Key Clues Helped Pleconaril Scientists

- Share via

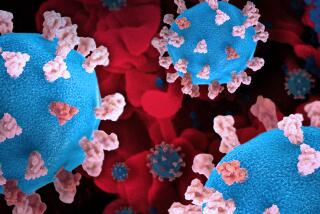

EXTON, Pa. — The viruses responsible for most colds and meningitis are icosahedrons. But that is just one of the things no one knew in the early 1980s when the search began for a cure.

Icosahedrons? For the non-geometry whizzes among you, that’s a 20-sided solid.

The quest for the drug that eventually became pleconaril started the old-fashioned way, with no clue to what rhinoviruses and enteroviruses looked like. Chemists at Sterling Winthrop Inc. tested thousands of off-the-shelf chemicals against the rhinovirus to see if any of them did anything.

One of them seemed to slow down a few of the 101 varieties of rhinovirus, but it was not very potent. The work inched along until a big breakthrough in 1985: Michael Rossmann of Purdue University led a team that mapped the three-dimensional structure of the cold virus.

Finally, Sterling scientists knew what their target looked like, and it quickly became apparent what their research drug was doing.

The 20 sides of rhinoviruses and enteroviruses are dented by a meandering crater. Inside the crater is the precise spot where the virus squirts its genes into the cells it infects so it can make new copies of itself.

The drug plugs up this crater, acting like a key broken off in a lock. Unable to pull away its outer coat and insert its genes, the bug is rendered harmless.

Eventually, the scientists learned that the outside of the virus has 60 spots where pleconaril can potentially lock on. At least five of these need to be filled to stop the virus from infecting.

*

Knowing how the drug should work, the scientists could begin what’s called rational drug design. They tinkered with the molecule every which way to make it fit perfectly into the slot. Since the cavern varies in size among viruses, the scientists settled on an average-size plug that would nicely fit them all.

They fiddled with the drug some more to make it resist quick breakdown in the bloodstream. Because no animals get colds, they decided to test it first on mice to see whether it would protect them from the polio virus, a form of enterovirus.

Ten mice got pleconaril. Ten did not. All the pleconaril mice remained healthy, while the rest were paralyzed and died. This was the first clear evidence that the drug actually stops these viruses in living things.

In 1994, the French drug firm Sanofi bought Sterling and stopped the research. Several Sterling employees formed ViroPharma Inc., bought U.S. and Canadian rights to pleconaril, and continued development.