A Somber Bush Leads a Nation in Grieving

- Share via

WASHINGTON — It was 9 a.m. Saturday at Camp David, the placid presidential retreat in the mountains of western Maryland. President Bush had just finished an intelligence briefing and was looking forward to relaxing with his wife, Laura. In a nearby guest cabin, his chief of staff, Andrew H. Card Jr., was idly channel surfing.

Live coverage of the space shuttle Columbia’s landing caught his attention. Card watched as the shuttle passed over Texas, and then as the signal was lost.

Even as NASA scrambled to locate Columbia, Card sensed that something was wrong. He telephoned the White House Situation Room. He tried to call NASA, but didn’t get through. He decided not to dawdle.

By the time the shuttle was supposed to have landed at 9:16 a.m., Card had already burst in on the president’s idyll and delivered the bad news.

Bush’s immediate response was to express “deep concern for those on board and especially for their families,” said deputy White House spokesman Scott McClellan.

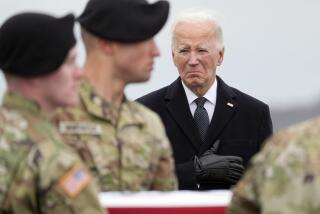

From then on, not only was Bush commander in chief, he was the chief mourner.

He dispatched National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, who also was at Camp David, to command the White House Situation Room. He put in a call to NASA chief Sean O’Keefe. The Secret Service scrambled to assemble a motorcade so the president could return to Washington; heavy fog in the nation’s capital prevented a safer, speedier helicopter ride.

And perhaps most important, White House speechwriters were told to get to work. The president needed to call the nation to grief and offer what he could in the way of comfort.

Bush arrived at the White House at 12:20 p.m. in an armored Chevy Suburban. He was in the Oval Office 10 minutes later and reviewed the first draft of his speech. His priorities, he told aides, were to express sympathy for the families and dedication to the space program, and to provide comfort to the nation. He suggested a few changes.

At 12:45 p.m., he picked up the phone to make his most difficult call of the day.

At the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where they had gathered to welcome their loved ones home, astronauts’ family members instead held hands and gathered around a speakerphone in a conference room.

“I want to express our love and appreciation for all who died today,” Bush told them. “I want the loved ones to know there are millions of Americans praying for you.” Two of them, he said, were himself and his wife.

“I wish I was there to hug and comfort and cry with you right now,” the president said. “God bless you all. God bless.”

Bush hung up and stepped into his private study, apparently to compose himself, leaving a handful of aides standing respectfully in silence.

When he returned a few minutes later, he went into the West Wing’s Roosevelt Room for a briefing with Rice, Secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge and John Marburger, director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. He signed a proclamation ordering all flags at federal facilities in the United States and abroad lowered to half-staff, and flags on all naval vessels to half-mast, through Wednesday. The flag over the White House was the first.

By 1:30 p.m., Bush had returned to the White House residence to make a series of telephone calls.

The first was to Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, to whom he expressed deepest condolences over the death of Ilan Ramon, an Israeli Air Force hero who was the first person from that country to fly into space. Sharon, in turn, expressed his sympathies for the loss of the Columbia crew.

Bush also returned calls from other leaders: Mexican President Vicente Fox, over whose territory some space shuttle debris may have fallen; French President Jacques Chirac; and Russian President Vladimir V. Putin. Bush and Putin pledged to work together as their countries deal with the aftermath of the accident, which complicates their joint work on the international space station. Bush told Putin that despite the accident, space exploration remains a priority for the United States.

It was nearly time for the president to address the nation; while in the White House residence, Bush had changed his clothes, returning to the Oval Office in a somber, dark blue suit and a blue and white tie. He reviewed the text prepared by his speechwriters and made some changes. He spoke briefly to Karen Hughes, his former aide and informal political advisor, who suggested that he add a Bible verse from the Old Testament book of Isaiah. And a few minutes after 2 p.m., he walked the few feet from the Oval Office to the Cabinet Room and stepped up to a lectern hastily set up in front of the fireplace.

The president looked into the TV cameras: “The Columbia is lost. There are no survivors.”

*

Times staff writer Ronald Brownstein contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.