Slayer of Game Wardens Is Denied Parole

- Share via

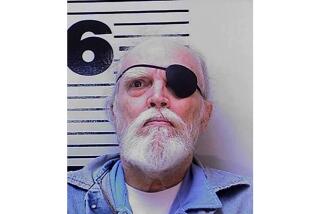

BOISE, Idaho — An unrepentant, defiant Claude Dallas was denied parole Thursday for the 1981 slayings of Idaho game wardens Bill Pogue and Conley Elms.

Dallas, who addressed the Idaho Commission of Pardons and Parole by telephone from a Kansas prison, expressed no remorse. He scorned such restrictions as drug testing or electronic monitoring as a condition of early release.

He said he would rather serve another four years behind bars than be freed under close supervision.

“By God, I will not submit. I’ve set my mind on this,” Dallas said. “I see more threat from the damn government than from all the drug lords on the face of the Earth.”

After hearing from Pogue’s son, an Idaho Department of Fish and Game officer, and a friend of Elms’ widow, the five-member commission said Dallas should remain imprisoned until his 30-year sentence--minus administrative reductions--ends on Feb. 6, 2005. He could have been eligible for parole on Sept. 22.

He is serving his time in Kansas’ El Dorado Correctional Facility, about 25 miles northeast of Wichita.

Friends and relatives of the victims said they were pleased by the commission’s ruling, but subdued by the thought that the saga would resume when Dallas is released in less than four years. The case of the 50-year-old Ohio native and gun enthusiast was the subject of two books and a made-for-television movie.

“We are certain he will never feel the need to follow our nation’s rules and regulations and will kill anyone who gets in his way,” Steve Pogue, Bill Pogue’s son, told the commission. “We believe it won’t take long before he does what he has to do again in order to live the lifestyle he believes he’s entitled to.”

After being informed of the commission’s decision, Dallas said simply: “All right.”

The former ranch hand and trapper shot Pogue and Elms to death on Jan. 5, 1981, at a remote high-desert camp in extreme southwestern Idaho rather than be taken in for poaching. He has maintained he acted in self-defense, despite an additional shot to the head of each victim after they already had been gunned down and efforts to hide or destroy the bodies and other evidence.

A jury acquitted Dallas of first-degree murder but convicted him of voluntary manslaughter, concealing evidence and using a firearm.

He eluded capture for 16 months after the slayings, then escaped from an Idaho prison during Easter weekend of 1986 and was on the run for 11 months before being recaptured in Southern California.

Olivia Craven, the parole board’s executive director, said correspondence received this year on the case from throughout the country was the most she had seen on any inmate in 17 years. Only a handful of letters supported parole. Opposition to his release filled the rest of three large three-ring binders.

During the hearing, commissioners asked Dallas why anyone should believe he would not pose a threat to law officers if released early, a fear voiced by many of the estimated 2,000 people who wrote or e-mailed the panel.

“I don’t see that as being a problem,” he replied. “As long as I’m approached in a reasonable manner, I respond in a reasonable fashion.”

Dallas refused to say whether he felt any remorse about the slayings.

“My thoughts and my feelings are my own,” he said. “They don’t belong to the state of Idaho.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.