Microchip Co-Inventor Helped Start Revolution

- Share via

“I don’t know why nobody had seen it before,” Jack Kilby said Tuesday of the flash of insight he experienced in 1958, a few weeks after starting work at Texas Instruments.

His insight--that electrical components such as transistors, resistors and capacitors could all be manufactured out of the same material, silicon, and could therefore be etched on a single chip of the material--helped launch a trillion-dollar industry and revolutionized daily life around the world.

On Tuesday it also won Kilby the Nobel Prize in physics.

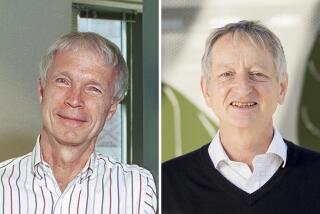

The 76-year-old Kilby, a plain-spoken Kansan who had already won almost every other accolade the engineering profession has to give, called the award “not one I expected at all. The prize goes to people who come up with some exciting new physics,” he said in an interview from his Dallas home. “The integrated circuit didn’t have much new physics in it.”

What it did have was inspiration.

As legend has it, Kilby was working in a deserted lab at Texas Instruments’ Dallas headquarters in July 1958, so new an employee that he was not eligible for the two-week vacation being enjoyed by the rest of the staff. The problem before him was known as “the tyranny of numbers”:

The invention of the transistor in 1947 had allowed engineers to design increasingly complex circuits with hundreds of electronic components. But the need to hand-solder them all together raised costs, created production bottlenecks and introduced countless potential failure points.

Various schemes of automating circuit assembly had been proposed “but I wasn’t enthused” about any of them, Kilby recalled. “I thought it more desirable to form the components all out of the same material.”

Once he recognized that not only transistors but the other components could be made from silicon, “they could also be made in situ, interconnected to make a complete circuit.” The circuit might lose some efficiency because capacitors and resistors were better made from other materials--but it would gain more by eliminating the need for separate interconnections.

By Sept. 12, 1958, he had produced a working circuit on a half-inch sliver of germanium, which like silicon is a semiconductor: a material that both conducts and moderates the flow of electricity.

Kilby’s invention, as refined, patented, and marketed by TI early the following year, did not win instant acceptance from the business world. For one thing, many doubted that the tiny chips could be manufactured economically. That changed with a refinement of the circuit design by Robert Noyce, a founder of Fairchild Semiconductor and later of Intel Corp.

As it happens, TI and Fairchild battled in court for years over their rival patents, eventually reaching a settlement in 1969 that resulted in both Kilby and Noyce sharing credit for the invention of the integrated circuit. Noyce died in 1990.

In time the microchip took over the world of electronics. As the trend of miniaturization proceeded, the chip that Kilby fashioned with a single transistor begat today’s versions, which can comprise 20 million transistors or more in the same space. The bottleneck of complexity shattered, microchips today perform with limitless potential as the brains of devices as diverse as desktop computers, automobiles and hearing aids.

Kilby acknowledged that his invention has had “many beneficial effects. I got a great deal of recognition, and I get a great deal of satisfaction watching [the technology] progress.”