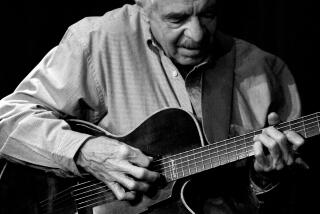

Joe Lovano Lives Up to the Critical Acclaim

- Share via

A year and a half after the album was released, Joe Lovano showed up at El Camino’s Marsee Auditorium Saturday night with a program dominated by music from his “52nd St. Themes” CD. Why the delayed appearance? Don’t ask. Jazz has never been known for its capacity to follow the usual norms of commercial promotion.

What mattered, in any case, was the quality of the music, rather than the timeliness of its presentation. Lovano may be the most critically praised tenor saxophonist in jazz these days, and with good reason.

Starting with Sonny Rollins as a foundation point, he has developed a voice of his own, extending his musical range into strikingly contemporary areas. And Saturday, as on previous appearances in the Southland, his playing seemed up a level from past performances--clear evidence of an artist still fervently in pursuit of his creative muse.

It also helped that Lovano’s Nonet essentially consisted of a group of all-star players. Steve Slagle, alto saxophone; Ralph Lalama, tenor saxophone; Gary Smulyan, baritone saxophone; Conrad Herwig, trombone; Barry Reese, trumpet; John Hicks, piano; Dennis Irwin, bass; and Lewis Nash, drums, are among the music’s most talented musical adventurers.

Given plenty of space to stretch out in a program dominated by Tadd Dameron classics such as “If You Could See Me Now,” standards such as “Embraceable You” and the bebop energies of “Hot House,” they delivered compelling solo after solo.

Predictably, Hicks was a wild man, his inimitable efforts ranging across the keyboard, pounding rich chordal clusters, using the instrument’s full selection of timbral possibilities. And Nash, both as a rhythmic engine for the music and as a stellar soloist, was a constant center of attention, especially effective during a lengthy drum and tenor saxophone duet with Lovano.

That said, however, the surprisingly short program (barely 75 minutes long) had its inconsistent moments, primarily as a result of the stylistic contrast between the bebop era arrangements of Willie “Face” Smith and the far more contemporary attitudes of most of the soloists. Revivals are always tricky, and Lovano should be praised for his desire to express his love for bebop, in general, and the music of Dameron, in particular. But there were too many moments in which wild-eyed, contemporary stretching out simply seemed out of sync with the rhythmic and harmonic specificity of the program’s ‘50s-style orchestrations.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.