China’s Antibiotics Breeding Trouble

- Share via

YANDIAN, China — Most of the people who come to Dr. Wang Yuhua’s unheated rural clinic in central China have minor complaints--runny noses, sore throats, maybe a fever.

For 1.4 yuan, or just 17 cents, Wang injects them all with penicillin and sends them on their way. Empty drug vials quickly fill the bucket under his unpainted wooden desk.

While antibiotics like penicillin have done wonders to improve health in China, experts say the drugs are being overused, leading to the emergence of drug-resistant diseases. The problem is being seen in many countries, but the experts warn that China is becoming a particularly serious breeding ground.

“Overuse is causing penicillin and other antibiotics to lose their medical value. Doctors give them for coughs and sore throats without even bothering to learn the cause” of the illness, said Wang Hui, deputy director of bacteria research at Beijing Concordia Medical School.

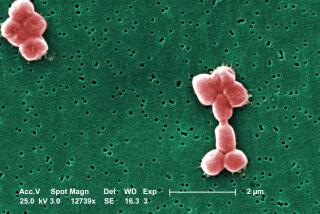

Antibiotics save countless lives by killing bacteria, the cause of infections and deadly illnesses. But the more these drugs are used, the greater chance of a genetic mutation that allows bacteria to protect themselves. Drug-resistant strains then flourish as antibiotics kill off other bacteria that compete for food.

Although stronger strains are appearing worldwide, experts say China is especially troublesome because of its huge population, the ready availability of antibiotics and lack of awareness about the problem.

“China is among the leading countries that are a concern,” said Dr. Stuart Levy, a Tufts University expert on drug-resistant infections. “The situation is terrible because these drugs are essentially available over the counter.”

Resistant strains are being discovered in China at an alarming rate.

A survey last year in the central province of Hubei found that 60% of large intestine infections could not be stopped by ciprofloxacin, a common antibiotic best known as a cure for anthrax. No such infections were found in 1993.

A quarter of China’s 5 million reported tuberculosis cases were infected with strains that can survive one or more antibiotics, the Beijing Youth Daily reported last April.

More ominous, hospitals in Hubei and elsewhere reported a rise in “super strains” of the bacteria MRSA able to resist several antibiotics.

Things could get worse as antibiotics lead to ever tougher bacteria, which in turn require stronger drugs, health officials say. The result could be bacteria that survive all drugs, making routine surgery dangerous by threatening incurable infections.

“Overuse of antibiotics is like wasting the lives of your own soldiers in a war. Eventually you’ll have too few left to beat the enemy,” said Shen Zhengyi, who heads Hubei’s Bacterial Resistance Monitoring Center.

More than 70% of drug prescriptions nationwide in China are for antibiotics, compared with about 30% in the West, Shen said.

In addition, 6,000 tons a year are fed to livestock, finding their way into milk.

Experts say Chinese health workers have only rudimentary medical training and often don’t know the dangers of overuse of drugs. Health workers say they are only beginning to be made aware of the problem, and few government policies exist to curtail antibiotic use.

The financial incentive to over-prescribe drugs is another problem. Drugs are one of the few health costs not controlled by the government, making them an inviting revenue source for medical workers.

But the biggest reason for China’s fondness for antibiotics may be their proven success.

In Yandian, the village in Anhui province where Wang’s clinic is located, antibiotics have slashed disease rates over the last decade. Children are now two-thirds less likely to die before age 5 as they were in 1990.

“Antibiotics are advanced Western medicine. Everyone who comes in here wants them,” Wang said.

Experts fear that misuse of antibiotics will increase as lower costs and rising incomes put them within reach of even poor households.

Li Jiawen’s three-room farmhouse in Pingtang, a village near Yandian, has dirt floors, mud walls and only two naked bulbs for light. But on the crude wooden shelves in the main room are piles of white packages containing oral antibiotics for his father’s tuberculosis.

The pills cost about 12 cents each--well within the means of his family’s income of $700 a year.

“I want the best I can afford for my father,” Li said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.