City of Hope Rests Its Case on Genentech

- Share via

City of Hope National Medical Center rested its breach-of-contract case against Genentech Inc. on Friday. The company is accused of failing to pay $445 million in royalties on a City of Hope invention that launched the biotechnology revolution.

This is City of Hope’s second try for a verdict. The first trial ended with a hung jury in October.

The dispute centers on a 26-year-old contract between the hospital and Genentech that established a profitable collaboration.

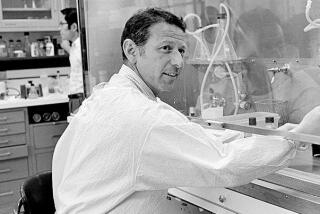

In 1976, Genentech agreed to fund work by City of Hope scientists Arthur D. Riggs and Keiichi Itakura. The company also agreed to pay the hospital royalties on products that resulted from the scientists’ work. City of Hope, in turn, agreed to give Genentech the patents on any of their discoveries.

No one knew what to expect from the contract at the time. However, it led to a discovery by Riggs and Itakura that made it possible to mass produce human proteins, such as insulin, to treat disease. Their invention--a method of producing the proteins in bacterial cells--remains widely used.

Genentech obtained patents on the discovery by Riggs and Itakura, and, since 1980, has 22 licensing deals with other drug firms. City of Hope claims it is owed $445million in royalties on drugs produced under the third-party licenses. Genentech says it does not owe the hospital royalties on those sales.

Genentech, the second-largest biotechnology company next to Amgen Inc., has argued that City of Hope is entitled to royalties on only two drugs produced under the patent, human insulin and human growth hormone. The company has paid the hospital more than $285million in royalties on those drugs.

A favorable jury verdict for City of Hope, which could come as soon as next week, would arrive at an opportune moment for the Duarte-based hospital. The royalty stream under the Riggs and Itakura patents ends in 2003, when the patents expire. The hospital would have been in the red for fiscal 2001 without the $16 million in royalties it received from the patents.

However, City of Hope previously denied that the lawsuit was financially motivated.

During five weeks of testimony, City of Hope lawyers called several present and former Genentech officials as hostile witnesses in an effort to build the hospital’s case.

Thomas Perkins, a legendary Silicon Valley financier, spent two days on the stand. Perkins provided start-up funds for Genentech and served as its first chairman. He testified that he approved the 1976 contract, but could not clearly recall discussions about its terms.

Perkins, 70, said he did not tell City of Hope about third-party licenses and did not instruct anyone at Genentech to do so. He denied an implication by City of Hope attorney Morgan Chu that Genentech intended to cheat City of Hope.

Perkins told Chu it was “mathematically a true statement” that Genentech’s profit would rise if the company underpaid royalties. But when Chu asked if higher profits would boost Genentech’s stock price--and benefit Perkins personally--he responded: “You are implying a conspiracy by the board.”

Perkins on several occasions contradicted testimony he gave in depositions. He said he could now remember which drugs were covered by the contract, when in his deposition he did not know. And he recalled previously forgotten conversations about the contract with Genentech’s deceased co-founder, Robert Swanson.

Chu repeatedly pointed out the discrepancies, causing Perkins to blurt out at one point: “Your Honor, there is such a thing as remembering.”

Glenn Krinsky, general counsel for City of Hope, said he believed the contradictions undermined Genentech’s credibility.

But Sean Johnston, vice president for intellectual property at Genentech, said it is not surprising that Perkins remembered new details after seeing documents in court. Perkins’ testimony, he said “is entirely credible.”

The hospital closed its case in Los Angeles Superior Court after testimony from City of Hope scientist Itakura. Under questioning from City of Hope lawyers, Itakura described his role in the discovery. Itakura told jurors that he used chemicals to make the gene for insulin and to make a small portion of the gene for human growth hormone. A gene is a chemical recipe that tells a cell how to make a specific protein. At the time, in 1976, Itakura was among the few scientists in the world adept at building genes with off-the-shelf chemicals.

Under cross-examination by Genentech lawyer Susan Harriman, Itakura testified that Genentech scientists had important roles in the discovery.