State Petition Carriers Getting Mixed Reception at Big Retailers

- Share via

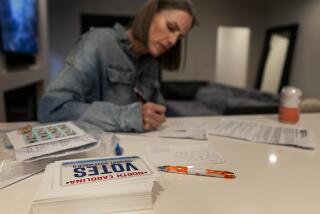

There are 21 statewide initiatives on your March 7 ballot, thanks to people like Christina Gioffre of Tustin who daily stake out storefronts of Costco, Home Depot and other retail stores, canvassing shoppers to sign petitions.

Last week, the 31-year-old Gioffre was working toward the November ballot. As shoppers exited Trader Joe’s in Irvine, she asked them to help qualify three initiatives that would approve school vouchers, outlaw “hidden” taxes and give judges the freedom to divert nonviolent drug offenders to rehabilitation programs.

These days, Gioffre, who works for Progressive Campaigns, a professional petitioning firm in Santa Monica, keeps one eye on shoppers exiting the store and another on the lookout for a store manager who may ask her to leave the premises. Retailers like Trader Joe’s are restricting--or outright banning--signature-gatherers from working in front of their stores.

The petitioners, who have countered with a slew of lawsuits, say their activities are protected by a landmark 1979 California Supreme Court decision guaranteeing the right of petitioners to collect signatures in privately owned shopping centers.

But some retailers, including Costco, Wal-Mart and large grocery chains, say they are not bound by that decision because many of their properties are free-standing stores--not connected to larger shopping centers.

The suits, now winding their way through courts from San Diego to Sacramento, have enormous significance for Californians, who have a long-standing tradition of using their right to petition to pass laws, recall elected leaders and vote on referendums.

The lawsuits also raise important legal questions about the role big retailers play in contemporary American society. Have they become the modern-day town squares where 1st Amendment rights can be exercised? Or are they private properties that are off limits to such activities?

A running feud between Raley’s supermarket in West Sacramento and signature-gatherers affiliated with Progressive Campaigns epitomizes the disputes--pitting free speech versus property rights--that have erupted across California.

In 1996, Raley’s employees placed under citizen’s arrest six petitioners who were gathering signatures in front of the store without management’s permission. (During the last two years, about 200 signature gatherers have been placed under citizens arrest for similar activities, by some estimates.)

The Yolo County district attorney’s office refused to file charges against the petitioners, who sued Raley’s for wrongful arrest and emotional distress.

Last year, Superior Court Judge Thomas E. Warriner dismissed the petitioners’ claims.

“By architectural design and marketing strategy, Raley’s is not a place of congregation nor a substitute town square or municipality,” Warriner wrote, emphasizing that Raley’s was not a “public forum” as defined in the so-called Pruneyard case by the California Supreme Court.

That case held that free speech guarantees in the state Constitution allowed a group of students in San Jose to set up a card table and collect signatures at the Pruneyard Shopping Center. The justices, who compared shopping centers to town squares, excluded from its holding proprietors of a modest retail establishment and said property owners could adopt reasonable “time, place and manner rules” regulating petitioning.

A few weeks ago, attorneys for the petitioners appealed Warriner’s ruling to a state appeals panel in Sacramento. If Warriner’s decision is upheld, Sacramento attorney Mark Merin argued, other retailers will “follow suit and the most popular . . . sites at which to gather signatures on petitions to place initiatives on the statewide ballot would be closed to free speech.”

Retailers like Raley’s, Costco and Wal-Mart are favorite spots of petitioners because, unlike at shopping malls, shoppers could easily be solicited near the limited number of exits of these stores.

And since shoppers visit these stores a few times each month, petitioners, who earn between 50 cents and $2 per signature, can collect signatures for a few weeks at each location before the pool of potential signers is exhausted.

Dale Gronemeier, a Pasadena attorney who represents petitioners in so-called solicitation cases across the state, said the surge in such cases represents a move by retailers to overturn Pruneyard.

“If you’re going to have a vigorous grass-roots democracy, you have to be able to gather signatures,” Gronemeier said. “These rights go where the people go and right now they’re going to large supermarkets and retail stores.”

“Tell me, what possible business interference can be caused by a couple of orderly petitioners collecting signatures in front of a retail store?” Gronemeier asked.

But many retailers disagree. They say they have adopted rules regulating petitioning because signature gatherers have gotten more aggressive.

Costco, for example, now bans petitioning at its stand-alone stores and prohibits petition pushers from collecting signatures in front of its other stores during 34 “peak traffic days” of the year. The discounter’s tough new rules have triggered about a dozen lawsuits.

David F. McDowell, a partner with Morrison & Foerster in Los Angeles, which represents Costco, said his clients adopted the new rules to protect its corporate image.

“If customers have bad experiences because of a hostile petitioner, they leave with a negative impression of the company.” McDowell said.

But Angelo Paparella, owner of Progressive Campaigns, disagreed. “It just doesn’t make sense,” he said. “If petitioners are rude or hostile, they will get less signatures.”

Gioffre, for example, smiled and greeted each customer as they exited the Trader Joe’s in Irvine. One shopper, Dolores Ostlund, volunteered to sign the petition that would offer rehabilitation to drug offenders, pointing out that such a program would have helped a drug-addicted relative if it were available. “I won’t be able to say how I feel if these petitioners weren’t in front of the store,” she said. “How else would we know what’s going on. I don’t read the newspaper.”

Experts agree that the California Supreme Court may eventually have to revisit the issue to determine if big retailers should be treated as shopping centers.

In the meantime, restricting access to these storefronts could mean that getting the 700,000 signatures needed to qualify a petition for the ballot could get more expensive, according to Robert Stern, co-director of the Center for Governmental Studies, a nonprofit research group in Los Angeles.

“Instead of someone coming up with the $1 million it now takes to qualify a petition for the ballot, they’re going to have to come up with $10 million,” Stern said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.