Vereen Revisits Broadway a Wiser but Joyful Man

- Share via

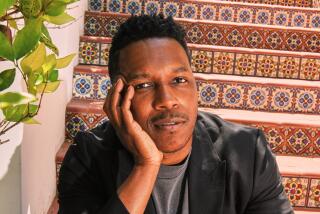

NEW YORK — On one side stands the mighty Brooklyn Bridge. On the other, the Manhattan Bridge. In between stands Ben Vereen, looking every bit as vital as the mammoth girders that loom above him.

It is morning in Brooklyn, and Vereen can’t wait to follow one of these two hulking spans into Manhattan and then Broadway, where the Tony-winning song-and-dance man has always gravitated like a moth to light.

“I have a rehearsal today,” he says. “You know what’s a good feeling? When you wake up in the morning and you go, ‘I have a place to go! It’s called a theater and I have a job!’ ”

There is a good reason for such glee: Vereen just marked the 10th anniversary of an auto accident that left him with serious head and internal injuries that required four hours of surgery. Few expected him to walk again, much less perform.

“I have problems,” he says. “I have taxes and bills and things with relationships that I have to go through. But thank God that I’m waking up today to deal with it.”

This month, Vereen reprises the role of retired boxer Midge Carter in a revival of “I’m Not Rappaport,” the drama of two older men coming to grips with their lives and infirmities.

Much has changed for Vereen since he first tackled the role in the late 1980s. This time, he has infused the past with what he learned from his own agonizing years of rehabilitation.

“I draw on the frailty and the aging process,” says Vereen, 55, who is paired with Judd Hirsch. “Midge has got his angst. He’s weaker than he was in his prime. I know about that stuff. That applies to me.”

Vereen in real life betrays little of such angst and ill health. Though his beard is flecked with gray, he laughs heartily and moves as gracefully as he did in such musicals as “Hair,” “Jesus Christ Superstar” and “Pippin.”

Vereen’s new home is in one of the hottest areas of Brooklyn, the borough where he was raised. It’s a neighborhood of former factories and warehouses that is affectionately known as DUMBO--Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass.

Ten years ago, nobody came to these rough streets. Now Civil War-era buildings are slated to become malls or are being converted into lofts. Vereen lives in a former paper factory that is dotted with chic apartments. “If the element of good comes, the element of bad has to leave,” he says.

That might as well be Vereen’s motto. Despite heartache in his life that includes the loss of a daughter, his faith remains intact.

“I do believe in prayer. I do believe in a higher power. And I do believe in God, Allah, Buddha, Jesus, whomever you decide to call the divinity. The power of that is within us all and if we allow it, it can restore us.”

That faith also has propelled Vereen to donate his time to everything from helping drug addicts to stopping sudden infant death syndrome to fighting heart disease to boosting inner-city arts.

Vereen’s 30-year-old daughter, Malaika, says she has seen her dad bounce back from turbulent times while retaining his desire to help others. “My father has so much strength and love in him and that’s really the hardest part: He really feels for people and it’s in his soul,” she says. Then she adds with a note of anxiety, “It concerns me that it’s in his soul.”

Vereen left Brooklyn for the first time when he attended the High School for the Performing Arts in Manhattan in the early 1960s. Enough people saw talent in the cocky gang member to push him over the bridge.

Later, during an audition for the musical “Sweet Charity,” Vereen caught the attention of legendary choreographer Bob Fosse, who would play an important part in the young dancer’s life.

Vereen won roles in “Pippin,” “Hair,” “Jesus Christ Superstar” and, later, “Grind” and appeared in such movies as “All That Jazz.” On television, he co-starred in TV’s landmark series “Roots” and had a recurring role in the 1990s police show “Silk Stalkings.” His 1978 network special, “Ben Vereen: His Roots,” won six Emmys.

However, a cocaine addiction kicked in as his fortunes rose. In 1987, tragedy struck as his 16-year-old daughter, Naja, was killed when the family van was crushed by a tractor-trailer.

“I lost a lot of things in those days during the drug period, a lot of personal things. The most important thing was time--time I could have spent with my children,” he says. “I could have spent more valuable time with her.”

Five years later, in June 1992, Vereen’s life was threatened when he crashed his Corvette into a tree near his home in Malibu. Later that day, he was struck by an SUV and thrown 130 feet while walking along Pacific Coast Highway.

“When I was laying there in bed, the doctor said I’d never walk, I’d never dance again, I’d never sing again,” he recalls. “Every night when I couldn’t sleep, I’d sit there in prayer. I’d sit there and meditate on my body.”

By sheer force of will, he healed. Only 10 months later, Vereen made a triumphant return to Broadway in “Jelly’s Last Jam,” opposite Gregory Hines. Then he did the demanding “Fosse.”

Vereen has become fast friends with the man who hit him, Grammy-winning music producer David Foster.

“I had met him three years before and I had said, ‘We should get together,’ ” Vereen says with a sly smile. “A phone call would have been nice.”

Says Malaika about the crash, “He looks at it truly as a blessing. He had had a stroke earlier that evening and he thinks that was an intervention to save his life. A lot of people wouldn’t see it that way.”

Her father soon became sober--and spoke up about his experience, founding Celebrities for a Drug-Free America, a nonprofit group dedicated to educating youngsters about the dangers of drugs.

“I had a lot of problems after that. The industry said, ‘We can’t associate with someone like this.’ But I had to tell my story and take whatever the consequences were. I’m not using today and that’s the important thing. I’m not that dark creature I was before.”

With that, Vereen rises to prepare for his trip across the bridge and into Manhattan. His outlook could be summed up by the concluding words in his biography for the “I’m Not Rappaport” Playbill.

“As always, this performance is dedicated to my daughter Naja,” Vereen writes. “Life is good.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.