Young Warriors and the Age-Old Lessons of Combat

- Share via

They slid from a helicopter five stories to the ground, dropping like tethered birds of prey and scattering in directions of the storm winds that blew around them.

Once on the ground, they turned from the “tether”--a rope dangling from above--to face unseen enemies, guerrilla fighters as invisible in practice as they might be in reality.

Then they returned to await their turn to do it again, and again and again.

The scene was an open field at Camp Pendleton, a sprawling military complex of 125,000 acres just north of San Diego, home of the storied First Marine Division.

The large gray helicopter, its twin rotors stirring up the hurricane of wind and dust, hovered over the field, and from its opening came the “birds”--young camouflaged warriors practicing the techniques that they could be called upon to employ under hostile conditions.

The exercise was performed for the media as a way of demonstrating the capabilities of these “new” Marines to strike with the speed of cobras in areas of combat where large forces can’t operate.

For instance, in Afghanistan.

We were there with our cameras and our notebooks watching as the young men, mostly in their early 20s, fast-roped and then rappelled from the belly of the chopper in the storm-wind setting.

And we listened to them boast, as young warriors will, that they were ready for anything. As they spoke, we could hear the chatter of small arms fire somewhere and the distant boom of artillery, underscoring their bravado.

It was all so familiar.

This was routine training, but there was nothing routine about the situation that has suddenly placed this 60-year-old camp on high alert. Terrorism was on everyone’s mind, and the young warriors were edgy.

“When Bush says go, we go,” one Marine said, crouched on the edge of the field, watching the Sea Knight helicopter circle over the dry hills to return for another drop. “That’s why they call us the 911 Force.”

“But our families worry,” said another, adjusting the vest that held his combat gear, everything from ammo to a first-aid kit. “My mother keeps calling.”

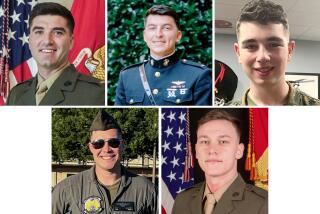

Their names are Guesta, Ward, Mayfield and McKinley. Furlong, Grasmuck, Rackley and Lawler.

They come from Alabama, Michigan, Florida, Texas, California and New York. Three of them are from the same hometown. All bear the military occupational specialty number 0311, the MOS of basic infantry, backbone of the Marine Corps.

“They’re ready all right,” an instructor said as he stood over a group of 10 Marines who knelt in the dirt, waiting for the helicopter to return.

His name is Sgt. Thomas Quinn. He has trained 250 men over the past year to drop from the sky in an exercise of quick deployment.

“I sign their ‘graduation’ cards,” he said. “That makes me responsible for seeing that they’re ready when they leave here. Their lives are in my hands.”

The big chopper settled into the dust storm. “All right,” Quinn shouted over its roar, “let’s rock and roll!”

The machines of war are large. The helicopter, an ancient cargo carrier, seemed to dominate the sky it occupied. The deep thrump-thrump-thrump of its rotors and the overpowering smell of its aviation fuel filled the senses.

In battle, tanks join the chaos, bombs explode, machine guns fire and men shout to be heard above the roar. Confusion often replaces the precision refined in training, which is why special units, such as Marines, train so hard.

But there is no way to accurately duplicate war in a camp-based exercise. Combat introduces variables that can never be anticipated. The machines seem even larger in a battle, more awesome and dangerous. And one realizes, amid the smoke and the noise, that humans are the most fragile elements of the fight. We are the heartbeats in the steel.

I said this all seemed familiar. I trained at Pendleton a half-century ago. We climbed up and down the sides of ships back then; troop carriers anchored off the coast. We trained out of foxholes and charged up hills with bayonets. We anticipated hitting the beaches or taking the high ground, not dropping like eagles from the sky. Combat helicopters came later.

It’s a different Marine Corps today in some ways, but in other ways the same. We, too, were 20 and 21. We, too, knew we would be sent overseas to fight. Camp Pendleton was as tense then as it is today, but we felt ready. We boasted. We were, after all, Marines.

But how different it was when we got there.

Guesta, Ward, Mayfield, McKinley. Furlong, Grasmuck, Rackley and Lawler.

If they only knew.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.