Public Project’s Chief: Quiet but No Pushover

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Everybody has a particular way of entering a room. Francis Collins’ is to come in quietly behind controversial figures.

In 1992, Collins took charge of the publicly led Human Genome Project after James D. Watson, the voluble co-discoverer of DNA’s structure, quit in a spat with his government superiors.

He was pushed farther into the limelight when J. Craig Venter, the mercurial president of Celera Genomics, announced his determination to beat Collins’ team to cracking the genetic code. Collins objected to Celera’s intention to stake a private ownership claim to some of the code and helped negotiate a detente with Venter.

And Monday, Collins followed President Clinton into the East Room of the White House to declare that the study of the genetic code is in good hands and already yielding new drugs and treatments.

“Francis Collins reassures people that everything is proceeding as it should,” said Rep. John E. Porter, the Illinois Republican who chairs the House Appropriations subcommittee that oversees the National Human Genome Research Institute, which Collins runs. “When he talks, it’s calm and solid.”

Potent Combination

Yet Collins is no pushover. In helping to bring peace to the genomic world, for example, he has given precious little ground in his goal of ensuring that the deciphered genome is freely available to scientists everywhere. He harbors great ambitions about what they should do with it.

“Francis has very big plans,” said Dr. Harold Varmus, the president of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York and Collins’ boss when he was director of the National Institutes of Health.

The unusual combination of accommodation and ambition, of deference and aggressiveness, comes up repeatedly in conversations with Collins’ colleagues and associates. As one listens to his careful explanation of the project’s mission, there is no escaping the sense of a consummate political player at work.

“He is a clever, very savvy guy who has no intention of losing at this game,” said Dr. Bernadine Healy, president of the American Red Cross who, as NIH director in the early 1990s, hired Collins.

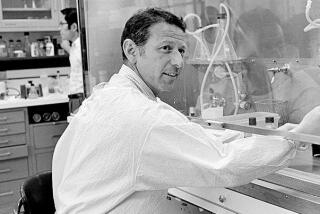

In appearance, Collins, 50, is a nerd’s nerd. He seems inseparable from an academic’s tweed coat; his collection of ties is one of the world’s worst. His daughter cuts his hair, often leaving him with a monk-like bowl cut.

But at 6 feet, 4 inches tall, he is also impossible to overlook.

This seeming straight arrow was brought up as a hippie on a farm near Staunton, Va., where his father taught drama at the local college and his mother was a playwright. He was home-schooled until the sixth grade, in part to be available to join the ragtag band of students, artists and intellectuals who passed through the house in pickup concerts and plays.

Allowed to attend the local high school, he graduated as class valedictorian at 16. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Virginia at 20, despite getting his girlfriend pregnant and starting a family at 19.

From there he earned a doctorate in theoretical chemistry at Yale University when he was 23 and a medical degree from the University of North Carolina at 27.

Back at Yale on a postdoctoral fellowship in the early 1980s, Collins devised the techniques that helped make his scientific reputation as one of the earliest and most successful human gene hunters. Over the decade, he and colleagues picked through the still-undeciphered genetic code to locate genes for a series of hereditary diseases, including cystic fibrosis.

It was also during this period that he honed some of his personal--and political--skills. Yale’s clerical staff was in a bitter struggle over unionization, and the genetics department’s secretary was deeply involved. “But for Francis,” said Collins’ mentor, professor Sherman Weissman, “he would come in and work all Saturday.”

Such skills proved valuable in Washington. Over the last seven years, Collins has orchestrated a threefold increase in the genome institute’s budget, established an internal research program that was viewed with suspicion by many university-based scientists and led the sometimes balky genome project through what many view as its greatest crisis, the unexpected challenge from Celera.

Scientist and Christian

Collins is also a rare combination of premier scientist and devout Christian. He professes belief in a God that is beyond the reach of science. He says the pursuit of the genetic code is not, as some worry, an attempt by humans to play God, but only humans’ way of admiring God’s handiwork.

“God is not threatened by all this,” he said in a recent television interview. “I think God thinks it’s wonderful that we puny creatures are going about the business of trying to understand how our instruction book works, because it’s a very elegant instruction book indeed.”

Collins’ success has not come without costs. His first marriage ended in divorce. (He has since remarried.) A student in his personal lab was accused of fabricating data, forcing Collins to withdraw five scientific papers. He and Venter got locked in a series of deeply personal clashes.

But now, Collins says, the fun can begin.

“This beats splitting the atom,” he said in a recent interview. “This beats going to the moon. This is an adventure with consequences.”