How One Texan Got a License, Then Killed 2

- Share via

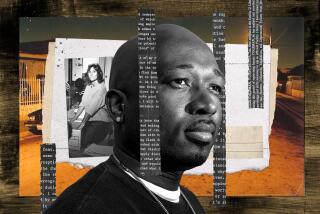

LIVINGSTON, Texas — Robert Clinton Hinkle lived life hard--the bandit biker gangs, the death threats, the drugs, the gunfights too many to count.

But then something odd came real easy--his plastic concealed handgun license card from the state of Texas.

He mailed in the yellow, 19-question application, passed a written exam and a shooting test, and soon became one of the tens of thousands legally walking around Texas with a hidden firearm.

With his new license slipped neatly in his wallet, he carried a .380 semiautomatic in a shoulder holster and a .41-caliber magnum Smith & Wesson tucked under his belt at the back of his pants.

Hinkle was armed. He was also dangerous.

In fact, he is among the most egregious examples of how the state of Texas has granted hundreds of concealed-weapon permits to citizens with questionable backgrounds. Roughly a year after he received his license, Hinkle killed two men and seriously wounded a third in a wild shootout over drugs.

Hinkle is in prison in Livingston, probably locked up for the rest of his life, but he laughs when he talks about how little effort it took to get the concealed handgun license. “It just fell into my hands,” he says, sitting in the maximum security penitentiary next to Texas’ death row.

Law enforcement officials in Texas maintain that because Hinkle had no prior criminal history, there was no reason for him to be denied a license.

Ray Nutt, chief investigator in the district attorney’s office in Henderson County, Texas, where Hinkle was tried, convicted and sentenced, called it unfair to blame the state program for awarding Hinkle a license in 1996.

“You’re always going to have a few people who slip through,” Nutt said. “And if you wrote the law so Hinkle couldn’t have one, then nobody could have one.”

Even local prosecutor Shari Jenkins Moore, who helped put Hinkle away for so long that he won’t even be eligible for parole until he is nearly 90, said that while in hindsight he should not have gotten a license, the program is sound and should not be changed.

“Given his history, I don’t think anybody made an error giving him one,” she said. “A lot of it is whether you’re honest about who you are and why you want the license.

“Because even if you beat up your wife and shove a gun in her face, if you’re not convicted of that, you’re going to slip through.”

But Herman Porter, a federal agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, has a different perspective because he had earlier investigated Hinkle and his world of violent biker gangs. Asked whether Texas should have licensed Hinkle to carry a concealed weapon, Porter replied:

“Are you kidding me?”

A Love Affair With Motorcycles

A Texas native, Hinkle loves guns (he kept as many as seven around his home at any one time) and he had long been a hunter.

But motorcycles, Harley Davidsons mostly, were his real love. Even though he was nicknamed “Pokey,” he bragged in the prison interview that he once built the fastest Harley around, one that could fly at 187 miles an hour.

Twenty years ago he began riding with the Banshees, a biker gang, and soon was flaunting the trappings of that nether world--heavy beard, ponytail, black leather boots, blue dragon tattoo on his left forearm.

“It was like a family,” he said. “We would drive to the lake and drink a few beers, maybe 40 or 50 of us.”

Hinkle was an expert motorcycle mechanic, brought into the “family” because he could build fast bikes.

In the early 1980s, things turned ugly. The Banshees were challenged by another biker gang, the Banditos. According to Hinkle, the Banditos did not want the Banshees wearing the words “Texas Rocks” on the back of their riding jackets. There soon was an altercation--shots fired, knives flashed and one Bandito was left dead.

Porter, the ATF agent, helped put a prosecution together, in which he said about 20 Banditos were convicted of various crimes.

Hinkle was called as a government witness to demonstrate to the jury what kind of person joins an outlaw gang. “He was pretty raunchy looking,” Porter said. “We tried to clean him up a bit in court, but he was still just a dirt bag biker.”

Hinkle said his life went into a tailspin after his court appearance. He said that a bounty was placed on his head for testifying against the Banditos--and that the reward was a five-gallon jug of P2P, an oil base that is a critical ingredient used in methamphetamine.

What followed, he said, was a series of attempts on his life. Suspicious characters began showing up around his motorcycle shop near Dallas and someone placed a bomb on the gas meter at his home, destroying a side of the house, he said.

So Hinkle moved east to Eustace, Texas, to elude his enemies, he said. But he kept his shaggy look (ponytail down his back and the beard down to his chest). He kept tinkering with motorcycle engines, did drugs daily, and always, he said, worried about his safety.

And then another friend told him about Gov. George W. Bush’s concealed weapon program. “It was well-known in Texas,” Hinkle said.

Hinkle requested an application, and when the form arrived he said he hastily filled it out, not mentioning (because he was not specifically asked) the biker gangs, the drugs, or the gunfights. He wrote out a check for $140 and sent it on to a state Department of Public Safety post office box in Austin, along with two sets of fingerprints, one for state officials, the other for federal law enforcement.

The fingerprints were how officials would check a person’s background. Hinkle’s background came back clean. So next he was invited to show up at the Blue Mallard rifle range and gun shop in Athens, Texas, to take a two-day fitness course.

Seven prospective licensees showed up. They were asked questions about gun safety, such things as whether you could shoot a man if he was driving away in a van with furniture stolen from your home.

“Did I have the right to kill him? I said no,” Hinkle said.

Hinkle Carried Guns Everywhere

He said other questions dealt with whether you could shoot a man who was hitting you in the stomach or kicking you in the back. Hinkle answered no. “Only a blow to the head gives you the right to pull a weapon,” Hinkle said.

Hinkle answered the questions correctly, and he and the other students passed. The next day they returned to the range for shooting proficiency. Hinkle brought his handguns and shot well, notching 242 points out of a possible 250.

Three months later, his license card arrived by mail and he began carrying his guns everywhere. Once he was stopped by a cop while using a phone booth in nearby Gun Barrel City, Texas. He simply opened his wallet and flashed his concealed gun license, and that was the end of that.

Finally, four days before Christmas 1997, in the living room of his trailer home on old Country Road 2813, Hinkle shot and killed Henry Adams and Gary Junell. A third man, James Ashton, was shot three times in the back and stomach. He lived to testify against Hinkle.

The authorities said Hinkle just suddenly snapped, grabbing his Smith & Wesson and firing away. They said the argument was over that jug of P2P (known as Phenyl-2-propanone), worth about $370,000.

Hinkle said it was self-defense, that one of the men hit him over the head with the butt of a shotgun and that Hinkle shot the trio to save himself. In the interview, Hinkle broke down at one point, saying through his tears: “They were supposed to be my friends.”

When the case was tried early last year, prosecutors decided to seek a life sentence rather than the death penalty. Hinkle was already 46, and under a life term he would have to do 40 years before he could see a parole board.

At one point during the trial, Hinkle did testify about how he had gotten his concealed weapon license. “You have to qualify in the eyes of a law, federal law,” he said, confusing the legal jurisdictions. “And, basically,” he added nonchalantly, “that’s about it.”

The jury said guilty after deliberating only five hours and the judge said life.

Moore, the prosecutor who helped put him in prison, said Hinkle is a perfect example of the Texas male and his love of guns.

“Tomorrow, my husband is going dove hunting. He doesn’t care a bit about shooting a dove. He just wants to shoot his gun.

“I guess that’s just the way Texas boys are raised,” she said.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Lifting the Veil

Secrecy provisions of Texas law creating the state’s concealed handgun licensing system prevent close public scrutiny of permit revocation cases, even those involving license holders who commit violent crimes and felonies. A Times request for names of Texans with revoked permits was rejected by state police and the state attorney generals office, citing confidentiality rules in that law signed by Gov. George W. Bush in 1995.

However, a computer-assisted team of reporters and researchers was able to identify for the first time many of the most serious law violators among the anonymous ranks of Texas handgun license holders.

The Times started with records of the Texas Department of Public Safety tracking actions to revoke licenses. The unnamed permit holders were identified only by their birth dates, gender, race and zip codes.

One was the case of a white male born April 12, 1952. His license was suspended July 3, 1998, after he was charged with a 1997 murder. His east Texas residence was in the 75124 zip code.

National and statewide computer databases were checked for everyone listed in the 75124 zip code to find everyone born April 12, 1952. In this case, only one name matched.

Next, crime record databases were run to see if any of those named had been charged with similar crimes and, finally, trial documents and court records were gathered from courthouses and police stations across Texas.

The license holder born on “4/12/52” turned out to be Robert Clinton Hinkle, 48, then living on Old Park Harbor Rd. in Eustace, Texas. He currently resides in a Texas state prison serving a life sentence for murder.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.