Bin Laden Deputy: Brilliant Ideologue

- Share via

MAADI, Egypt — The doctor once ran a flourishing medical clinic in this wealthy neighborhood of grand villas and trendy art galleries.

He was a scion of one of Egypt’s most respected families, a graduate of an exclusive preparatory school, a learned scholar, accomplished surgeon and poet.

But that was long ago, when the world seemed a less threatening place and the doctor worked more to heal than to hate.

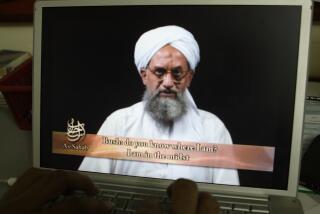

Now Ayman Zawahiri is the world’s second-most-wanted man.

The 50-year-old Egyptian is believed to be Osama bin Laden’s most important aide. Earlier this year, he was even mentioned as the next leader of the Al Qaeda terrorist network after reports surfaced that Bin Laden was suffering from kidney disease.

Zawahiri is a brilliant and forceful intellect, the man who provides much of the ideological and strategic grounding to Bin Laden’s war against the West, according to friends, family and terrorism experts.

He also brings experience. Zawahiri’s terrorist record dates back more than 20 years. He faces a death sentence in Egypt stemming from his role as leader of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, a terrorist group responsible for the 1981 assassination of President Anwar Sadat.

Zawahiri has been indicted as one of the key planners of the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. Interpol recently released a worldwide alert for his arrest.

Zawahiri’s long, slow rise illustrates the ideological evolution of Islamic fundamentalists’ struggle. Under his leadership, fundamentalist groups moved from attacking supposedly corrupt Arab governments to targeting civilians on U.S. soil.

His life also serves as a warning of the difficulties ahead as the U.S. embarks on its war against terrorism. Anti-American sentiment among Bin Laden’s top followers runs deep. Eradicating it will not be easy. Or quick.

“Feelings of hypocrisy and lack of justice and democracy and freedom--this makes people angry. This makes you bitter against everyone,” said a Zawahiri schoolmate and family acquaintance who, for safety reasons, did not want to be identified. “You become hateful to everybody.”

Zawahiri was born in Cairo in 1951 to a family of doctors and scholars.

His grandfather was the grand imam of Al Azhar in Cairo, one of the most important mosques in the Arab world and a center of Islamic thought. A great-uncle was the first secretary-general of the Arab League. Another great-uncle is one of the leaders of an important opposition party in Egypt.

Zawahiri became involved from an early age with the Muslim Brotherhood, a nonviolent group seeking the creation of a single Islamic nation built from the Arab states.

The Egyptian government, which saw the group as a threat to statehood, outlawed it in 1954. In the years that followed, hundreds of followers were imprisoned. Many were tortured, then executed.

In a response to the crackdown, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad was founded in 1973, dedicated to the violent overthrow of Egypt’s secular government through the assassinations of high-ranking officials.

“Every action has an opposite reaction,” said Fahim Huweidi, a writer for Al Ahram, Egypt’s semiofficial newspaper. “They learned a lesson from the years when their fathers and relatives were tortured and hanged and spent years in jail.”

The group had its greatest success in 1981, when several Jihad members disguised as soldiers shot and killed Sadat during a military parade. Zawahiri was picked up in the mass arrests that followed and was charged with conspiracy.

At the time a low-ranking member of the Jihad, Zawahiri was exonerated of that charge but found guilty of carrying an unlicensed pistol. He served three years in prison.

Television footage at the start of the trials gave a hint of his growing leadership role. Zawahiri appeared with other conspirators angrily denouncing the government. They grew quiet as he began speaking from behind bars in a cell crowded with other men.

“We are Muslims who believe in our religion,” he shouted at the cameras in accented English. “We’re trying our best to establish an Islamic state and Islamic society.”

After his release in 1984, Zawahiri opened a medical clinic in the Cairo suburb of Maadi, once the location of choice for British bureaucrats during colonial times and now the center of the American expatriate community.

There he treated patients from some of Egypt’s wealthiest families and cared for his own family.

His great-uncle Mahfouz Azzam, vice president of the opposition Labor Party and a criminal attorney, described him as a devoted family man, with a wife and several children.

‘He Was a Very Good Family Man’

“He’s a decent fellow. He has always been a loving person. He never in his life evoked a clash with another,” Azzam said. “He was a very good family man, very polite and very sensitive.”

Zawahiri did not stay put for long. He left his clinic in about 1985 to join the Red Crescent organization treating U.S.-backed guerrillas battling the Soviet Union in Afghanistan. He came back once, Azzam said, then left again in 1986, never to return.

“Nobody in the family has heard from him since,” Azzam said.

It was in Afghanistan and Pakistan, working under primitive conditions (his uncle said Zawahiri had to use honey to sterilize wounds) that he apparently met Bin Laden, who was recruiting and organizing guerrillas.

Both men were wealthy; both were from famous families in their homelands; both had been educated at top private schools.

Their friendship deepened in the dusty battlefields of Afghanistan and border towns of Pakistan. It was during this time in the late 1980s and early ‘90s that Zawahiri apparently solidified his idea of exporting and expanding terrorism.

He convinced Bin Laden of the need for armed action to establish Islamic states in other Muslim countries. One associate told Al Sharq al Awsat, the influential Saudi-owned newspaper in London, that Zawahiri gained great influence over Bin Laden.

Zawahiri “is what the brain is to the body with regard” to Bin Laden, Muntasir Zayyat, an attorney who defended Zawahiri on terrorist charges in Egypt in 1999, told the newspaper. A military court sentenced Zawahiri to death in that trial.

“He was able to reshape Bin Laden’s thinking and mentality and turn him from merely a supporter of the Afghan jihad to a believer in and exporter of the jihad ideology,” Zayyat said.

By the early 1990s, Zawahiri was hard at work to expand the resources and scope of Egyptian Islamic Jihad. He was using false identities and traveling throughout Europe.

In 1991, he made at least one fund-raising trip to California. Using a false identity as Dr. Abdel Muez, Zawahiri visited three mosques, claiming to be raising money for Afghan widows, orphans and other refugees.

In 1993, he was kicked out of Pakistan by the government of Benazir Bhutto, according to Yasser Serri, an Islamic activist in London who has been sentenced to death in Egypt for his alleged role in a failed 1993 Jihad assassination attempt of Bhutto, who was then prime minister.

After that, Zawahiri fled to Sudan, Serri said, to join Bin Laden’s growing forces. One report had him in Bosnia at the time to support Muslims fighting Serbs there.

“People speak about him going to Sudan or Afghanistan. It’s just not easy to be sure what he was doing,” said Diaa Rashwan, an expert on fundamentalists at Cairo’s Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies.

Terror Campaign Intensified in Egypt

One thing is clear: By the early 1990s, Zawahiri was in charge of a rejuvenated Egyptian Islamic Jihad, which had embarked on a ferocious terrorism campaign against the Egyptian government.

The group claimed responsibility for the failed assassination attempts against Interior Minister Hassan Alfi in August 1993 and Prime Minister Atef Sedki in November 1993. It also took responsibility for bombing the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad in 1995.

But it wasn’t until 1998 that Zawahiri leapt from the shadows.

In February of that year, he joined Bin Laden in declaring a new alliance to fight against the West.

“Zawahiri joined Al Qaeda because he believes in it and it is in line with his own philosophy,” Serri said. “He believes that U.S. policy is causing a lot of problems in the Middle East and Islamic countries.”

Federal court records in New York on the African embassy bombings in August 1998 document Zawahiri’s alliance with Bin Laden and his effort to recruit and raise money in the United States.

Ali Mohammed, an Egyptian-born soldier who served in the armies of the U.S. and Egypt, declared in court last Oct. 20 that Zawahiri twice traveled to the U.S. in the early 1990s “to raise funds for the Egyptian Islamic Jihad. I helped him to do this.”

Mohammed, who was pleading guilty that day to charges of conspiring to kill Americans and destroy U.S. buildings in the embassy bombings, said he also arranged security for a meeting in Sudan between Bin Laden and the leaders of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah and the Iranian government in late 1994.

After the bombings, the U.S. struck back with cruise missiles. Zawahiri was undaunted. Speaking by satellite phone, he told a Times reporter that further attacks lay in the future.

“The war has just started. The Americans should wait for an answer,” Zawahiri said then. In the spring of 1999, he was tried in absentia in Egypt for a variety of terrorist acts, including an attack against the U.S. Embassy in Albania that never materialized.

But Zawahiri’s alliance with Bin Laden proved especially controversial. There was an internal dispute within the Jihad, and now some believe the group has splintered, with no more than a few dozen still attached to Zawahiri.

Earlier this year, several leading members of the Jihad expressed their disappointment at Zawahiri’s decision to join Bin Laden, saying the choice was a strategic mistake that increased law enforcement pressure.

Though Serri denied rumors of a breakup, Rashwan said “several hundred” Jihad members decided to remove Zawahiri from a leadership position, leaving him with only a handful of disciples.

Still, experts say, those few followers are important. Zawahiri brings the Egyptian Islamic Jihad name, famous throughout the dark corners of the terrorist world, as well as expertise in carrying out terrorist attacks, especially car bombings.

Zawahiri Is Believed to Have Fled Afghanistan

Zawahiri’s whereabouts are a mystery. The Interpol arrest warrant suggests that at least some officials may believe he has already fled Afghanistan on one of his many fake passports.

Equally mysterious is whether he played any role in the Sept. 11 attacks. Family and friends deny that Zawahiri would attack civilians. They point out that the Jihad, unlike another Egyptian terrorist group, the Gamaa al Islamiya, confined its targets to political officials.

Zawahiri’s sister and mother still live in Cairo, in a bottom-floor apartment in a once elegant neighborhood that has fallen on hard times. The front of the apartment is now a kabob stand. A woman sells live chickens from a stall across the street, nearly choked by Cairo’s ever-present dust and sand.

An English-speaking woman in the apartment declined to be interviewed. She told a visiting reporter to leave.

“I have no answers to your questions,” the woman said.

*

Times staff writer Mark Fineman in New York and special correspondent Hany Fares in Cairo contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.