Tenet’s Aggressive Corporate Culture Fed Crisis, Insiders Say

- Share via

Last February, more than 1,000 Tenet Healthcare Corp. employees from around the country gathered in Las Vegas to talk about Target 100, the hospital company’s quality excellence program. But to some participants, the three-day affair at Caesars Palace felt more like an overwrought company bash.

Speakers dressed up as Dr. Seuss characters. Tenet Chief Executive Jeffrey C. Barbakow, wearing a big red-and-white-striped hat, addressed the group as mayor of Tenetville, and souvenir dolls of him in the role were passed out. Senior executives rode around in decorated golf carts, and some emerged on stage as if riding Harley-Davidsons. Lip-sync artists danced to Beatles’ tunes.

It was an extravaganza befitting Vegas, and it spoke volumes about the prosperity and culture at the nation’s No. 2 hospital chain, now under intense government scrutiny. Tenet executives said the Las Vegas conference was a relatively cheap way to celebrate a highly successful program. Still, in the staid and budget-conscious hospital industry, Tenet was accustomed to pushing the envelope.

Even among for-profit hospital operators, the Santa Barbara-based company led the pack, not only with programs such as Target 100 but also in the way it raised hospital charges, rewarded hospital executives with bonuses that matched their annual salary and went after high-profit lines of medical services.

Some of Tenet’s aggressive business practices have come to light in recent weeks, as Tenet’s stock has wilted amid an audit by Medicare regulators and an FBI investigation of two doctors at a Tenet hospital in Redding.

Throughout, Barbakow has maintained that Tenet did nothing illegal, and he has blamed the company’s woes largely on a few individuals. Barbakow, 58, was brought in a decade ago to restore the company after a scandal involving its psychiatric hospitals. One of his first acts was to establish a tough ethics program for employees, which he said remains in place today.

Even so, some Tenet insiders and analysts think that the makings of the company’s current crisis stem from an aggressive corporate culture, fostered at the top, that encouraged hospital managers and others to push short-term profits to the hilt.

One prime example is how executives are paid. In Tenet’s last fiscal year, chief executives of the company’s 113 hospitals in the U.S. had an average salary of $200,000. But collectively, the company confirmed, they doubled their pay with cash bonuses, mostly for boosting their hospital’s earnings. And that doesn’t include stock options.

Major nonprofit hospitals, including Sutter Health and Catholic Healthcare West in California, generally limit incentive pay to 20% to 35% of base salary -- and growth in net income usually isn’t a factor, although making budgetary goals is. At other investor-owned hospitals, cash bonuses can run 50% to 70% of base salary, according to recruiting firm Korn/Ferry International.

Tenet’s biggest national rival and the country’s largest hospital chain, for-profit HCA Inc., said bonuses for its hospital CEOs are only in stock options. HCA spokesman Jeff Prescott said the Nashville-based company eliminated cash bonuses in 1997, shortly after it became embroiled in a massive Medicare fraud investigation. “We wanted to get rid of short-term profit incentives,” he said.

Tenet executives said their big bonuses last year reflected the corporation’s 51% jump in earnings, which the company has acknowledged were driven in good part by outsize Medicare revenue generated by rapidly raising its hospitals’ list prices.

Alan R. Ewalt, Tenet’s longtime head of human resources, said the company’s target bonus for hospital CEOs is 36% of salary and based mainly on two factors: meeting budget and measures of patient satisfaction. But they could enhance cash bonuses by raising their hospital’s operating income, with no limit to this extra income.

“The incentive plan is designed to encourage CEOs to make sure to meet business goals and get a good return to add additional capital,” Ewalt said.

And did this bonus plan put undue pressure on executives to raise their hospital charges and take other aggressive actions? “We’re going to do a review,” Ewalt said, “to see if there are those relationships.”

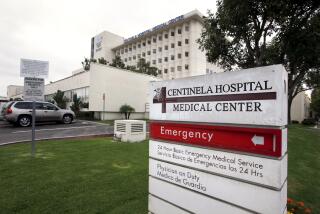

A number of Tenet hospital CEOs contacted for this story declined to comment or did not return telephone calls. In one interview arranged by Tenet, Michael Rembis, chief executive at Centinela Hospital Medical Center in Inglewood, distinguished between focusing on profit and growing the business, which he said he does. That means expanding hospital services, increasing admissions and taking care of patients.

“Even when we didn’t hit monthly targets, the company did not put a lot of pressure on me,” said Rembis, a 20-year health-care veteran. “I’ve never been asked whether we met our returns on investment,” he added, noting that Tenet has put $52 million into the facility since 1997, including building a heart center.

Centinela, a 371-bed hospital in a lower-income community, has been one of Tenet’s more profitable hospitals, based on state filings. The hospital’s pretax net income was $64.2 million for the year ended June 30, up 25% from the previous year.

But Centinela’s earnings in the last two years got a notable lift from special Medicare “outlier” payments, which are made in addition to regular fixed reimbursements and are intended to help hospitals cover the costs of complicated cases. Medicare calculates outliers by comparing a hospital’s costs with the list charges of a patient’s case.

As Tenet came under fire from regulators in recent weeks, the company disclosed that aggressive increases in hospital charges produced unusually large outlier payments. Medicare’s top official has accused Tenet of inappropriately gaming the system.

Rembis, who has run Centinela since 1999, was aware his hospital received a larger share of outlier payments than some others. But he said he had no idea how much that affected the hospital’s bottom line and that directions on raising hospital charges came from corporate headquarters. He declined to be more specific, nor would he discuss his salary and bonus.

Some current and former Tenet hospital managers painted a different picture of the financial pressures. One former senior executive of a Tenet hospital said that corporate expectations to grow earnings were intense, and that failure to make budget goals was sometimes met with a grilling at monthly meetings. Hitting financial targets, a current Tenet executive said, was “how you were judged, paid and evaluated.”

Tenet’s strategy of aggressively increasing hospital charges was aimed partly at bolstering revenue from health insurers. Like Medicare, insurers generally pay Tenet hospitals not only a fixed rate but also extra sums for costly cases, called stop-loss payments, based on a percentage of hospital charges.

This strategy “reflects a very short-term thinking of maximizing a revenue draw and not giving consideration to long-term ramifications,” said Tim Moran, chief executive of nonprofit Mercy Hospital in Bakersfield and a longtime Tenet employee who left in 1994.

In Moran’s view, as well as that of some doctors and analysts, Tenet’s business model may have encouraged hospitals to practice more aggressive medicine. If hospitals are paid a flat fixed rate, they argue, they will have incentives to manage care more carefully. But if hospitals know they are going to get paid a percentage of each procedure because the case has qualified for Medicare outlier or stop-loss payments, hospitals are likely to be less concerned financially about ordering additional tests and procedures.

Barbakow has said Tenet went too far in raising hospital charges that inflated Medicare revenue. This month, he ordered a freeze in hospital charges and said uninsured patients would receive substantial discounts. In addition, he said Tenet would move away from relying on insurance payments based on hospital charges.

But in a recent interview, Barbakow suggested that Tenet’s problems were not indicative of an aggressive business culture but stemmed largely from a failure of communication. “Certain individuals were doing things and not passing along” the information, he said. Among them, he has indicated, were Thomas B. Mackey, Tenet’s chief operating officer, and David L. Dennis, chief financial officer, who were dismissed last month. Neither responded to requests for comment.

A month before leaving, Mackey exercised $10 million in Tenet stock options. Barbakow this year cashed in stock options worth $111 million, on top of his $5.5-million salary and bonus for fiscal 2002.

Several Wall Street analysts have criticized Barbakow’s compensation, saying that itself was a statement of the company’s values. “When you pay the CEO so much money, you’re saying, ‘That’s the game. Make as much money as you can,’ ” said Clifford Hewitt, a health-care analyst at Legg Mason. “At some point there’s a spillover effect. We can’t calculate it, but this kind of excess ... gets reflected somewhere in the behavior of the organization.”

This month, Barbakow said his compensation, like many other things at the company, were on the table. “If we find that our incentives aren’t aligned in the proper way, we will address it,” he said.

Dennis Jorgensen, senior vice president of Tenet’s ethics, business conduct and administration, said what’s happened in the last two months has caused a lot of frustration and anger among employees.

“They know this is not a true reflection of the culture of this company,” he said. “I think it’s going to be a challenge ... to reestablish the reputation and trust we have.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.