Discovery Brings Hope to Sufferers of Harsh Digestive Disorder

- Share via

Scientists say they have pinpointed the cause of a common, debilitating disease of the gut that affects more than a million Americans, a finding that could lead to the first effective therapy for the disorder.

People with celiac disease--also known as celiac sprue or gluten-sensitive enteropathy--cannot eat foods containing wheat, rye or barley. If they do, they face severe discomfort, vomiting, diarrhea, malnutrition and even death. A new therapy could allow victims to lead a much more normal life.

Researchers at Stanford University and the University of Oslo in Norway report in today’s Science that they found a small protein fragment in the cereal grains that triggers an immune reaction in celiac patients. The fragment is a portion of a protein known as gluten.

Though most proteins are quickly chopped up by digestive juices, this gluten fragment persists--permitting inflammation to develop in the guts of susceptible people. They found that the fragment is not present in grains that can be consumed safely by celiac patients.

The team also identified a bacterial enzyme that can chop up the protein, offering the promise that a pill might one day be developed to prevent celiac symptoms.

This might allow celiac patients to eat at least some gluten-containing items, much as a person with intolerance to the milk sugar lactose can now swallow a lactose-digesting pill to consume an ice cream cone.

“If it does work ... it could be a very rapid and effective therapy,” said Dr. Damian Augustyn, chief of gastroenterology and hepatology at California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco. “Gluten is present in so many food products, and patients have to be so careful to exclude it. Inevitably they’re not 100% successful.”

But Augustyn and other experts caution that the idea of an oral supplement, while intriguing, faces many tests before its promise can be assessed.

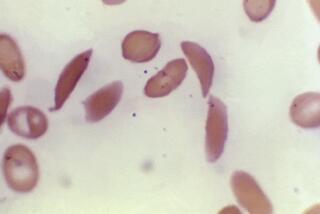

Celiac disease is a poorly understood genetically linked condition in which the patient’s immune system attacks the small intestine when it is exposed to gluten. The result is inflammation and a progressive loss of the tiny brushlike folds that allow food to be efficiently absorbed.

Typically diagnosed in children, it is increasingly being diagnosed in adults. The ailment can lead to anemia and loss of bone mass, and even a slightly heightened risk of certain cancers, if untreated.

Frequently, it can take months or years for a correct diagnosis to be made. Once identified, the only treatment is the strict avoidance of dietary gluten--by eschewing all products containing wheat, barley and rye.

The connection with gluten was first recognized in the 1940s, when a Dutch pediatrician noticed that children with the illness fared better under wartime rations, when cereal supplies were short--only to relapse when grains were reintroduced. The disorder was subsequently found to be genetic, and researchers have linked some gene variants to it.

In today’s paper, Stanford chemist Chaitan Khosla and his colleagues bathed various pieces of gluten protein in human digestive juices and found that one fragment, just 33 amino acids long, persisted for many hours while the other pieces were destroyed. Rats were also unable to digest it.

The fragment was also shown to activate immune cells in the guts of 14 patients with celiac sprue, a key step in producing disease symptoms.

Developing an oral supplement that could digest this fragment could make the lives of people with celiac disease much easier, said Khosla, whose wife and 6-year-old son suffer from the ailment.

“This is not some kind of boutique disorder--nor is it a minor nuisance,” he said. “The burden of disease is truly enormous on a patient.”

Celiac patients must avoid many more foods than the obvious breads and pastas. Gluten can be present in everything from soy sauce and seasoned salt to turkey meat, cottage cheese and soups.

Khosla and colleagues are planning a small trial in which healthy adult patients with the ailment will be given the enzyme--known as a peptidase--to see if it improves their gluten tolerance.

If that works, said Khosla, many more steps would be needed before a pill could be developed. For instance, it would have to be tested for safety and its ability to survive sufficiently long in the gut.

“I think it’d be cool. It would be nice to eat normal bread and pizza and not have to question everything,” said Bay Area resident Molly Duncan Stone, 12, who was diagnosed with celiac disease as a toddler after she stopped walking, talking and playing and began losing weight precipitously.

Now thriving on a gluten-free diet, she has learned to read labels, bake her own pizza and cookies to take to birthday parties, and was pleased to receive a gluten-free cookbook as a Christmas present.

Recently, dining with friends, all she dared eat was an egg.

Today’s paper represents a key step forward in understanding celiac disease, said Dr. Martin Kagnoff, professor of medicine and director of the laboratory of mucosal immunology at UC San Diego. But many mysteries remain.

For instance, Kagnoff said, although celiac disease is associated with a certain gene, only 2 of 100 people carrying that gene get the disease. “The other 98% don’t--and the question is why.”