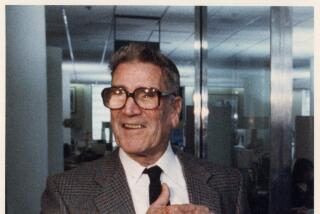

John ‘Tex’ McCrary, 93; Radio, TV Pioneer Urged Voters to Like Ike

- Share via

John Reagan “Tex” McCrary, a radio and television host and a publicist who masterminded the political rally that helped launch Dwight D. Eisenhower’s presidential campaign in 1952, died Tuesday in New York City. He was 93.

With his wife, the actress and model Jinx Falkenburg, McCrary pioneered talk radio programming with the morning show “Hi Jinx” in 1946. The next year the popular couple branched out to television with “At Home.” From then on, they alternated between the two, using the same basic format for both. Their shows combined news, celebrity interviews and household tips.

Born in Calvert, Texas, McCrary was the grandson of U.S. Sen. John H. Reagan. McCrary graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale University with a degree in architecture before he decided on a career in journalism. He began his newspaper career at the New York World-Telegram in 1932.

He went on to become the chief editorial writer for the Mirror, a New York daily, and married Sara Brisbane, daughter of the paper’s editor, Arthur Brisbane, in 1935. The couple divorced four years later.

During World War II, McCrary worked as an Army Air Forces photographer and publicist in the Mediterranean, rousing U.S. public opinion in favor of strategic bombing in that region.

McCrary met Falkenburg in 1941 when he interviewed her for a column he wrote for the Mirror. She had a role in a Broadway musical, “Hold on to Your Hats.” They met again during the war when she was on tour with the USO, entertaining troops overseas. The couple married in June 1945.

That year, McCrary was among the first Americans to visit Hiroshima after the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on the city. He advised journalists not to report on Hiroshima because Americans would be shocked by reports on the damage incurred. Journalist John Hersey wrote a full description of the bombing and the effects for the New Yorker magazine. It was made into a book in 1946.

Years later McCrary said of the bombing: “I covered it up and John Hersey uncovered it. That’s the difference between a PR man and a reporter.”

In 1949, after he completed his military service and had become a media personality, McCrary was commended by the Air Force for his role as an exceptional civilian who inspired quality young men to serve in the military. Three years later, he helped convince Eisenhower, who was serving in Paris as commander of NATO, that he had voters’ support and should run for president as a Republican.

At a rally in Madison Square Garden, headed by McCrary, Broadway idols Ethel Merman and Mary Martin performed to a crowd of at least 18,000. McCrary helped lead the chant, “We like Ike.” Several weeks later, Eisenhower declared his candidacy. McCrary took a leave of absence from television to help get him elected in 1952.

One of McCrary’s most successful public relations efforts came years later in Moscow, when he produced a display for the 1959 American National Exhibition. The model of the typical American kitchen became the backdrop for the “kitchen debate” between visiting Vice President Richard M. Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev.

Pictures of the encounter captured Nixon, who would soon be running for president, poking his finger into the chest of the Soviet leader, the subtext being that in the Cold War, Nixon would stand up to the Communist menace.

Later in his career, McCrary worked as a public relations consultant with clients ranging from Learjet to the government of Argentina. He supported Nixon in the early days of Watergate and later campaigned for Republican candidate Ronald Reagan in 1980. He tried to convince Gen. Colin Powell to run for the office in 1996, comparing him to Eisenhower for his leadership abilities. Powell decided against running.

McCrary and his wife separated after many years of marriage but never divorced. He is survived by her, their sons Kevin and John, and Michael, his son from his first marriage.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.