Overlooked Ancient Wonders: Fish Weirs

- Share via

The Aztecs, Incas and Mayas have long been recognized for the architectural skills that produced impressive cities, temples and pyramids of stone.

Residents of the Amazon lowlands, in contrast, left behind no massive monuments. As a result, researchers once assumed that those people never achieved the high level of social organization necessary for such public works projects. It is widely thought that they survived as relatively isolated hunters, gatherers and subsistence farmers.

But research over the last three decades has begun to paint a substantially different picture of people such as the Baures of the Bolivian Amazon. It has now become clear that they, too, were capable of massive construction projects requiring the sophisticated organization of large groups of people.

What they built didn’t last, however, because they used mud, not stone.

Moving millions of tons of earth, the Baures constructed raised platforms for towns and cities and dug moats around them. They also built massive causeways between villages, elevated fields for intensive farming, canals and reservoirs.

Now a new study suggests that they also created levees and embankments that trapped water during seasonal flooding of the lowlands. This enabled them to increase their water supply and trap and hold large quantities of fish.

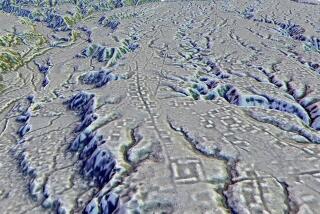

This previously unnoticed network of fish weirs spreads over 326 square miles of the flat savanna of the Baures region of Bolivia near the Brazilian border, according to archeologist Craig Erickson of the University of Pennsylvania.

Taken together, the evidence indicates that the Baures were able to modify landscape in complex ways to support their lifestyle.

“Rather than domesticate the species that they exploited, they domesticated the landscape,” Erickson said.

Erickson’s work has overturned “the conventional view that seasonally flooded savannas are worthless for cultivation and suitable only for cattle ranching,” according to archeologist Warwick Bray, who is retired from University College in London.

Unfortunately, the earthworks were largely abandoned 300 years ago at about the time of the Spanish conquest. The population was decimated by measles, smallpox and other diseases brought to the New World by the Spanish. The survivors moved away.

Today, a region that once supported a dense population by intensive agriculture is largely deserted, the land fit only for cattle grazing. “It was a large garden, manicured and taken care of for thousands of years,” Erickson said. And now the man-made improvements are barely recognizable.

Erickson first noted the unusual pattern of earthworks while flying over the region, observing unusual zigzag structures from the air. Closer examination revealed a dense network of interconnected levees about three to seven feet wide and seven to 20 inches tall.

The weirs change direction every 30 to 100 feet, and at each intersection is a funnel-like opening three to six feet long and wide.

The savanna floods with a thin sheet of water during the rainy season, which lasts from December to May. During this period, fish enter the savanna from the rivers, lakes and wetlands, only to return to their original habitat when the land dries up.

But when the weirs were intact, their zigzag shape would hold back the water, slowing its return to the rivers and trapping the fish. The weirs’ builders were able to hold baskets at the openings to catch fish that were funneled through them as the water receded.

The weirs are similar to ones used by native peoples in South America today, but with a major exception. Fish weirs today are generally constructed in permanent bodies of water and rebuilt every season. The old weirs were earthworks built in a body of water that came and went.

The earthen weirs were planted with royal palm trees, which were a valuable source of raw materials. Fronds from the trees could be used for thatching roofs, trunks for house beams, wood for bows, and heart of palm and palm fruits for food. Fruit from the trees attracted game animals that could be killed for food.

The Baures dug circular ponds about 90 feet in diameter at more or less regular intervals along the weirs. The ponds served to store both water and fish for consumption during the dry periods. Many of the ponds are still well-stocked, Erickson said. “While we were working there, we ate fish from them nearly every night,” he added.

The weirs no longer carry out their function because they have been partially destroyed by scavengers. The soil they are composed of contains lots of potsherds and other materials, Erickson said, and has been widely mined to fill roads.

Erickson hopes to restore a segment of the weirs, perhaps covering an area of one to two square miles. “We would watch it for the course of a year and see what happens to the fish,” he said. “It could potentially increase the natural carrying capacity of the land.”

But it is unlikely the entire system can be restored, he added. The people who would most benefit from the weirs no longer own the land. Instead, it is owned by rich farmers who are content to graze cattle.

*

Maugh can be reached at thomas.maugh@latimes.com