be due.

“I for one would not like to swear that in 20 years, we’ll do another book,” Lloyd says. “It might be that we create smaller books on specific subjects or do another print version before 20 years, because we have capability. Twenty years is a long time in the Internet world.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.