Lott’s Fate Could Depend on How Southern Republicans View Him

- Share via

The most immediate problem for Sen. Trent Lott (R-Miss.) is that his career provides barrels of fuel for the firestorm he ignited with his praise of Strom Thurmond’s 1948 presidential campaign.

Over his career, Lott helped lead the fight to restore the citizenship of Jefferson Davis (the president of the Confederacy during the Civil War), opposed a national holiday honoring the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and voted against extension of the Voting Rights Act. He might explain any of those decisions individually; collectively, they suggest a longtime tendency to play with matches on race.

That history provides a context for interpreting Lott’s insistence at Thurmond’s recent 100th birthday party that America wouldn’t “have had all these problems” if the nation had followed Mississippi’s example in voting for Thurmond when he ran for president on a segregationist platform.

It’s difficult to imagine that Lott literally believes the nation, or even the South, would have been better off if segregation somehow survived. The death of Jim Crow made possible the birth of the modern South; only after segregation fell did the South rise from endemic poverty and economic isolation.

The migration, outside investment and economic development that has transformed Southern life over the last 40 years could never have occurred if the region was still marked by the stain of state-sponsored discrimination.

In that way, the gleaming office towers of Charlotte, N.C., the new factories built by BMW and other international companies along the Interstate 85 corridor in South Carolina and the bustling cosmopolitan prosperity of Atlanta and Dallas are all testament to how much the white South has benefited from the civil rights revolution. Without racial integration, the South never would have achieved economic integration. Surely, Lott understands that.

Yet Lott has said things similar enough, often enough, to suggest that he sees value in signaling sympathy for the fading few who do still believe that the South would have been better off if segregation somehow had survived. Lott made almost identical remarks about Thurmond in 1980. He maintained a longtime relationship with the Council of Conservative Citizens, an extremist white group. His first political job was as an aide to a segregationist Democratic congressman. And there is that peculiar passion for restoring the good name of Jefferson Davis.

Against the backdrop of his latest remarks, all of these decisions will be seen in a different light. Already, Time magazine has reported that Lott, as a University of Mississippi student, fought to prevent any chapter in his fraternity from admitting blacks. A week ago that would have been viewed as ancient history. Now it’s suddenly relevant. It’s a signal that this fire can burn for a very long time.

Lott’s fellow Republicans will decide how much heat they want to take. President Bush last week gave Lott a hand and a shove: The White House said the president believed Lott should remain as Senate majority leader when the GOP takes control of the chamber in January. But Bush also condemned Lott’s remarks sharply enough to encourage those hoping to force Lott out.

In his struggle to retain his position, Lott has two principal assets. One is the natural tendency of either party to rally around a leader condemned by the other. The more the Congressional Black Caucus or the big-city editorial pages call for Lott to step aside, the more many conservatives will insist that Republicans can’t let their critics pick their leaders.

Lott’s second line of defense is the primacy of the South in the modern Republican coalition. The 11 states of the old Confederacy, plus Oklahoma and Kentucky, provide the GOP’s margin of majority in the House and the Senate; rebuking such a prominent local son could ruffle feathers across a region that has become the foundation of Republican political strength.

Or, intriguingly, maybe not. It’s possible that if this controversy burns long enough, other Southern Republicans may come to view Lott as an albatross -- a throwback to morally tainted strategies they have almost entirely outgrown.

Opposition to integration and the civil rights laws was the point of the wedge that allowed Republicans, a generation ago, to shatter Democratic dominance of the South. As late as 1980, Ronald Reagan opened his general election campaign in Philadelphia, Miss., the place where three young civil rights workers were murdered in 1964, by declaring his belief in states rights -- code for which his audience needed no translation.

But such appeals to race have faded to the margins of Southern politics. No one has run a campaign stressing opposition to affirmative action since Sen. Jesse Helms (R-N.C.) more than a decade ago. Even crime and welfare, second-generation issues with racial overtones, have receded since Bill Clinton led the Democrats to the center on both fronts in the 1990s.

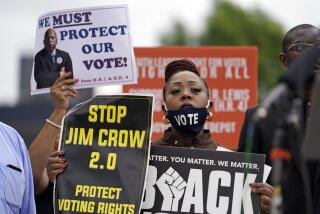

In the South, as elsewhere, race still intermittently flares -- as in this year’s dispute over the Confederate flag in Georgia or periodic Democratic charges that Republicans are trying to suppress black voting. But Republicans are long past the day when they need to manipulate white racial resentments, either overtly or covertly, to win in the South.

That’s not to say Southern political allegiance doesn’t divide along racial lines. African Americans still vote overwhelmingly Democratic in every Southern state. And Southern whites vote so strongly Republican that Democrats almost everywhere consider it a triumph to win 40% of them.

But the ties that bind Republicans to most whites in the region are conservative views on taxes, national defense and social issues such as guns and abortion, not nostalgia for Jim Crow. If anything, comments like Lott’s now probably risk losing the GOP more votes among suburban Southern moderates than they might gain in the backwoods, Emory University political scientist Merle Black notes.

Thus, the choice facing Lott’s fellow Southern Republicans. Not many Northern Republican senators can relish reappointing as majority leader a man they are unlikely to ever again feel comfortable inviting into their states. But Lott’s position probably won’t be endangered unless some of his fellow Southerners also see his old-style insinuations as a threat to the new coalitions they are trying to build.

*

Ronald Brownstein’s column appears every Monday. See current and past Brownstein columns on The Times’ Web site at: www.latimes.com/brownstein.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.