Plan to Curb Jewelry District Hazards Proposed

- Share via

City officials Wednesday unveiled a plan to clean up environmental and fire hazards in downtown’s jewelry district, but acknowledged that the plan mostly restates or weakens current laws.

City officials--under pressure to sustain the economic life of the jewelry district--presented the guidelines at a private meeting of jewelry manufacturers, telling them that the rules were relaxed to help them stay in business.

Enforcing the “existing law would be much more stringent than the guidelines. If we cited you based on the laws that exist now, we would be much harsher,” said Tara Devine, Mayor James K. Hahn’s representative to the industry-government task force that developed the enforcement guidelines.

David Keim, the city Building and Safety Department’s head of code enforcement, called the guidelines “somewhat relaxed interpretations of the code.”

The guidelines presented Wednesday are meant to correct health and safety hazards without shutting down jewelry businesses. About 700 jewelry makers operate in high-rise buildings downtown, employing 15,000 people, according to industry estimates. The district is the nation’s second-largest jewelry manufacturing and retail zone, after New York’s.

The jewelry district has operated for decades despite being basically illegal, due to chemical and fire hazards posed by the manufacturing process. None of the 31 downtown high-rise office buildings now occupied by jewelry makers is approved to house them.

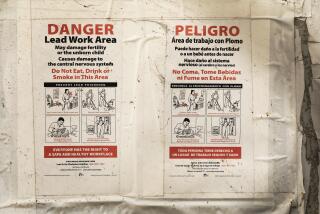

Downtown jewelry makers routinely use toxic chemicals such as cyanide as well as torches and ovens in manufacturing processes that by law are restricted to buildings rated for hazardous uses.

The guidelines will effectively legalize jewelry making by amending building laws. Jewelry making will be placed in the same category as less hazardous furniture manufacturing.

The guidelines will require manufacturers to follow many safety rules they now violate. The rules will allow some illegal practices--such as the use of torches--to continue only with new restrictions.

The guidelines resulted from a series of meetings that began in 2000 between industry representatives and government officials. The meetings were closed to the public and organized by the Downtown Center Building Improvement District, a powerful group of property owners.

Carol Schatz, who heads both the Building Improvement District and the Central City Assn., a business lobbying group, praised the guidelines as the product of “a true partnership” between business and government. “We went to the mayor’s office, they made a few calls, and the rest is history,” Schatz said of the help provided by public officials beginning in the Richard Riordan administration.

Officials said the guidelines will be phased in over the next few months. Alan Wendell of the Building and Safety Department told the industry group that an outreach program will begin in February to inform businesses of the guidelines. In March, inspections will begin to ensure that businesses are complying with the guidelines, Wendell said.

Wendell explained key guidelines to the group, including that “no untreated hazardous waste should go into the sewer system” and that an approved hazardous waste hauler should be used to dispose of toxic wastes. Responding to an audience question, Wendell acknowledged that the guidelines “come from the existing code. They are not new rules.”

Code enforcement head Keim said city officials “are hoping to get 100% voluntary compliance” from jewelry manufacturers through their light-handed approach. “Our purpose is not to punish everybody. Our purpose is to correct some unsafe conditions,” he said.

That cooperative spirit was evident when a participant asked what to do with cyanide, which is in numerous jewelry-district buildings but will be prohibited by the guidelines. “I would highly recommend you use it up,” said city Fire Department Inspector Tobi Perkins. Not all participants at the meeting were pleased with the guidelines. Ronald Hartmann, a lawyer for a jewelry manufacturer concerned about what he considers hazardous conditions in the district, said he was upset that the task force met privately. (A manufacturers’ flier promoting the meeting said it was “closed to the public,” despite the presence of local, state and federal officials; a Times reporter who attended was asked not to participate in the question-and-answer segment of the program.)

“In a state that prides itself on sunshine for government, it looks like a covert attempt to make something illegal legal,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.