Chilean Links Ozone Loss to Skin Ailments

- Share via

PUNTA ARENAS, Chile — Jaime Abarca works alone at the end of the world. He is the only dermatologist in Patagonian Chile, a wind-swept landscape where trees grow sideways and penguins frolic in icy waters.

Those rare spring days when the sun blazes can bring fishermen into Abarca’s office with nasty burns on their cheeks. During one especially bad spring, in 1999, Abarca treated six people with an ailment he’d never seen in 15 years of practice: blistering sunburns.

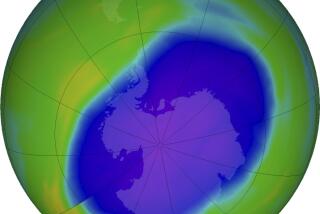

This month, Abarca and two Chilean climatologists published a paper in an American academic journal that documents what they believe are the first cases of skin ailments directly connected to the thinning of the ozone layer. The sun blisters Abarca treated in 1999, it turns out, coincided with days when the ozone hole over the Antarctic had grown large enough to float over Punta Arenas.

“The problem is eight or nine days every spring, when there is a sharp change in the weather,” Abarca said in his office at the regional hospital in this city of 123,000.

On most days, even sunny ones, residents of Punta Arenas and nearby Tierra del Fuego--the southernmost inhabited regions in the world--tend to cover themselves against the fiercely cold winds. The average summer temperature in Punta Arenas is just 51 degrees.

But when the winds die down and the clouds disappear, people start to shed their sweaters and hats. They might forget about the danger of getting burned by ultraviolet rays, despite a public notice system that warns people on days when the ozone is thinner than usual.

Abarca published his paper in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology with co-authors Claudio Casiccia and Felix Zamorano, climatologists at the University of Magallanes.

Until now, most studies on ozone layer thinning and its effect on humans have centered on statistical analyses of the increase in skin cancer rates in the middle latitudes, Abarca said.

A recent study by Chilean dermatologist Juan Honeyman found a 28% increase in conditions such as cheilitis--fissures around the mouth--over a seven-year period in the Punta Arenas region.

But no studies have provided specific evidence linking such increases to changes in the ozone layer.

Rumors of sun-related ailments in animals and humans in southern Chile prompted a team of investigators, funded in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, to travel to Punta Arenas in 1992.

A joint American-Chilean study published in 1995 found no basis for the rumors, which included stories of sheep and cattle being blinded, presumably by long-term exposure to high levels of ultraviolet radiation.

Although the study found that UV radiation in southern Chile increased as much as 2.3 times on some days, because of the shifting of the ozone hole, overall sun exposure increased only 1% a year. People in Punta Arenas are still exposed to less UV light than residents of Washington, D.C., even with the thinning ozone layer.

Abarca’s work shows a much more subtle and passing effect, tied as much to the fickle Patagonian weather and recreational habits of the residents as to the ozone layer.

During the 1999 outbreak, the two spring days with the largest ozone loss happened to come on Sundays; one was on the same day the city staged a four-hour car race. And both those Sundays had relatively little cloud cover. On the Sunday with the worst ozone loss--Dec. 5, the end of the Chilean spring--Abarca treated more sunburns in a single day--eight--than he had ever treated in a single year.

Abarca’s findings confirm what local doctors have said for years.

“People burn because they live in a culture where the sunburn has never been an everyday concern,” said Jorge Barrientos, a pediatrician. “What keeps it from being an even more serious problem is that people spend so much time indoors.”