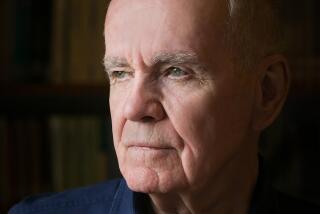

Donald Cram; Creative UCLA Chemist, Nobel Prize Winner

- Share via

Donald J. Cram, a Nobel Prize-winning UCLA chemist who may be best remembered for his classic chemistry textbook for undergraduates, died Sunday of cancer at his home in Palm Desert. He was 82.

A prolific scientist who almost single-handedly created two fields of chemical research, Cram was also a gifted lecturer who taught thousands of UCLA undergraduates and whose texts were read and studied by tens of thousands. Many UCLA students have fond memories of Cram, wearing his trademark bow tie, playing his guitar and singing folk tunes in class as the semester end neared.

“Don’s brilliant creativity, integrity and enthusiasm for life and science have forever changed teaching in organic chemistry and altered the shape and substance of the chemical research frontier,” said UCLA chemist M. Frederick Hawthorne.

Cram also played his guitar on San Onofre’s Old Man’s Beach, where he was just another surfer dude known to members of the San Onofre Surfing Club as Crambo. He was also addicted to skiing and mountain climbing--sports that, like surfing, are dangerous and romantic.

Cram shared the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1987 for creating the field known as host-guest chemistry. The goal was to mimic the interaction between enzymes and their substrates in a living cell by producing large molecules that would bind selectively with smaller ones in a process analogous to the mating of a lock with a key.

“If you can mimic a reaction that occurs in a cell, then you can understand it,” he said. “And if you understand that reaction, you begin to understand yourself.”

The unusual molecules have since become widely used in sensors, electrodes and molecular traps.

Cram also won the National Medal of Science in 1993 for his work in host-guest chemistry, as well as numerous other awards. In 1998, he was ranked among the 75 most important chemists of the past 75 years by Chemical and Engineering News, a publication of the American Chemical Society.

After winning the Nobel at the age of 68, Cram embarked on an extension of his original work that he called “carceplex” chemistry. The term describes a process in which one molecule (a carcerand) traps another inside it, thereby creating a new phase of matter. A radioactive atom, for example, might be trapped within a larger molecule that would transport it to a tumor without allowing it to come into contact with other tissues.

Cram was born in Chester, Vt., in 1919, the son of Scottish and German immigrants. His father died when Donald was 4.

As an adolescent in Brattleboro, Vt., he tried just about every odd job available, from picking fruit to painting houses. He bartered 50 hours of lawn mowing for one hour of dentistry, emptied ashes and shoveled snow for piano lessons. “By the time I was 18, I must have had at least 18 different jobs,” he said.

He learned not only about hard work and discipline, but also about creativity and the best use of time. “I’m not all that bright,” he claimed in his typical self-deprecating manner. “Mainly, I’m creative, and I’m also single-minded. If I become interested in something, I stick to it.”

Cram studied chemistry as an undergraduate at Rollins College in Winter Park, Fla., becoming known for building his own laboratory equipment. His professors wrote letters of recommendation to 17 graduate schools, but he was accepted by only three, ultimately attending the University of Nebraska, where he received a master’s degree.

“Ironically, I have since lectured at every one of those schools, and I delight in reminding them that they turned me down for graduate study,” he said.

After doing wartime research on penicillin at Merck Laboratories and receiving his doctorate at Harvard, Cram joined UCLA in 1947. He called it an instant fit. “I grew up with a provincial school that went on to become a fine national university,” he later said.

During his four decades at UCLA, Cram published more than 400 research papers and seven books. The best-known volume is “Organic Chemistry,” published in 1959 with George S. Hammond of Caltech.

Known as “Cram and Hammond” to generations of students, the book was the first organic chemistry text to be organized in terms of reactions rather than classes of chemicals.

It has gone through multiple editions, been translated into 11 languages and is still used at many schools.

Cram is survived by his third wife, Caroline, and sisters Margaret Fitzgibbon and Kathleen McLean.

He once said he chose not to have children “because I would be either a bad father or a bad scientist.” His students at UCLA, he said, are his children.