Is This Man Guilty of Crimes Against Humanity?

- Share via

Henry Kissinger is not a nice man. Funny sometimes, clever always, but not nice. Christopher Hitchens, as is his wont, makes the point a little more strongly: He wants Kissinger tried for crimes against humanity. He argues that many of Kissinger’s “partners in crime” have been punished, and he is angered by Kissinger’s ability to avoid prosecution.

As national security adviser and secretary of state to Richard Nixon and secretary of state in the administration of Gerald Ford, Kissinger was complicit in every major foreign-policy decision made in Washington from 1969 through 1977. Some of those decisions seemed appalling at the time; others are even more disturbing as documentary evidence is declassified a quarter of a century later (see, for example, Larry Berman’s forthcoming “No Peace, No Honor: Nixon, Kissinger, and Betrayal in Vietnam” to be published by The Free Press). Kissinger has succeeded in denying access to his official papers, and the full story of his activities is not likely to be known for at least 50 years, when the Library of Congress will open the Kissinger collection to researchers. Much of what the world knows about Kissinger’s actions comes from his own often informative, always self-serving, memoirs.

Hitchens, in “The Trial of Henry Kissinger,” declares himself concerned with only those Kissinger offenses open to legal prosecution. Mere “callous indifference to human life and human rights,” however depraved, is not his focus. He indicts Kissinger for prolonging the war in Vietnam by helping the Nixon campaign subvert the peace process in 1968 and for planning the attacks on neutral Laos and Cambodia. Looking back to the trials of Japanese war criminals in 1946, he finds Kissinger’s responsibility for war crimes greater than the culpability of at least one of the Japanese who was executed.

The most persuasive case against Kissinger relates to the overthrow of the democratically elected Chilean government of Salvador Allende in 1973. Someone in the Nixon administration should be prosecuted for ordering the kidnapping of Gen. Rene Schneider, chief of the Chilean general staff, a man who insisted the military should stay out of politics. Evidence that the CIA facilitated Schneider’s murder, which preceded the coup against Allende and the horrors of the Pinochet years, has been on the table for many years, and Hitchens does a lawyerly job of demonstrating Kissinger’s involvement.

Hitchens also reminds us of the unwillingness of Nixon and Kissinger to prevent or stop Pakistan’s brutal suppression of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1971. Its president, Yahya Khan, was serving as Washington’s conduit to Beijing, a service which to Kissinger outweighed his responsibility for massacring thousands of Bengalis. The United States would not jeopardize his assistance by criticizing him. Hitchens also spells out the American role in the Greek junta’s attempt in 1974 to assassinate Archbishop Makarios, president of Cyprus, and catches Kissinger and Ford acquiescing in the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in 1975.

Certainly the process by which Augusto Pinochet was recently detained in England at the request of a Spanish judge and the decision by the House of Lords that he was not protected from prosecution by sovereign immunity must be unsettling to Kissinger, as is evident in his account of these events in his new book, “Does America Need a Foreign Policy?” If, as Hitchens alleges, Kissinger committed crimes against humanity, he should be brought to trial. Simply that his transgressions were committed as an official of the most powerful state in the world should not exempt him from being held accountable for his actions. He is apparently safe as long as he remains in the United States, but can he be sure that a warrant will not be issued for his arrest during his next trip abroad? Do we want him to enjoy the human right of freedom from fear?

“Does America Need a Foreign Policy?” was not intended as a response to Hitchens, as a statement for the defense. The book nonetheless serves as an apologia for Kissinger’s past actions. Most of all, this is Kissinger’s testament, a discussion of the principles that should guide American policy. The book bears some resemblance to George Kennan’s classic “American Diplomacy.” Although it is more profound, it lacks Kennan’s elegant style. Surprisingly, Kissinger pays much more attention to economic issues than he did during his years in office.

Threaded throughout the volume is Kissinger’s contempt for the Wilsonian penchant for stressing American ideals rather than interests as a basis for policy. He assures his readers that the values of the American people are commendable and important but insists there must be a balance, that policy should be based on an “unapologetic concept of enlightened national interest.” He prefers Teddy Roosevelt’s big-stick approach to the world over that of Woodrow Wilson. Value-based policy leads to crusades, and Kissinger insists that ideological and religious struggles--which he appears to equate with demands for democratization and respect for human rights--cause more suffering than wars over the balance of power. He concedes that concern for human rights will influence American policy but argues that it should never affect decisions unless “there exists scope for discretion,” unless the policymaker can be certain that such scruples will not interfere with the achievement of his ends.

He is relentless in his criticism of the Clinton administration, those ‘60s types embarrassed by the exercise of American power. He is outraged by their apologies for actions he and others took in the course of the Cold War, disgusted by their excessive stress on democratization of the world and their insistence on finding unselfish causes. There was no strategic dialogue in Washington in the 1990s. A critical question for Kissinger is whether states have the right to intervene in the internal affairs of other states. The erstwhile professor offers a learned disquisition on the 17th century Westphalian international order, a system of peace dependent upon acceptance of national sovereignty and noninterference in the domestic conduct of other states. He is deeply troubled by the humanitarian military operations of the 1990s--Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo--and insists that the way states treat their own people is not a legitimate concern for other states, certainly not when it clouds geopolitical considerations. He does have qualms, however, when genocide is involved, as in Rwanda, and he would consider having the United States act to stop the killing.

In a section sure to delight Hitchens, Kissinger applies the Westphalian principle to situations, such as Pinochet’s crimes in Chile, in which efforts are made to transcend national boundaries to impose justice. In Kissinger’s mind, the case of Ex Parte Pinochet would be a terrible precedent that would not only violate traditional conceptions of sovereignty and the doctrine of nonintervention in domestic affairs but could also result in serious threats to Kissinger, as well as to China’s Li Peng and Uganda’s Idi Amin. At a minimum, he would have to think twice about foreign travel.

Scattered throughout the volume are artful excuses for some of the more troubling actions ordered by Nixon and Kissinger. When Kissinger criticizes the Kennedy and Johnson administrations for “missionary” efforts in Vietnam, for demanding democracy in the South while tolerating the sanctuaries and supply lines that the North established in Cambodia and Laos, he is attempting to justify the attacks Nixon ordered on those neutral countries. His discussion of the coup against Allende omits all mention of the murder of Schneider, and he insists Allende was a radical Marxist ideologue planning to impose a Castro-style dictatorship on Chile with Cuban help. He defends the coup by declaring that democratic parties in Chile welcomed it, although the outgoing president, a Christian Democrat, opposed interference. Pinochet may have few friends left in the world, but Kissinger is clearly one of them.

His discussion of suitable policies toward Asia will disgust anyone who remembers the policies he recommended while in office. There is no reference to his infamous tilt toward Pakistan in a moment of Indian-Pakistani tensions in 1971. Pakistan has disappeared from his concerns, and he insists upon the importance of India. Of course, in his day Indian leaders, poisoned by what they had learned at the London School of Economics, protected somehow by American liberals, talked all sorts of anti-American prattle and could not be taken seriously. Japan, Kissinger reminds us, is America’s most important ally in Asia, and there is some danger, he maintains, of its drifting out of our orbit. Yet he says nothing of the contempt in which he and Nixon held the Japanese, nothing about Nixon’s attack on Japan’s favorable balance of trade with the United States and his decision to keep the Japanese in the dark as he negotiated detente with China--which did more to fray Japanese-American ties than anything since the end of World War II. These “Nixon” shocks of 1971 alerted the Japanese to the tenuousness of their political and economic security.

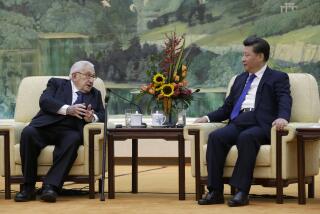

And then there is China, the country Kissinger and most other foreign affairs analysts see as the most likely rival to the United States in the 21st century. He credits himself and Nixon for the American opening to China “in the absence of any groundswell of demand,” a disingenuous remark that neglects to note that elite opinion had long favored the opening and that fear of the red-baiting Nixon had been one of the principal restraints on his predecessors. Equally slippery is his implication that the Clinton administration is responsible for growing tensions in Chinese-American relations. Kissinger is less offended by China’s brutal actions against Christians, Tibetans and pro-democracy activists than by Clinton’s pathetic efforts to modify Chinese behavior. In Kissinger’s world view, the exercise of power in the interests of the state often inflicts pain on those who offend it. He and Nixon were responsible for many more deaths in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam and shrugged off countless others in Chile and East Pakistan. In this instance, Kissinger’s dictum that the internal affairs of a state are subordinate to geopolitical considerations informs his analysis: Clinton and his aides had no business allowing distaste for China’s domestic repression to trump the strategic need for amicable relations with Beijing. As though it were a condemnation (and as if he had never heard of Sen. Jesse Helms [R-N.C.]), Kissinger holds the American left responsible for making human rights and the promotion of democracy the main priorities of American policy toward China.

Carefully, Kissinger explains that containment of China is not an option; that the necessary allies are not available; that European traders would hasten to undermine it. He argues, reasonably, that China does not seek hegemony over all of Asia but is less forthcoming about Chinese ambitions in East Asia.

When he turns to the Taiwan issue, he is simply outrageous. He testifies that even as he opened relations with Beijing in 1971, he and Nixon had great sympathy for the efforts of the people of Taiwan to create a democratic basis for autonomy. That sympathy, however, did not prevent Nixon from assuring Chou En-lai that the United States considered Taiwan part of China. In the Shanghai Communique of 1972, he finessed the issue by acknowledging that Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Strait contended there was only one China, but he neglects to note that with the end of the Kuomintang dictatorship in the 1980s and the emergence of a democratic polity on Taiwan, the island’s people increasingly reject the idea of one China.

Kissinger recognizes the danger inherent in the Taiwan issue: If the United States abandons the “one China” policy that he fashioned, war with China is probable. He warns the Chinese not to force the issue militarily but insists that it is Taiwan’s leaders who must show restraint. Again, his geopolitical approach demands that minor states appease major ones, and it is not the role of the United States to side with the weak, Taiwan’s democracy notwithstanding.

His discussion of European affairs, on the other hand, is hardly provocative. A more active role by the European Union is to be welcomed, provided it acts in ways to strengthen rather than weaken NATO. The French annoy him with their inability to conceive of their national identity in terms other than in opposition to the United States, undermining American policy at every opportunity. And yet they somehow seem confident that no matter how obstructive they are, Uncle Sam will ride to their rescue once more.

Kissinger’s indifference to domestic social conditions, at home as well as abroad, is epitomized by his approach to national missile defense. He is persuaded that technical obstacles to a missile defense system can be overcome and suggests it would be unconscionable not to build one and protect the American people from a missile attack. He concedes that creating such a system could provoke an arms race but concludes that even if a potential enemy could afford to build enough weapons to overwhelm it, the United States would be no worse off than before. He simply ignores the social cost of pouring billions into a questionable defense. He cannot understand people who would rather use the money or some small part of it to correct what he calls an “allegedly” inadequate system of medical insurance. When he engages the issues of globalization, he believes that in the long run this is a tide that will lift all boats. He notes the opposition to globalization--the demonstrations against the World Trade Organization and the World Bank--and warns that something must be done to address the criticism. American environmental and labor standards should not be imposed on developing countries, but he concedes that there must be better protection of workers and the environment. Some sort of sop must be thrown to the opposition lest it become more radical. He can already sense the presence of some of those “familiar leftist, anti-American and anti-capitalist” types he remembers from the 1960s and 1970s.

No one should be surprised that Hitchens despises Kissinger or that Kissinger is obsessed with geopolitical considerations. The question that must be answered is how, in the 21st century, will the enormous power of the United States be used.

Kissinger takes as his text John Quincy Adams’ famous explanation of why the United States would not aid Greeks fighting for their independence in the 1820s. Adams left no doubt that Americans sympathized with those who sought freedom and independence all over the world, but this country would not go abroad “in search of monsters to destroy.” Adams’ position was eminently sensible, for the United States of 1821, the kind of “pissant country” that Lyndon Johnson would have disdained. A third-rate state, unable to project what little power it had, stayed home and decried the existence of evil in the rest of the world. Is that a suitable policy for the United States 180 years later? Doesn’t the United States, as the world’s greatest power, have a greater responsibility to attempt to right the world’s wrongs than it did almost 200 years ago? Surely Kissinger’s conception of the national interest is inadequate for the 21st century. Perhaps he would benefit from conversation with Vaclav Havel, Kim Dae Jung or Aung San Suu Kyi, some of his fellow Nobel laureates.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.