New Class of Anti-HIV Drugs Shows Promise

- Share via

SAN FRANCISCO — Researchers Monday reported preliminary success with a new class of anti-HIV drugs that works against viruses that have developed resistance to other AIDS medications.

New classes of drugs are crucial to future therapy because, although 14 AIDS drugs are now in use, as many as 40% of HIV-infected patients carry viruses resistant to them.

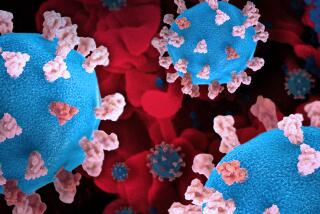

The new drugs, called entry inhibitors, act by a completely different mechanism from existing AIDS drugs. Rather than interfering with viral enzymes like existing drugs, they block the entrance of the virus into cells.

Researchers from Trimeris Inc. reported here Monday that the first of these new drugs, called T-20, has controlled viral replication for as long as 36 weeks in the first patients treated with it, although the drug has to be injected twice a day. They presented their findings at the seventh Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

“The major excitement is that this has shown conclusively that [entry inhibition] works,” said Dr. Robert T. Schooley of the University of Colorado Medical Center. “This will launch a feeding frenzy of development by pharmaceutical companies to find small molecules that can be given orally to do the same thing.”

Researchers reported Monday on two other types of entry inhibitors that are in much earlier stages of development. And just last week, a team from Merck said it had found the first potential members of a completely different class of drugs called integrase inhibitors.

“I think we have valuable new tools with the new classes of drugs,” said Dr. David Ho of the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center. T-20, especially, is “as powerful as the protease inhibitors” that revolutionized HIV therapy when they were introduced in 1995, he said. “But it will take another year to determine what their role will be clinically.”

The existing classes of drugs--reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors--block the action of two enzymes that HIV uses to take over cellular metabolism once it has invaded its target cells. Drugs that block their activity thus have to get inside the cells as well. Once inside, they can produce a variety of annoying side effects that often have made compliance with drug regimens difficult.

The entry inhibitors, in contrast, prevent the virus from entering the cell in the first place. Because they don’t have to get inside the cell, scientists suspect that the drugs are less likely to produce adverse effects. And indeed, they have found that the primary side effects of the drug are rashes and swelling at the injection site.

Entry to the cell proceeds through two distinct steps. The virus first must bind to the target cell, using one of two receptors, called CCR5 and CXCR4. Two of the new inhibitors target this step.

In the second stage, the membrane that encapsulates the viral genetic material must fuse with the membrane of the target cell. T-20 is directed at this step, and is thus called a fusion inhibitor.

T-20 is a peptide--a protein fragment--that initially was isolated from an HIV protein, but now is produced synthetically. Because peptides taken orally are destroyed in the stomach, it must be administered by injection under the skin.

Its developers thought that the need for injections would present a problem with compliance, said Dr. Sam Hopkins of Trimeris. But checking blood levels in the several dozen patients already treated showed, “surprisingly,” that patients in the studies were taking it regularly, he said, perhaps because other drugs were no longer helping them.

T-20 has now been given for more than 32 weeks to a group of patients who had been heavily treated with other AIDS drugs and were no longer responding well.

The drug reduced HIV concentrations by tenfold to a thousandfold, Hopkins said. As viruses replicate in the body, they spread from cell to cell to maintain the infection. Virus particles halted by T-20 are cleared from the body. Moreover, levels of crucial CD4 cells (the immune cells attacked by HIV) were continuing to rise even at 32 weeks.

The company now is testing it in patients who have used protease inhibitors but not reverse transcriptase inhibitors and in patients who are receiving cocktails of other HIV drugs. A final, worldwide trial will begin shortly, he said.

“This is a very potent new therapy with a tremendous amount of promise,” Hopkins said.

Trimeris also has begun clinical trials of another fusion inhibitor called T-1249. It is an artificial peptide that differs slightly from T-20. Its primary advantages are that it is effective against viruses that have been made resistant to T-20 in the laboratory and that it persists in the bloodstream much longer. Hopkins speculated that it eventually could be injected every other day, rather than twice a day as T-20 is.

T-1249 has passed safety trials, and efficacy trials are now underway in about 60 to 70 patients, he said.

On another front, Dr. Erik De Clercq of the Rega Institute in Leuven, Belgium, described studies with a molecule called AMD 3100, a member of a class of chemicals called bicyclams. AMD 3100 binds to the CXCR4 receptor on human cells, preventing HIV from binding and entering.

The drug has passed safety trials in 13 patients, De Clercq said, and the Rega team has just begun efficacy trials. Unfortunately, the drug must be administered intravenously or by injection.

Test tube experiments, Hopkins said, indicate that T-20 and AMD 3100 are even more powerful when used together.

Dr. Bahige Baroudy of the Schering-Plough Research Institute described a simple molecule called SCH-C that blocks the CCR5 receptor. The molecule can be given orally and has been found to be very effective in genetically engineered mice with a human immune system. The company hopes to begin human testing this year.

And last Friday, a Merck team reported in Science magazine that they had for the first time found two molecules that block the action of a viral enzyme called integrase. The two chemicals did not halt HIV infection in animals, they reported, but the compounds should point the way to others that will.