Black Hole Is Seen in Action for First Time

- Share via

A powerful X-ray telescope has captured the super-massive black hole in the center of our Milky Way galaxy in the act--the act of snacking.

For the first time, astronomers have observed a sudden and powerful X-ray flare coming from the direction of the voracious black hole. They believe the X-rays burst forth as the black hole gobbles up matter that comes near it.

Scientists have theorized for years that a huge black hole lurks at the center of the Milky Way--indeed that black holes lie at the center of most galaxies. The new observations provide important proof that those theories are correct.

That is an important validation for how physicists understand the universe, said Fulvio Melia, an astrophysicist at the University of Arizona who was not directly involved with the new research.

“Modern physics doesn’t have a theory that could account for this object if it is not a black hole,” Melia said.

Scientists now believe that massive black holes are common in our universe. Still, they remain exotic and little understood.

Our local black hole “is the only one we can study up close and personal,” said Mark Morris, a professor of astronomy at UCLA. Morris, who has studied the galaxy’s center for a decade, is a co-author of the new report, which is being published in today’s issue of Nature.

Physics theory holds that when enough matter is crammed together in a small enough space--by a huge star collapsing in on itself, for example--the force of gravity causes the matter to become denser and denser. Eventually, the matter becomes so dense, and its gravity so strong, that not even a beam of light can escape. The result is a black hole.

The hole is surrounded by a mysterious boundary, or membrane, that scientists call the event horizon. The event horizon has been characterized only theoretically, but it can be described in simple terms, Morris said. It is an imaginary surface that separates the inside and the outside of the black hole; anything that crosses it also crosses a point of no return and will never be able to escape the black hole.

The new observations mean astrophysicists for the first time can probe near the event horizon.

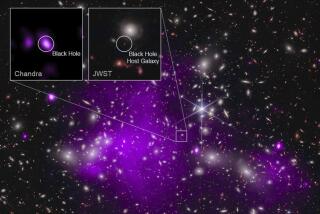

The observations were made using NASA’s 2-year-old, $1.5-billion orbiting Chandra observatory, the world’s most powerful X-ray telescope.

Two years ago, the same group of astronomers had pointed the telescope toward the center of the galaxy in hopes of observing the black hole. That observation was the first detection of X-rays emanating from a black hole, but the intensity of the X-rays was less than the powerful fireworks scientists had expected.

“We were disappointed,” said Gordon Garmire, a member of the team from Penn State University. “It was giving out the energy of only one sun when it could have been spitting out the energy of millions of suns,” he said.

This time, however, when they turned Chandra toward the center of the galaxy, they found an X-ray flare that burned brightly and receded in a matter of hours.

“It suddenly started belting out a great deal of energy, 40 times as bright as our sun,” Morris said.

“This is extremely exciting because it’s the first time we have seen our own neighborhood super-massive black hole devour a chunk of material,” said Fred Baganoff, an astronomer at MIT and the report’s lead author. “It’s as if the material sent us a postcard just before it fell in.”

Theorists who are just learning about the observations are divided on what exactly is causing the flares. Many think it is some combination of sudden heating of gas as it enters the black hole and the vagaries of the unstable magnetic fields that interact with the hot gas at the hole’s event horizon.

While there is an abundance of theories, astronomers have only a hazy idea about what happens to matter as it approaches and then surrenders to the event horizon.

“Black holes are simple objects,” Morris said. “What’s complicated is what happens to matter that falls into black holes.”

In April, the team plans to point Chandra back toward the black hole in hopes of determining whether flares are common or rare events.

“Do these things happen all the time or were we the luckiest people in history” to capture a rare event in a few hours of viewing time? asked Morris.

The black hole is 24,000 light-years from Earth. According to observations of stars swirling rapidly around the black hole, it packs the mass of 2.6 million suns into an area smaller than our solar system.

“We always thought our Milky Way was a benign place,” said Alan Bunner of NASA. “Well, maybe not.”