Peru Ruins May Be Civilization’s Cradle in the Americas

- Share via

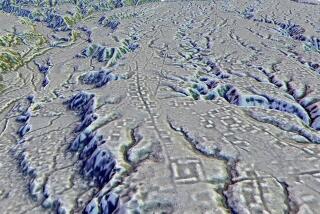

CARAL, Peru — In a barren landscape that now looks like the moon, a mysterious culture built pyramids here nearly 5,000 years ago. Until recently, few archeologists would have believed that.

The pyramids, apparently temples, loomed over sunken plazas and an amphitheater. Neighborhoods were scattered among them, split into rich and poor. An irrigated river nourished fields of cotton and squash that were traded with faraway cultures.

In short, a city thrived here, something that was not thought to have happened in this hemisphere until 1,500 years later.

“The evidence of Caral puts into question what had been accepted until now,” said Ruth Shady, a Peruvian archeologist from Lima’s San Marcos University who has led excavation of the site.

“The splendor of Caral--2,600 years before Christ--is contemporary to the splendor of the Egyptian pyramids, the pyramids at Giza and the cities in Mesopotamia.”

Since 1994, Shady and a team of archeologists have sifted through dune-like mounds on this desert plateau overlooking the Supe River valley 90 miles northwest of Lima, in what could be the cradle of civilization in the Americas.

The archeologists knew early on that they were unearthing a city. But they could not find ceramics or pottery, suggesting that it was built when ancient Americans were still thought to live in decentralized rural societies.

Shady proposed that Caral predated Mayan settlements in Mexico and Central America by centuries, a claim she said her colleagues greeted with disbelief until last April.

That was when she and two American researchers published hard proof in the journal Science. The Americans--Jonathan Haas of Chicago’s Field Museum and Winifred Creamer of Northern Illinois University--had carbon-dated material from Caral’s main pyramid to as far back as 2627 B.C. Shady said people began settling the city around 2900 B.C. and it was continuously inhabited for 1,000 years.

During Caral’s heyday, many of its 3,000 residents most likely filled the 100-foot-diameter amphitheater for religious ceremonies led by high priests playing flutes made of pelican and condor bones.

The pyramids gleamed yellow, white or brick red in the setting sun as the inhabitants feasted on fish caught in the Pacific Ocean or on vizcacha, a rodent that was hunted in nearby shrub lands.

When the day was done, the townspeople retired to home: the priests and their servants to stone-block complexes near the pyramids, the commoners to smaller mud-thatch huts outside the town center.

Shady believes that Caral was a sacred city and administrative center for a civilization that built 17 other sites, most still buried in the Supe Valley and on the nearby Pacific coast. She chose to excavate Caral first because its layout appeared the most sophisticated.

Six pyramids dominated its skyline, covered for centuries after the city’s abandonment by wind-whipped sand and blending in with the rocky hills that ring the site.

The largest stood about 60 feet high, rising in terraced platforms from a base about the size of four football fields. A circular stone plaza sat at the foot, fronted by porticoes made of boulders as large as refrigerators. The pyramid is the largest found yet in Peru, Shady said.

Archeologists believe that the large rocks were dragged from nearby quarries with ropes woven from reeds. Net sacks were used to lug groups of smaller rocks and later dumped, bag and all, to fill foundations.

Shady’s team has found evidence that the entire city, including the paved plaza floors, was painted one color with natural dyes. The color changed over time, though it is unclear why. Traces of red paint are still visible on the main pyramid.

Although the Caral inhabitants did not mold pottery or fire ceramics--or develop writing--they apparently composed music.

The site’s showcase artifacts are 32 flutes made from animal bones and engraved with figures of birds and monkeys, a sign that the makers may have ventured over the Andes mountains and into the Amazon jungle. The instruments were found near a fire altar attached to the amphitheater, suggesting that public ceremonies were carried out there.

Caral subsisted on crops and small game hunted in surrounding vegetation, which grew in a climate that was more humid than today’s desert weather. Remains of seeds, fish bones and seashells suggest Caral traded with fishermen on the coast 12 miles to the west and with people from as far away as Ecuador.

Although it is easy to imagine life at Caral with the guidance of archeologists, the site itself is still only crudely reconstructed, appearing mostly as piles of rocks and rubble.

Shady has begun the task of persuading Peru and the world to help conserve what has been called the most important archeological find here since Machu Picchu, the Incan citadel discovered in 1911.

That meticulously restored Incan citadel, discovered in a jungle-shrouded valley in southern Cuzco province, has become Peru’s main tourist attraction and a national symbol.

Caral is a long way off from such status. Erosion, neglect and looting threaten the site, Shady said. It is still difficult to reach, connected to the main coastal highway by a rutted dirt road. Peru’s cash-strapped government has allotted San Marcos University some $500,000 for preservation, but Shady hopes to raise much more from foreign donors.

“Caral’s architecture needs to be conserved so it can be shown to Peru and to the world,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.