Acquirers Desire ‘Secret’ Workers

- Share via

Over the years, Conquest Inc. has generated about as much revenue annually as Boeing Co. does in a few hours.

So why would the Chicago aerospace giant, with about 170,000 employees, be interested in buying an obscure firm with a staff of 200?

The answer: Conquest gave Boeing something that is a precious commodity in the defense industry these days -- workers with top security clearances.

“Ninety-nine percent of Conquest’s employees have special-access clearance,” explained Greg Jones, deputy general manager of Boeing’s space intelligence systems, who oversaw this year’s purchase of Conquest.

Boeing refused to divulge Conquest’s largest customer. But industry sources say the Annapolis Junction, Md.-based firm recently won a $140-million contract for a project dubbed “Trailblazer,” a National Security Agency program to upgrade its eavesdropping on military communications overseas.

The deal is part of a trend by the nation’s largest defense contractors, which have been quietly on the prowl for “body shops,” or privately held enterprises that often work on classified programs and are loaded with employees who possess highly coveted government security clearances.

Clients typically include the CIA, the NSA and the FBI -- all of which often require contractors to use employees who have passed rigorous background checks. With the exception of those clearances tied to the nation’s most sensitive programs, most workers can take their security clearances with them even if they change employers.

Since the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, at least 16 small intelligence firms have been acquired as the nation’s biggest Pentagon contractors ready for a dramatic increase in federal spending on military programs and homeland security. Defense spending on research and development -- which funds many classified programs -- rose 20% to $56.8 billion this year, and is expected to rise steadily for the next five years.

Many lucrative intelligence contracts are likely to be awarded quickly, and companies can’t afford to wait for their employees to work through the bureaucracy and obtain the type of government clearances required to compete for those contracts.

Indeed, since the terrorist attacks, there has been a bottleneck in getting new clearances. The Pentagon’s Defense Security Services conducts the investigations and necessary background checks, and though the logjam has lessened recently, some high-level clearances still can take 18 months.

Thus, the bidding war for small intelligence firms.

Boeing officials acknowledge that Conquest gives them access to the close-knit intelligence community. Boeing, which started as a commercial aircraft maker, has diversified into defense work and is hoping to boost its contracts for “network centric” warfare. This system, in which disparate computers are linked instantly, is designed to give top military planners a comprehensive view of what’s happening on the battlefield.

Conquest “has tremendous customer relationships in areas where Boeing didn’t have strong relationships,” Jones said.

This month, General Dynamics Corp., the maker of tanks and nuclear submarines, entered the intelligence-buying spree by acquiring Herndon, Va.-based Creative Technologies for an undisclosed amount. And last fall, BAE Systems North America, the nation’s fifth-largest defense firm, bought 100-employee Corbett Technologies in Alexandria, Va., for $15 million. Both firms develop sophisticated computer software for intelligence agencies.

Most of these deals have garnered little attention on Wall Street, falling below the radar of analysts because the purchases are small -- ranging from $2 million to $100 million.

“You don’t hear about them in the traditional mergers and acquisitions community,” said Richard Phillips, vice president of the aerospace and defense group for investment bank Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin.

These small intelligence firms keep a low profile. Most are not listed with business information provider D&B; Corp., formerly known as Dun & Bradstreet, and typically don’t have publicly accessible Web sites. The companies also are reluctant to say anything that would compromise their business with secretive intelligence agencies.

In many cases, these firms were started by former government officials. BAE’s Corbett, for instance, was founded by a former Navy officer who oversaw security for the Pentagon’s key command and control facilities.

“They get their foot in the door to the intelligence community, which is tough to crack for outsiders,” said Edward H. Kim, a government contracts lawyer for Whiteford, Taylor & Preston, which has handled some of the recent sales. “They’re covering positions in areas that could be very powerful in the aftermath of Sept. 11.”

According to analysts, classified intelligence work generates profit margins of 10% to 12%, double the earnings of traditional defense businesses. As a result, competition for these firms has driven up the price tags, with some of the more coveted companies fetching 80% to 100% of their annual revenues.

In February, ManTech International Corp. bought a Virginia firm, Integrated Data Systems, for $57 million, or 126% of its annual revenue, Houlihan Lokey said. Integrated Data Systems develops specialized software for the Defense Intelligence Agency and the CIA.

“Some of the highest-value companies are those that serve the intelligence agencies,” Phillips said.

Workers at these firms have different layers of security clearances, ranging from “confidential,” the easiest to obtain, to “top secret,” the classification typically required to work on intelligence and national security programs. Within the top-secret category there are several subsets, and some require extensive background checks that may include FBI agents interviewing relatives and neighbors, reviewing tax returns, scouring credit reports and administering polygraph tests.

When General Dynamics acquired Creative Technologies, the defense contractor declined to say exactly what Creative did or who was the firm’s main customer. But Creative supplied “300 employees with high-level security clearance,” said Kendall Pease, a General Dynamics spokesman. “They come with instant workers who have the expertise we want, and provide the added benefit of having people with clearance.”

These companies also are attractive because their plants have government clearances, which require all sorts of costly security measures.

“To get a facility clearance and classified personnel takes significant investment and time,” said Ross K. Anderson, a director at Newport Beach-based investment bank Janes Capital Partners, who previously ran a classified defense firm in Tustin.

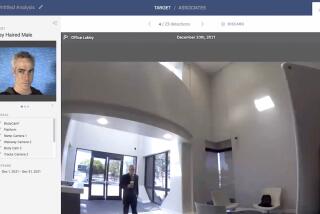

Buildings for intelligence firms have to be constructed or modified with special double doors armed with electronic locks, alarms with heat sensors and video cameras. And they must be maintained by a security staff whose backgrounds have been checked by the Pentagon, Anderson said. Even janitors at the buildings require special government clearance.

“The overhead associated with that,” he said, “is not trifling.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.