A.T. Goins, 87; One of Few to Survive White Mob’s 1923 Rosewood Massacre

- Share via

A.T. Goins, one of the few survivors of the 1923 massacre by a white mob in the small Florida town of Rosewood that left the predominantly black community in ruins, has died. He was 87.

Goins, who was awarded $150,000 in compensation by the Florida Legislature in a highly publicized fight in 1994, died March 24 in St. Petersburg. The cause of death was not announced.

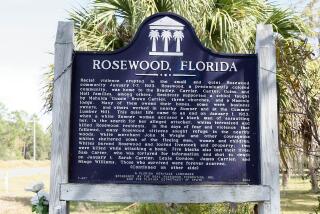

The massacre, documented in the 1997 movie “Rosewood” from director John Singleton, began on Jan. 1, 1923, when a white mill worker’s wife in the nearby town of Sumner claimed that she had been attacked by a black man.

A posse was formed to search for the assailant and went straight to Rosewood, a community of perhaps 200 residents.

When no suspect was found, the posse turned into a vigilante mob, pulling blacks from their homes and burning structures. The siege went on for six days and the mob grew in size, eventually numbering as many as 300 people.

While the official death toll was six blacks and two whites, black descendants of Rosewood have alleged that many more were killed and their bodies hidden in mass graves.

Three days into the siege, the mob came to the home of Sarah Carrier, one of Rosewood’s leading residents. The mob had called for Carrier to come out of her house and she refused. Goins, Carrier’s grandson, was 8. He was hiding upstairs with several other children.

In testimony to the Legislature, Goins recalled the assault on the house.

“Grandma didn’t want to go out, so the mob just started shooting in the house,” Goins said. “Grandma got hit in the head with a bullet.”

Goins’ grandmother was killed. So were two members of the mob, who were shot by Sylvester Carrier, Sarah Carrier’s son, as they tried to enter the house.

“They bust right in that front room and came right into the hallway,” Goins said.

Goins and several other children escaped from the house and were led by an adult to safety in the nearby woods.

A train eventually came and took the survivors of the attack--mostly women and children--to Gainesville. Goins said that he believed the train was sent by a white businessman who had dealings with the people of Rosewood.

Black descendants of Rosewood maintained that the attack on the mill worker’s wife was carried out by the woman’s white lover, a railroad worker, and that she made up the story of the racial attack in an attempt to save her marriage.

Goins said that his sister told him she had seen the woman’s attacker. “My sister said she seen this man go out and step across the fence,” Goins said. “She said it was a white man.”

The survivors of the Rosewood massacre fled to various parts of the state. Goins returned briefly to the area as a teenager when he was playing for a baseball team.

“That was the last time I’ve been to Rosewood,” he told the St. Petersburg Times some years ago. “I don’t want no part of Rosewood.”

All the survivors kept quiet about the events, fearing repercussions.

That silence lasted until the early 1980s when a reporter for the St. Petersburg Times happened upon the area near Rosewood and asked residents why the area was all white. Shocked and intrigued by the answer, reporter Gary Moore spent the next two years searching for survivors and piecing together the Rosewood story. A segment of CBS’ “60 Minutes” later explored the massacre and the long-buried secret.

By the early 1990s, there were calls to provide survivors of the massacre and their descendants with restitution for their suffering.

The state Legislature appointed a team of scholars from several Florida universities to investigate the claims. The scholars determined that police in Rosewood “failed to control local events” and failed to contact the state government for help. Despite some legislators’ reservations, administrative analysts recommended that damages be paid.

Each of the eight known survivors was awarded $150,000. Another $500,000 was designated for families that lost property in the massacre and a $100,000 fund was established for minority scholarships.

Goins is survived by his wife, Anna Maude, a sister and nine grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.