Strike Threatens to Paralyze Two Seattle Newspapers

- Share via

SEATTLE — Both of Seattle’s major daily newspapers were locked in a strike Tuesday that threatened to paralyze news operations, production and delivery at the opening of the crucial holiday advertising season.

“I’ve got a very empty newsroom full of managers right now,” Ken Bunting, editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, said Tuesday morning. “I’m going to have to see if I remember how to write.”

Hundreds of editorial, advertising and circulation workers at the Post-Intelligencer and the Seattle Times walked out at 12:01 a.m. after a federal mediator failed to bridge a bitter wage dispute and left both sides facing the prospect of a strike that could go on for weeks.

The two papers, locked for years in an escalating cross-town readership war, faced the unusual prospect of a joint strike because of a joint operating agreement that covers business operations and production, but not editorial content.

Newsroom managers brought in outside help and struggled to put out papers in one of the heaviest news weeks of the decade--including a down-to-the-wire U.S. Senate race here that is being watched nationwide. The strikers immediately opened their own newspaper on the Internet, with reporters and photographers who normally compete working side by side on what might become the city’s best source of news content.

But Mason Sizemore, president and chief operating officer of the Seattle Times, said management was “prepared to print and distribute both the Seattle Times and the P-I. We will do that today, without the people who chose not to come to work, and we will produce credible newspapers.”

“The surprising thing to me is the number of Newspaper Guild employees who have crossed the line and are working at their normal jobs,” Sizemore said.

It was clear the strike will significantly affect operations at both newspapers, however. Teamsters drivers, who transport newspapers from the printing plant to distribution warehouses, have served notice that they plan to abandon their trucks and join the picket lines. Press operators were considering joining them.

The Pacific Northwest Newspaper Guild includes editorial workers, as well as most operational employees, from composing room workers to classified advertising salespeople and the clerical staff. Most of the phones at both newspapers had no operators to answer calls; readers who sought to cancel their subscriptions in support of the strike could not get past an automated greeting.

Washington’s Democratic governor, Gary Locke, and King County’s Democratic county executive, Ron Sims, both said they would not grant interviews to reporters who crossed picket lines at the two newspapers.

P-I management said it would publish a much-reduced, 24-page version of the newspaper today, written by non-Guild editors and employees brought in from other publications of the Hearst Corp., owner of the P-I. The Seattle Times is owned by a Frank Blethen family enterprise in which Knight-Ridder holds a 49.5% share.

The newspapers are both aided and hampered by the joint operating agreement, under which the Times handles all production and advertising while the P-I produces its own editorial package and shares in 40% of the profits.

While readers have no option to switch to a newspaper not crippled by the strike, the complexity of ownership and newspaper cultures makes settlement a more difficult prospect, said Vandra Huber, associate professor of management and organization at the University of Washington.

“When you’re talking about the negotiations, there are multiple parties involved, so that increases the difficulty in reaching a resolution,” she said. “With the union, you’ve got one Guild but two different papers. And each of those cultures is slightly different. And then within the two newspapers, you have the same sort of multi-commitment.”

Although the Puget Sound economy has been one of the fastest-growing in the country, Guild members say recent contracts have fallen far short of the rising cost of living--setting up a situation in which employees feel compelled to dig in for a better deal.

Management’s final offer was for an overall raise of $3.30 an hour over a six-year period. The Guild had sought a three-year contract with an overall raise of $6.15 an hour, then lowered its demand to $3.25 an hour, still over three years. There also are disputes over a two-tiered wage system, in which suburban reporters earn less than their downtown counterparts (the company has offered to phase that out over a six-year period), and over retirement and sick leave benefits.

Currently, the average minimum wage for a reporter with six years’ experience is $844.88 a week, or $21.12 an hour.

“The offer on the table was as good as or better than recent Newspaper Guild contracts around the country, including San Jose and Detroit. I don’t understand what the issues are, if that kind of offer is deemed to be insulting, as the Guild describes it,” Sizemore said.

Larry Hatfield, a reporter from San Francisco and an administrative officer for the Guild, said the offer was far from adequate.

“A lot of people think the strike is about money, but it’s not, really. It’s about respect,” Hatfield said. “The workers at the Times and the P-I for many years have accepted bad contracts, and as a result we have a situation where the cost of living in the Puget Sound area has increased since 1989 by 43.9%, whereas the wages at the Times and P-I have increased well under 30%.”

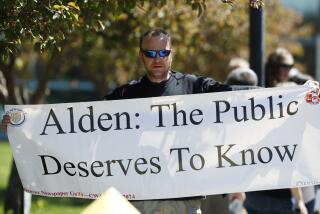

On the picket lines, employees said they were determined to make a statement, even if it meant a holiday season without a job. Strike pay, through the Communication Workers of America, is $200 a week.

“My feeling is if you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything. They don’t have to struggle every day like we do,” said Regina McRay, a classified advertising saleswoman.

“I worked 23 years trying to help the Seattle Times be a great newspaper, but it wasn’t a difficult call for me. If the union goes on strike, I go on strike,” said longtime feature writer Jack Broom, who was acting as a morning assignment editor at the online strike paper, www.unionrecord.com.

Guild members said they expect to begin producing a print version of the online paper within a week. The Times and the P-I, meanwhile, told subscribers that their papers would be free until the product is brought back up to par. Faced with the prospect of a holiday advertising season without means to produce full papers, both newspapers published their day-after-Thanksgiving advertising supplements Monday.

“There really is an obligation we have to our readers and our advertisers,” P-I Publisher Roger Oglesby said. “But it’s difficult. This is not a situation that anyone is enjoying. People are working hard down in the newsroom just to get this paper out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.