Listening Is a Gift of the Here and Now

- Share via

Me: Yack yack, yadda yadda....

She: Oh? Hmmm....

Me: Yes and more, thus and so....

She: Hmmm....

I had dinner recently with a listener. A superb listener. A listener who thinks listening is so important that she is writing a book on this old and--as I came to learn--increasingly rusty social skill.

Ahhhh....

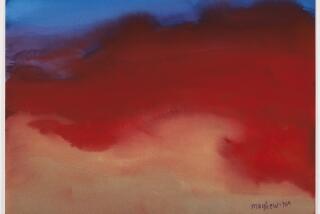

We were outside on a restaurant patio, California midwinter. Our mealtime topic of conversation: listening, of course.

“It is so precious to be listened to. It’s surely a gift. I’m so astonished what listening can do for people,” says my guest, Irene Borger. “It’s very primal. It’s very visceral. It’s very intimate.”

To be honest, I cannot remember the last time I gave thought to the subject of listening. I don’t recall whether I regarded it even as a subject, instead of just something one takes for granted. I started listening in the crib, maybe sooner. And it’s how I’ve made my living for 31 years. What is there to it?

Then I had a chance introduction to Borger, who is director of an 8-year-old program to recognize excellence in the visual and performing arts, the CalArts/Alpert Award in the Arts, and former artist in residence at AIDS Project Los Angeles. She is the editor of the book, “The Force of Curiosity.” She is also the best listener I’ve ever listened to.

She is the unusual kind of person who will say this: “I’d be happy to use my 15 minutes of fame listening.”

For days now, I’ve been dwelling on her ideas. I think it’s no overstatement to confess that by heightening my appreciation of the obvious, she altered my self-awareness by a few degrees. I haven’t been such a good listener after all. It has cost me, I see, both in the pleasure of listening and the respect that listeners command.

If I can generalize for effect, I might say the same about you. I haven’t been around many good listeners lately.

“There is a difference between listening and hearing,” Borger observes. “Listening is volition. It’s active. It’s engaged. Listening is a transaction.”

I’ve been thinking about those everyday conversations people have in which everyone seems to be talking or winding up. I’ve been observing encounters between couples, between adults and children, between public officials and the public, between managers and employees. I see afresh the many cues that signal, “I’m hearing you but I’m not listening.”

Borger and I came up with a theory. I say “we” because that is the secret of being around a good listener. Somehow, you feel part of the action. The theory is this: Listening is about being in the present. Those of us in busy urban environments spend too much time looking over our shoulders. Our thoughts leap ahead to tomorrow’s obligations. It is the habit of our work, and it slops over to our conversation. As we lose our grasp on the present, our busy brains forget to listen.

I think back on our dinner. Listening is a form of concentration. But it’s unlike the concentration required in talking. Because I was attentive to the moment, I have a keener memory of my surroundings, the richness of the risotto, the thinness of the wine, the background city sounds.

“You see, listening is witnessing,” says Borger.

As we listened, Borger and I came up with a dozen ideas. The point was that just listening about listening opens up discoveries as unexpected as if you suddenly found that you were double-jointed and could scratch your nose with a toe.

“We usually think of a person who is speaking as the one who is in control,” says Borger. “But that’s false.”

She surprises me, but she’s correct. We all have highly developed filters against the irritation of the bore and the steady assaults of the wheedlers. Ultimately, the power belongs to the listener, by the choice of what passes through. Great listeners, like the late socialite and ambassador Pamela Harriman, have the gift of making important people feel worthy and thus became powerful themselves.

Dinner is ending. Borger has one more story. How did she learn to listen? Her father’s parents were deaf and spoke with sign language. Their knowledge was passed along to her. It takes more than ears to listen. It requires your eyes, hands, face, the nod of the head, the bite of a lip--many elements to the transaction. Borger’s fascination for listening goes back to conversations of silence.