Tentative Pact OKd to End Strike at Seattle Newspapers

- Share via

SEATTLE — Six weeks into a walkout that hobbled both of Seattle’s daily newspapers, negotiators on Thursday reached a tentative settlement that would bring all the strikers back to work within six months.

But the proposed contract, which could be voted on as early as this weekend, provided few additional financial concessions to workers--and left both the Seattle Times and the Post-Intelligencer with millions of dollars in advertising and circulation losses.

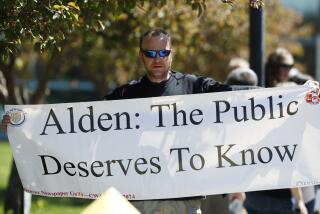

The often-bitter, 46-day action by the Pacific Northwest Newspaper Guild, during which management successfully delivered papers to all subscribers, failed to attract crucial support from other unions. It also left the two newsrooms with rancorous divisions that guild members said could take months--or years--to heal.

Analysts said the strike provided further evidence of the difficulty of mounting successful job actions against an industry that is increasingly computerized and able to produce papers without skilled typesetters and other production workers.

The last major U.S. newspaper strike--against the Detroit News and Detroit Free Press--lasted five years and cost both papers $200 million. That action resulted in the replacement of all striking workers and a reduction in total staffs by several hundred.

Seattle guild leaders said they won important concessions in health care benefits and pay scales for suburban reporters, in addition to an overall wage increase of $3.30 an hour over six years.

More than that, they said, they forced the management of the two newspapers--which publish under a joint operating agreement--to seriously negotiate labor contracts.

“In the past, they’d come to the table every time and flatly refuse to bargain wages and benefits. They put the number on the table, and you take it or leave it. This is the first time one of their unions has stood up and said that practice is wrong,” said Seattle Times sports columnist Ron C. Judd, spokesman for the guild.

“No, we didn’t gain a lot of money by going on strike. But in the future, we’ve really strengthened our ability to fend off take-backs in other areas. We feel like we’ve established ourselves as a legitimate bargaining entity in this newspaper,” Judd said.

For its part, the Seattle Times said the strike jeopardized one of the few family-owned newspaper chains in the country.

The Frank Blethen family “has a great deal of resolve and a very deep . . . commitment to stewardship of the Seattle Times,” said Kerry Coughlin, a Times spokeswoman. However, she added, something like the strike might have put the company in a precarious enough position that the family would have considered selling.

(Shortly before the strike, the Blethen family rejected a buyout offer from the Knight Ridder chain, which owns 49.5% of the common stock.)

Coughlin said the strike will force the Times to postpone expansion of its opinion pages and investigative staff, in addition to delaying the purchase of an additional press.

Total downsizing will amount to about 10% across the company, to be achieved through negotiated delays in bringing back striking workers, early retirement and expanded severance programs.

The timing and nature of the workers’ return was a key factor in prolonging the strike at the Times. Post-Intelligencer employees went back to work Tuesday. Under the joint operating agreement, Seattle’s two dailies maintain separate, competitive newsrooms, but the Times handles advertising, printing and distribution.

An all-night bargaining session Wednesday in the Washington, D.C., offices of Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and presided over by C. Richard Barnes, director of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service, produced the breakthrough on the return-to-work issue.

The Times agreed to shoulder a higher share of employees’ health care costs and to remove all replacement workers from guild jobs. The paper also pledged that all strikers would be brought back to their jobs within 180 days. Under the agreement, half must be back at work within 90 days.

Management at the Post-Intelligencer, which is owned by Hearst Corp., said it had not announced any layoffs, but it had suffered substantially from the strike.

“We don’t know exactly yet what the impact of the strike is going to be,” said John Joly, public affairs director. “But we are already talking about watching our expenses like hawks.”

Tuesday’s return to work, during which many Post-Intelligencer guild members wore ribbons in support of colleagues still on strike at the Times, was “really upbeat . . . there were lots of hugs all around,” Joly said. Publisher Roger Oglesby addressed the staff, Joly said, “and his remarks were focused primarily on getting back to producing a newspaper that’s outstanding in every way.”

The guild bargaining committee was scheduled to make a recommendation on the proposed settlement today, after which the membership would vote over the weekend.

Computerization Aids Management

Overall, industry analysts said, the strike illustrated the growing difficulty of using labor actions as a bargaining chip against newspapers, where increasing automation and computerization have left management able to operate without striking employees.

“This demonstrates once again that, in this era of newspapers being able to continue publishing despite a strike, that it’s almost always foolish for a union to go on strike,” said newspaper analyst John Morton of Morton Research Inc. in Silver Spring, Md.

“They are accepting essentially the same money terms that they walked out on, which means they’ve lost the difference between whatever strike pay they got and what their pay would have been had they stayed.”

But several guild members said management’s agreement to pick up a higher share of escalating health care costs was a substantial improvement, as was the agreement to phase out the reduced pay rate for suburban reporters within three years.

“I know this sounds cliche, but it was a thing about respect--and getting the company to respect the work I do,” said Keiko Morris, a Times reporter.

“I know [the contract] will be a hard thing to swallow for some people, but I think that people are going to recognize the long-term benefits of this,” she said. “We actually stood up for something. And the way the company deals with this union is going to change. It already has changed.”

Mark Trahant, the Times’ featured columnist on the West who left the paper during the strike to become head of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education in Oakland, said he did not agree with the strike but could not bring himself to cross picket lines. The strike’s true cost now, he said, will be measured in how many readers are lured back.

“A newspaper strike is still possible, but the rules have changed,” Trahant said. “My greatest fear is that people quit reading. I’m afraid a lot of people will just toss it and say, look, I got along fine for 45 days, so why do I need to subscribe again?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.